Abstract

Purpose

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is associated with variable risks of extracutaneous manifestations and death. Currently, there is limited information on the clinical course and prognosis of EB in Korea. This study analyzed the nutritional outcomes, clinical morbidity, and mortality of children with EB.

Materials and Methods

Thirty patients, admitted to Severance Hospital and Gangnam Severance Hospital, from January 2001 to December 2011, were retrospectively enrolled. All patients were diagnosed with EB classified by dermatologists.

Results

Among the 30 patients, 5 patients were diagnosed with EB simplex, four with junctional EB, and 21 with dystrophic EB. Wound infection occurred in 47% of the patients, and blood culture-proven sepsis was noted in 10% of the patients. Two (9.2%) patients had esophageal stricture and 11 (52.4%) of the dystrophic EB patients received reconstructive surgery due to distal extremity contracture. There were five mortalities caused by sepsis, failure to thrive, and severe metabolic acidosis with dehydration. According to nutrition and growth status, most of the infants (97%) were born as appropriate for gestational age. However, at last follow-up, 56% of the children were below the 3rd percentile in weight, and 50% were below the 3rd percentile in weight for height. Sixty percent of the children had a thrive index below -3.

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB), inherited as an autosomal dominant or recessive disorder, is characterized by blister formation and erosion of the skin and mucous membranes with minor trauma.1 Based on histologic involvement, there are three major EB classifications: EB simplex (EBS), junctional EB (JEB), and dystrophic EB (EBD).2,3 EB simplex occurs within basal keratinocytes, and shows the mildest clinical manifestations. JEB involves the lamina lucida; the Herlitz subtype of JEB causes the most severe phenotype, consisting of intractable erosion blisters, and progresses to an early death due to infection. Dystrophic EB occurs in the dermis and manifests as blistering, scarring, and milia formation.3,4

According to the US national EB registry, the estimated prevalence of EB in the United States was 8.22 per 1 million individuals in 2008.5 The Australian registry reported an estimated prevalence rate of 10.3 cases per million in 2009.6 The epidemiology of EB in Korea has not been reported; only one study reported a prevalence of about 68 EB cases in 1993.7

Because multiple organ system involvement occurs early in EB patients, clinicians should carefully evaluate conditions such as dental manifestations, gastrointestinal tract involvement, infection, and musculoskeletal problems.3,8 Severe failure to thrive, as a consequence of restricted nutritional intake, and chronic constipation have been reported as the main causes of death in EB patients.8,9 Therefore, aggressive nutritional support to prevent growth failure, nutritional deficiencies, and compromised immunity may affect disease outcome. Unfortunately, information concerning the clinical course and prognosis of EB is very limited in Korea. Accordingly, this study was designed to analyze the nutritional outcomes, clinical morbidity, and mortality of children with EB in Korea.

We retrospectively analyzed 38 patients with EB. The patients were diagnosed by dermatologists at Severance Hospital and Gangnam Severance Hospital using immunofluorescence, mapping, and transmission electron microscopy from January 2001 to December 2011. Eight patients were excluded because of a lack of information. Data concerning height and weight at birth and at the last follow-up (median 60.5, range 1-224 month) were collected, and each patient's percentile in growth was determined. We designated nutritional indices as weight, weight for height, and thrive index. Percentile of weight and weight for height were calculated based on the 2007 Korean national growth charts.10 The thrive index was calculated based on the same growth standards, using the following formula: weight standard deviation-(birth weight standard deviation×0.4).10,11 We also collected histologic classification, clinical history, and laboratory findings for each patient. Medical records as well as inpatient and outpatient charts, laboratory results, pathology results, and skeletal radiographs of all affected patients were reviewed.

