Abstract

Purpose

Roux-en-Y reconstruction (RY) in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer is a more complicated procedure than Billroth-I (BI) or Billroth-II. Here, we offer a totally laparoscopic simple RY using linear staplers.

Materials and Methods

Each 50 consecutive patients with totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with RY and BI were enrolled in this study. Technical safety and surgical outcomes of RY were evaluated in comparison with BI.

Results

In all patients, RY gastrectomy using linear staplers was safely performed without any events during surgery. The mean operation time and anastomosis time were 177.0±37.6 min and 14.4±5.6 min for RY, respectively, which were significantly longer than those for BI (150.4±34.0 min and 5.9±2.2 min, respectively). There were no differences in amount of blood loss, time to flatus passage, diet start, length of hospital stay, and postoperative inflammatory response between the two groups. Although there was no significant difference in surgical complications between RY and BI (6.0% and 14.0%), the RY group showed no anastomosis site-related complications.

In Korea, the main reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer surgery is gastroduodenostomy [Billroth I reconstruction (BI)]. When BI is difficult to perform because of tumor location or resection extent, gastrojejunostomy [Billroth II reconstruction (BII)] or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy (RY) is performed. Although the superiority of RY has been reported, such as less bile reflux compared to BI and BII, in several reports, BI and BII are preferred due to their technical simplicity. Therefore, RY has been the reconstruction method used the least after subtotal gastrectomy in Korea.1

Even in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy, BI and BII methods are also more widely adapted than RY because they have only one anastomosis.2 When gastroduodenostomy is performed during laparoscopic surgery, extracorporeal anastomosis through mini-laparotomy has been reported to be a safe procedure. However, the benefits of intracorporeal gastroduodenostomy have been reported recently.3,4 Gastrojejunostomy can easily be performed intracorporeally with a linear stapler. RY in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy is a more complicated procedure than BI or BII because it has two anastomoses. Therefore, several methods for laparoscopic RY were introduced: RY anastomosis through a mini-laparotomy, hand-sewing closure of the common entry hole to avoid anastomotic stenosis, and intracorporeal antiperistaltic reconstruction.5-8 Mini-laparotomy or hand sewing procedures during laparoscopic surgery are important, yet time consuming steps. Therefore, if all reconstruction procedures can be safely done with the intracorporeal approach using staplers, the use of RY can become easier and more widely adapted. Therefore, we attempted totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with isoperistaltic RY using linear staplers without the hand sewing technique, and evaluated the safety of our technique in 50 consecutive cases. In addition, we compared 50 RY procedures to the initial 50 consecutive cases of totally laparoscopic BI, which were used as a reference value.

Initial 50 consecutive patients who underwent totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with intracorporeal RY for gastric cancer by single surgeon between January 2011 and May 2012 were enrolled in this study. To evaluate the technical safety and surgical outcome of the RY procedure, data of initial 50 consecutive patients with totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with intracorporeal BI reconstruction done by same surgeon were used. The primary anastomotic option after distal gastrectomy is BI and RY is usually performed in cases where it is difficult to perform BI due to tumor location and size in our institute. Therefore, the indication of the two procedures and the tumor characteristics are different. As a result, data on BI, which is the most common and widely used procedure, was used as a reference value to evaluate the safety and acceptability of totally intracorporeal RY. Patients who underwent combined other organ resection such as cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and colectomy were excluded.

All patients had histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma in the stomach. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to surgery, and this study was Review Board of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine.

Under general anesthesia, patients were placed in the supine position. The surgeon stood on the right side and the first assistant on the left side. The camera assistant was on the right side of the surgeon. One 12-mm trocar was inserted through an infraumbilical incision using an open method. After a pneumoperitoneum was achieved, two 12-mm trocars were inserted in the right and left lower quadrants that were used for bowel resection and anastomosis with endoscopic linear staplers. Two 5-mm trocars were inserted in the right and left upper quadrants (Fig. 1).

For the processes of mobilizing the stomach and dissecting lymph nodes, laparoscopic coagulation shears (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA) were used. The duodenum was transected 1-2 cm distal to the pyloric ring using a linear stapler (Endo GIA Reload with Tri-Stapler 60 mm, Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA) through a 12-mm trocar in the right lower quadrant. Gastric resection was also done using two linear staplers (Endo GIA Reload with Tri-Stapler 60 mm, Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA) through the 12-mm trocar of the left lower quadrant.

