Abstract

Purpose

Materials and Methods

Results

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Flow diagram of HMV application. HMV, home mechanical ventilation; TMV, tracheostomy mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation. |

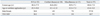

Table 1

HMV, home mechanical ventilation; TMV, tracheostomy mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

Values are mean±standard deviation. Others: Becker's muscular dystrophy (n=5), congenital myopathy (n=11), Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (n=2), fascioscapulohumeral dystrophy (n=6), limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (n=3), mitochondrial cytopathy (n=4), myotonic muscular dystrophy (n=13), non-specific progressive muscular dystrophy (n=23), inclusion body myositis (n=2), Klippel-Feil syndrome (n=1), critical illness myopathy (n=1), myotubular myopathy (n=1), nemaline myopathy (n=1), Nonaka myopathy (n=1), polimyositis (n=1), Pompe's disease (n=3), Swartz-Jampel syndrome (n=1).

Table 2

HMV, home mechanical ventilation; TMV, tracheostomy mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Values are mean±standard deviation. Miscellaneous: lung parenchymal disease (n=3) (s/p lung transplantation, bilateral phrenic N. palsy, Tuberculosis destroyed lung), Guillian-Barre syndrome (n=4), central hypoalveolarsyndrome (n=1), Down syndrome with obstructive sleep apnea (n=1), cor pulmonale due to kyphoscoliosis (n=2), myesthenia gravis (n=2).

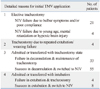

Table 3

DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SCI, spinal cord injury; FVCsit, forced vital capacity in sitting position; preFVCsit, normal predicted value of FVC in sitting position; FVCsup, forced vital capacity in supine position; preFVCsup, normal predicted value of FVC in supine position; PCF, peak cough flow; APCF, assisted peak cough flow; MIP, maximal inspiratory pressure; MIPpre, normal predicted value of MIP; MEP, maximal expiratory pressure; MEPpre, normal predicted value of MEP.

Miscellaneous: lung parenchymal disease (n=3), Guillian-Barre syndrome (n=4), central hypoalveolar syndrome (n=1), Down syndrome with obstructive sleep apnea (n=1), cor pulmonale due to kyphoscoliosis (n=2), myesthenia gravis (n=2). Values are mean±standard deviation.

*p<0.05, comparison of preFVCsit and preFVCsup in other myopathy group.

†p<0.05, comparison of preFVCsit and preFVCsup in ALS group.

‡p<0.05, comparison of preFVCsit and preFVCsup in SCI group.

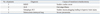

Table 4

HMV, home mechanical ventilation; TMV, tracheostomy mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SCI, spinal cord injury; PM&R, physical medicine and rehabilitation.

Values are mean±standard deviation. Others: Becker's muscular dystrophy (n=5), congenital myopathy (n=7), Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (n=2), fascioscapulohumeral dystrophy (n=5), limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (n=3), mitochondrial cytopathy (n=2), myotonic muscular dystrophy (n=10), non-specific progressive muscular dystrophy (n=18), inclusion body myositis (n=2), nemaline myopathy (n=1), Nonaka myopathy (n=1), polimyositis (n=1), Pompe's disease (n=2), Swartz-Jampel syndrome (n=1), Miscellaneous: central hypoalveolar syndrome (n=1), cor pulmonale due to kyphoscoliosis (n=2), myesthenia gravis (n=1).

Table 5-1

HMV, home mechanical ventilation; TMV, tracheostomy mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SCI, spinal cord injury; PM&R, physical medicine and rehabilitation.

Values are mean±standard deviation. Others: congenital myopathy (n=4), fascioscapulohumeral dystrophy (n=1), mitochondrial cytopathy (n=2), myotonic muscular dystrophy (n=3), nonspecific progressive muscular dystrophy (n=5), Klippel-Feil syndrome (n=1), critical illness myopathy (n=1), myotubular myopathy (n=1), Pompe's disease (n=1). Miscellaneous: lung parenchymal disease (n=3) (s/p lung transplantation, bilateral phrenic N. palsy, tuberculosis destroyed lung), Guillian-Barre syndrome (n=4), Down syndrome with obstructive sleep apnea (n=1), myesthenia gravis (n=1).

Table 6-1

HMV, home mechanical ventilation; TMV, tracheostomy mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Values are mean±standard deviation. Other myopathies: congenital myopathy (n=3), fascioscapulohumeral dystrophy (n=1), mitochondrial cytopathy (n=1), myotonic muscular dystrophy (n=1), non-specific progressive muscular dystrophy (n=2), Klippel-Feil syndrome (n=1), Pompe's disease (n=1). Miscellaneous: lung parenchymal disease (n=3) (s/p lung transplantation, bilateral phrenic N. palsy, Tbc dystroyed lung), Guillian-Barre syndrome (n=4), Down syndrome with obstructive sleep apnea (n=1), myesthenia gravis (n=1).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download