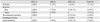

Among 30 cases of EB, 17 cases (57%) were male and 13 cases (43%) were female. All of the patients showed skin symptoms at birth. Subtype analysis identified 5 cases of EBS (17%), 4 cases of JEB (13%), and 21 cases of EBD (70%). All were born at term gestation. Twenty-nine (97%) of the patients were appropriate for gestational age; one case of EB simplex was small for gestational age. Among EBS, EBD, and JEB groups, there were no significant differences in gestation and birth weight (p=0.35, p=0.09) (Table 1).

Nutritional status based on growth parameters is shown in Table 2. At last follow-up, fifty-six percent of the patients were below the 3rd percentile in weight. In regards to weight for height, 50% were below the 3rd percentile. Among the EBS, JEB, and EBD patients, the proportions of patients below the 3rd percentile in weight and weight for height were not different between the subgroups. Eighteen patients (60%) were below -3 on the thrive index. There was no significant difference in the number of those below -3 on the thrive index among EB subtypes. The most recent follow-up indicated that most of the patients were below the 3rd percentile in weight, weight for height, and thrive index, reflecting a failure to thrive (Table 2).

Serum albumin (median 2.7 g/dL range 1.8-3.5 g/dL) and serum protein (median 5.9 g/dL, range 4.8-7.0 g/dL) levels were recorded as their lowest values. Ten (33%) patients demonstrated a hypoalbuminemia event (<2.5 g/dL) during evaluation; all mortality cases-showed marked hypoalbuminemia. The median cholesterol level was 148 mg/dL and ranged from 120-187 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels did not reveal any specific findings. Serum protein, albumin, and cholesterol levels tended to be at the lower margin of normal values.

According to morbidity and mortality survey, there were five patient deaths. The median age at time of death was 7.3 months (15 day-22 month). Three deaths (60%) were noted in children with JEB, one with EBS, and another with EBD. A mortality rate of up to 75% was noted in patients with JEB. The causes of death included failure to thrive in 2 cases, sepsis in 2 cases, and severe acidosis with dehydration in one case. Among mortality cases, 4 patients were below the 3rd percentile of weight and weight for height, and one was below the 5th percentile of weight and weight for height at the time of death. A skin wound site and blood culture were performed. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was confirmed as the primary cultured organism at the wound site. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus hominis, and candida were cultured in the blood. Twelve patients underwent reconstructive plastic surgery operations for leg and hand contracture, and 11 of the patients had EBD. Two patients with EBD experienced esophageal stricture treated with esophageal ballooning, and all of the patients required dental care to address gum problems (Table 3).

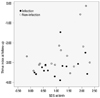

Weight SD scores at birth and thrive index scores at last follow-up are shown in Fig. 1, and reflect overall growth failure in EB patients. Especially, across the whole range of birth weights, patients identified with infections tended to show lower thrive index scores at last follow-up, compared to the patients noninfected patients, reflecting severe growth failure; nevertheless, this was not statistically different (p=0.08).

The present study is the first in Korea to investigate detailed growth and nutritional outcomes in children with EB. Previously, only one report has assessed the risks of complications related to EB in Korea. Little information is available regarding the natural history and nutritional analysis of each major EB subtype in Korea.

EB is an inherited mechanobullous disorder characterized by skin fragility and blister formation.12 To date, over 1000 different mutations involving 14 structural genes within the skin have been shown to be associated with EB clinical phenotype.5,13 EB is associated with many clinically distinctive phenotypes, all of which consist of skin blistering as a major feature, which may vary in regards to the degree of extracutaneous manifestations and death.5 Previously, manifestations of external eye erosion, esophageal stricture, intestinal malabsorption, hydronephrosis, and chronic renal failure have been reported. Additionally, severe complications in the musculoskeletal system, heart, bone marrow, and oral cavity (enamel hypoplasia, microstomia, and ankyloglossia) have been reported to contribute to morbidity and even death.