For reconstruction, the jejunum was divided at 25 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz using a linear stapler. Then, a hole was made on the joining end of the stapling line and the greater curvature of the stomach using ultrasonic shears. The transected distal jejunum was brought up using the antecolic method, and a hole was made 7 cm distal to the jejunal transection line. A gastrojejunostomy was made using a linear stapler (Fig. 2A), and the common entry hole was also closed with a linear stapler (Endo GIA Reload with Tri-Stapler 60 mm, Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA) (Fig. 2B). The surgeon paid close attention to lift a minimum amount of tissue and the full thickness of the gastric and jejunal wall. In addition, during this procedure, the jejunum was transversely closed to provide a patulous lumen for gastric drainage. Although the common entry hole was located on the side of the food passage, the diameter of the jejunum was large enough to allow food passage (Fig. 2C).

To perform the jejunojejunostomy, a hole was made on the anti-mesenteric border of the jejunum 30 cm distal to the gastrojejunostomy and another hole on the anti-mesenteric end of the stapling line of the proximal jejunum previously transected. Each arm of the endoscopic linear stapler (Endo GIA Reload with Tri-Stapler 60 mm, Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA) was inserted into the proximal and distal jejunum, and a side-to-side anastomosis was performed (Fig. 3A). The common entry hole was closed using a linear stapler (Endo GIA Reload with Tri-Stapler 45 mm, Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA). In this procedure, it was important to transversely close the hole of the distal jejunum 30 cm distal from gastrojejunostomy for a patulous lumen (Fig. 3B and C). Then, a sufficient lumen size of the jejunum was secured for food passage (Fig. 3D). In this method, a total of eight linear staplers were used: one for duodenal resection, two for gastric resection, one for jejunal division, two for the gastrojejunostomy, and two for the jejunojejunostomy. In all cases, Petersen's defect was closed with interrupted suture.

A delta-shaped anastomosis was performed in the totally laparoscopic BI, as reported by Kanaya, et al.14 For this method, six linear staplers were used: one for duodenal resection, two for gastric resection, and three for the gastroduodenostomy. Other surgical processes except reconstruction were similar to those described here for the RY group.

Clinical characteristics such as age, gender, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, previous abdominal operation history, and body mass index (BMI) were analyzed. Factors associated with surgical techniques such as operation time, anastomosis time, and the amount of blood loss were measured during surgery and recorded immediately after surgery in the operation room. The operation time included procedures from skin incision to closure. In RY, anastomosis time included procedures only involving the jejunal division, gastrojejunostomy, jejunojejunostomy, and closure of the common entry hole. In BI, anastomosis time included procedures only involving the gastroduodenostomy and closing the common entry incision. Postoperative outcomes such as flatus passage time, hospital stay, diet, postoperative complications, and laboratory data were also evaluated. The surgical complications were graded by the Clavien-Dindo Classification.9 Pathological stage evaluation was based on the 7th edition of the International Union Against Cancer Classification. 10

Table 1 shows the clinical and operation-related factors for gastric cancer patients in the BI and RY groups. There were no differences in age, gender, ASA score, previous abdominal operation history, the extent of lymph node dissection, and the pathological results. For the RY group, patients had a higher BMI (p=0.004) and higher incidence of tumors located in middle third of the stomach (p<0.001).

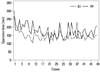

Because RY includes two anastomosis sites, the operation time and anastomosis time were longer for RY than for BI. As shown in Figs. 4 and 5, operation time and anastomosis time tended to decrease with the increase in completed case numbers. The mean differences in operation time and anastomosis time were about 27 min and 8 min, respectively. However, there was no difference in the amount of blood loss during surgery.

As described above, totally laparoscopic intracorporeal RY or BI gastrectomy using linear staplers was performed, no patients developed any complications or accidents during surgery, and there was no open conversion. In patients without surgical complications, the mean time to first flatus was 3.5 days for RY and 3.6 days for BI. A diet was started on postoperative day 3.6 days for RY and 3.8 days for BI, between which there was no statistically significant difference. The mean hospital stay was 7.2 days for RY and BI. As shown in Table 2, there were three (6.0%) postoperative complications in RY: one postoperative intraabdominal bleeding, one wound infection, and one pulmonary problem. All patients recovered without intervention or re-operation. There was no anastomotic or stump leakage and no anastomotic bleeding; thus, discontinuation or reversal of routine postoperative incrementation of food intake was not required. All patients tolerated a soft diet without any discomfort in the RY group. In the BI group, 7 (14.0%) showed postoperative complication: 2 delayed gastric emptying, 2 intraabdominal complicated fluid collections, 1 trocar site hernia, and 2 pulmonary problems. The patient with a trocar site hernia received hernia repair, and other 6 patients recovered without any intervention. Therefore, all the complications were grade II except trocar site hernia which was grade III based on the Clavien-Dindo Classification. There were no mortalities.

The white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil count, total protein and albumin were examined preoperatively, postoperatively, as well as postoperative days 1, 3, and 5. Serum high sensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was check at postoperative day, postoperative days 1, 3, and 5. All blood samples were obtained after an overnight fast. As shown in Fig. 6, the curves of RY and BI are parallel in each parameter and there were not statistically different between the groups.

The simplicity and safety of a surgical procedure is very important as it affects surgeons' preferences. Therefore, RY gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy is a less preferable surgical option for reconstruction regardless of its benefits. Although there have been several reports that RY is superior to BI after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer, the differences have not been enough to change surgeons' preferences.11-13 This may be the same case for open and laparoscopic surgeries.

In clinical practice, our primary choice of reconstruction is BI for laparoscopic surgery and BII or RY for tumors located in the mid-body or prepyloric antrum of the stomach. Such cases pose a difficult question to surgeons, as they must decide between BII and RY gastrojejunostomy. BII is relatively simple and fast, but it often causes alkaline reflux gastritis and esophagitis. RY less frequently develops reflux gastritis and esophagitis, but it requires two anastomoses, which means a longer operation time and more complexity. Therefore, if RY anastomoses can be performed more easily and conveniently, RY can be performed within a shorter operation time and may be preferred by more surgeons.

In our RY procedure, every anastomotic procedure was safely completed and simply performed with linear staplers. We used a linear stapler to close the common entry hole after gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy. There is concern that narrowing of the jejunal diameter of the gastrojejunostomy outlet could occur; therefore, some surgeons close the common entry hole with a hand sewing suture or make a common entry hole on the opposite side of the gastric outlet.5,8,14 Other authors suggested using a circular stapler through mini-laparotomy.7 However, we found that closing the common entry hole with a linear stapler can be safely completed and did not cause a stenosis of the gastrojejunostomy outlet. In our procedure, a linear stapler transversely closed the jejunum and did not resect excessive tissues, which is important to avoid stenosis at the stapling site. If the common entry hole of a gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy is transversely closed, the lumen is patulous for gastric drainage and food passage. In addition, a benefit of our technique is that every procedure can be done intracorporeally without mini-laparotomy or hand sewing, thereby requiring less time. Moreover, all procedures are performed in the same order as those of open gastrectomy.

For evaluating the surgical safety of initial RY experience after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy, we selected initial 50 patients with totally laparoscopic BI as a control group. Because the indication of BI and RY was different, we did not intended to show the superiority of RY, but to show the safety of RY in comparison to BI. The delta-shaped BI has been commonly used since introduced in 2002.15-18 As expected, operation time and anastomosis time were significantly longer for RY than for BI. However, the time difference between RY and BI appears to be sufficiently acceptable, and the operation time and anastomosis time decrease with the accumulation of case numbers. Because the indication for selecting the reconstruction method was different for BI and RY, tumor location was also different in both groups. However, postoperative courses were similar in both groups. Interestingly, there were no anastomosis-related complications with RY despite two anastomosis sites. Moreover, there was no delayed gastric emptying, which was a important concern of surgeons after RY gastrojejunostomy.13,19 This may be because the length of the Roux limb was about 30 cm in our patients. In addition, the changes of laboratory data reflecting inflammatory response such as WBC count, neutrophil count, and hsCRP after RY were similar to those of BI despite of longer operation time and more anastomotic sites in RY. Although our study included initial small number of cases, the lack of immediate postoperative anastomosis-related complications after RY and similar postoperative course of RY and BI reflect the safety of our RY technique.

In conclusion, the double stapling method using linear staplers in totally laparoscopic RY is a simple and safe method. This method could provide additional options for reconstruction when surgeons perform a laparoscopic distal gastrectomy.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Surgical techniques for gastrojejunostomy. (A) Side-to-side anastomosis between the greater curvature of the stomach and the jejunum with a linear stapler. (B) Closure of the common entry hole using a linear stapler. (C) Completion of the gastrojejunostomy.