The prevalence of EB has not yet been reported in Korea. In 1986 the National Institutes of Health established the National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry to determine the risk of extracutaneous outcomes.8 Over 16 years, 3280 patients throughout the United States were enrolled and evaluated. The Australian Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry was established in 2006, and has continued to increase in size and profile locally. In the United Kingdom, 2930 patients have been enrolled for over 16 years of follow up with the National EB Registry since 1993.6

In the past, infant mortality from infection was a major concern due to the unavailability of sophisticated wound care products, the lack of burn unit technique applications, and the absence or incorrect use of broad-spectrum topical and systemic antibiotics.14 Over the past 20 years, however, various synthetic dressings have been developed and are used extensively in daily care for patients with EB. In our study, although 40% of the patients developed skin infections, only 10% of the cases involved blood culture-proven sepsis.

In general, infant mortality reports of sepsis by the age of 1 year have ranged from 0.4% to 19.5%. By age 15, the cumulative risk of death from sepsis increased to 24.2% for EB patients.15 In our study, sepsis was the main cause of death, and was responsible for 40% of patient mortalities. Additionally, we discerned that severe failure to thrive caused by prolonged hospitalization and repeated loss of blood constituents from the skin could lead to secondary immunosuppression, predisposing the patient to infection. In our study, prolonged hospitalization (median 41 days, range 14-290 days) was noted.

Death from failure to thrive is also a major concern, primarily in JEB.16 The cumulative and conditional risks of failure to thrive ranges from 40% to 44.7% by age 1, and rises to 61.8% with JEB by age 15. Sepsis, failure to thrive, and respiratory failure were the major causes of death in children with JEB, although these conditions plateaued by age 2 to 6.16 The Dutch EB Registry reported that, between 1988 and 2011, the average age at death was 5.8 months for 22 JEB-Herlitz type patients. These deaths were caused by, in order of prevalence, failure to thrive, respiratory failure, pneumonia, dehydration, anemia, sepsis, and euthanasia.17 Invasive treatments to extend life did not promote survival, and a higher birth weight did not predict a longer lifespan. However, patients with a sufficient initial weight gain did live significantly longer than patients with an insufficient or no initial weight gain.17 Therefore, the pattern of initial weight gain was suggested as a predictor of lifespan.17 In our study, 2 patients among five who died showed failure to thrive as cause of death. In our data, all five mortality cases showed a decrease in weight percentile compared with birth weight percentile. Only 6% of patients had an increased weight percentile compared with the initial weight percentile.

Failure to thrive is a term that is commonly used for any child who fails to gain weight or height according to standard medical growth charts.11 Identification of failure to thrive and assessment of the severity of an infant's nutritional state is important for providing appropriate intervention.10 However, surprisingly, there is currently no consistent definition about failure to thrive and it is difficult to recommend interventional measures.18 Failure to thrive is usually diagnosed when a child's weight for age or weight for height is falls below two major percentile lines.19 A thrive index is a z score for weight gain that is conditional on the infant's initial weight. Thus, it provides a measure of relative weight gain that is not confounded with birth weight. In our study, almost all patients showed appropriate weight for gestation at the time of birth, but at last follow up, all patients showed negative thrive index scores (poor weight gain for age) indicative of poor nutrition. Weight SD scores at birth and thrive index at scores last follow-up are shown in Fig. 1, and reflect overall growth failure in EB patients.

A complete cure for EB is currently impossible, although gene therapy, protein replacement, and bone marrow transplantation are all being investigated as possible curative treatments. Controlling infection, optimizing growth, wound healing, and providing the best possible overall quality of life are important for managing EB in children.20,21 However, these goals all require maintenance of optimal nutritional status. Because numerous complications occur with EB patients, such as inadequate skin care, poor dentition, esophageal stricture, gastroesophageal reflux, painful defecation, and psychological and psychosocial issues, it is important to consult with professionals from multiple disciplines to better manage EB treatment and nutritional intervention.22,23 From our results, we discerned that it may be important to consult a nutritional specialist and apply an high protein/calorie nutrition strategy to maintain and accelerate the patient's growth and development.