Fig. 3

Surgical techniques for jejeunojejunostomy. (A) Side-to-side jejunojejunostomy using a linear stapler. (B and C) Closure of the common entry hole using a linear stapler. (D) Completion of the jejunojejunostomy.

Fig. 4

Operation time. Changes of operation time by case number accumulation for RY and BI. BI, Billroth-I; RY, Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

Fig. 5

Anastomosis time. Changes in anastomosis time by case number accumulation for RY and BI. BI, Billroth-I; RY, Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

Fig. 6

Changes of preoperative and postoperative laboratory data. (A) White blood cell count (WBC) (×103/µL), neutrophil (×103/µL), total protein (g/dL), albumin (mg/dL) level. (B) Serum high sensitive C-reactive protein level (mg/L). BI, Billroth-I; RY, Roux-en-Y reconstruction; POD, postoperative day.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0011301).

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (1320270).

References

1. The Information Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. 2004 Nationwide Gastric Cancer Report in Korea. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2007; 7:47–54.

2. Kang KC, Cho GS, Han SU, Kim W, Kim HH, Kim MC, et al. Comparison of Billroth I and Billroth II reconstructions after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy: a retrospective analysis of large-scale multicenter results from Korea. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:1953–1961.

3. Kim MG, Kawada H, Kim BS, Kim TH, Kim KC, Yook JH, et al. A totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with gastroduodenostomy (TLDG) for improvement of the early surgical outcomes in high BMI patients. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:1076–1082.

4. Kim BS, Yook JH, Choi YB, Kim KC, Kim MG, Kim TH, et al. Comparison of early outcomes of intracorporeal and extracorporeal gastroduodenostomy after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011; 21:387–391.

5. Takaori K, Nomura E, Mabuchi H, Lee SW, Agui T, Miyamoto Y, et al. A secure technique of intracorporeal Roux-Y reconstruction after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Am J Surg. 2005; 189:178–183.

6. Bouras G, Lee SW, Nomura E, Tokuhara T, Nitta T, Yoshinaka R, et al. Surgical outcomes from laparoscopic distal gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction: evolution in a totally intracorporeal technique. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011; 21:37–41.

7. Kim DH, Kim HY, Kim DH, Jeon TY, Hwang SH, Kim GH. Double stapling Roux-en-Y reconstruction in a laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Surg Today. 2010; 40:943–948.

8. Kojima K, Yamada H, Inokuchi M, Kawano T, Sugihara K. A comparison of Roux-en-Y and Billroth-I reconstruction after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008; 247:962–967.

9. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009; 250:187–196.

10. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. Springer;2010.

11. Nunobe S, Okaro A, Sasako M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Katai H, et al. Billroth 1 versus Roux-en-Y reconstructions: a quality-of-life survey at 5 years. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007; 12:433–439.

12. Fukuhara K, Osugi H, Takada N, Takemura M, Higashino M, Kinoshita H. Reconstructive procedure after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer that best prevents duodenogastroesophageal reflux. World J Surg. 2002; 26:1452–1457.

13. Hoya Y, Mitsumori N, Yanaga K. The advantages and disadvantages of a Roux-en-Y reconstruction after a distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2009; 39:647–651.

14. Noshiro H, Ohuchida K, Kawamoto M, Ishikawa M, Uchiyama A, Shimizu S, et al. Intraabdominal Roux-en-Y reconstruction with a novel stapling technique after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2009; 12:164–169.

15. Kanaya S, Gomi T, Momoi H, Tamaki N, Isobe H, Katayama T, et al. Delta-shaped anastomosis in totally laparoscopic Billroth I gastrectomy: new technique of intraabdominal gastroduodenostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2002; 195:284–287.

16. Lee HW, Kim HI, An JY, Cheong JH, Lee KY, Hyung WJ, et al. Intracorporeal Anastomosis Using Linear Stapler in Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy: Comparison between Gastroduodenostomy and Gastrojejunostomy. J Gastric Cancer. 2011; 11:212–218.

17. Kanaya S, Kawamura Y, Kawada H, Iwasaki H, Gomi T, Satoh S, et al. The delta-shaped anastomosis in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: analysis of the initial 100 consecutive procedures of intracorporeal gastroduodenostomy. Gastric Cancer. 2011; 14:365–371.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download