This study had some limitations due to the small number of subjects recruited from only two institutions. Nutritional and clinical outcomes among EB subtypes were not different, which possibly may be related to small numbers in the EB subgroups. Because our population was not a nation-wide registry, it may not reflect the overall outcomes of EBD in Korea. Therefore, it will be important to establish a national EB registry.

In conclusion, this is the first study to evaluate the growth and clinical outcomes of children with EB in Korea. Although sepsis developed in a relatively low number of patients, growth failure was a serious problem, possibly related to nutritional deficiencies. Strategies to maximize nutrition and growth status may affect outcomes for children with EB.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

For children with EB, thrive index at last follow-up plotted against weight standard at birth, reflecting poor weight gain as a negative index. Thrive index was not related to weight standard deviation score (SDS) at birth, and was not different between infection and non-infection subgroups. Black circles indicate EB patients with infection and open circles represent those without infection. EB, epidermolysis bullosa.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (No. 2011-0014207).

References

1. Sawamura D, Nakano H, Matsuzaki Y. Overview of epidermolysis bullosa. J Dermatol. 2010; 37:214–219.

2. Murat-Sušić S, Husar K, Skerlev M, Marinović B, Babić I. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa - the spectrum of complications. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2011; 19:255–263.

3. Fine JD, Mellerio JE. Extracutaneous manifestations and complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: part I. Epithelial associated tissues. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009; 61:367–384.

4. Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, Bauer JW, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Heagerty A, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): Report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008; 58:931–950.

5. Gonzalez ME. Evaluation and treatment of the newborn with epidermolysis bullosa. Semin Perinatol. 2013; 37:32–39.

6. Kho YC, Rhodes LM, Robertson SJ, Su J, Varigos G, Robertson I, et al. Epidemiology of epidermolysis bullosa in the antipodes: the Australasian Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry with a focus on Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146:635–640.

7. Rho YJ, Choi YA, Lee KS, Song JY. Epidemiologic study of epidermolysis bullosa in Korea. Korean J Dermatol. 1993; 31:931–936.

8. Fine JD, Mellerio JE. Extracutaneous manifestations and complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: part II. Other organs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009; 61:387–402.

9. Fewtrell MS, Allgrove J, Gordon I, Brain C, Atherton D, Harper J, et al. Bone mineralization in children with epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol. 2006; 154:959–962.

10. Moon JS, Lee SY, Nam CM, Choi JM, Choe BK, Seo JW, et al. 2007 Korean National Growth Charts: review of developmental process and an outlook. Korean J Pediatr. 2008; 51:1–25.

11. Wilcox WD, Nieburg P, Miller DS, et al. Failure to thrive. A continuing problem of definition. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1989; 28:391–394.

12. Boeira VL, Souza ES, Rocha Bde O, Oliveira PD, de Oliveira Mde F, Rêgo VR, et al. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa: clinical and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013; 88:185–198.

13. Fine JD. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa: recent basic and clinical advances. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010; 22:453–458.

14. Fine JD. Epidermolysis bullosa. Clinical aspects, pathology, and recent advances in research. Int J Dermatol. 1986; 25:143–157.

15. Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Suchindran C. Cause-specific risks of childhood death in inherited epidermolysis bullosa. J Pediatr. 2008; 152:276–280.

16. Yuen WY, Lemmink HH, van Dijk-Bos KK, Sinke RJ, Jonkman MF. Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa: diagnostic features, mutational profile, incidence and population carrier frequency in the Netherlands. Br J Dermatol. 2011; 165:1314–1322.

17. Yuen WY, Duipmans JC, Molenbuur B, Herpertz I, Mandema JM, Jonkman MF. Long-term follow-up of patients with Herlitz-type junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Dermatol. 2012; 167:374–382.

20. Martinez AE, Mellerio JE. Osteopenia and osteoporosis in epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol Clin. 2010; 28:353–355.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download