Abstract

Purpose

Optimal analgesia in ambulatory urology patients still remains a challenge. The aim of this study was to examine if the pre-emptive use of intravenous tramadol can reduce pain after ureteroscopic lithotripsy in patients diagnosed with unilateral ureteral stones.

Materials and Methods

This prospective pilot cohort study included 74 patients diagnosed with unilateral ureteral stones who underwent ureteroscopic lithotripsy under general anesthesia in the Urology Clinic at the Clinical Center of Serbia from March to June 2012. All patients were randomly allocated to two groups: one group (38 patients) received intravenous infusion of tramadol 100 mg in 500 mL 0.9%NaCl one hour before the procedure, while the other group (36 patients) received 500 mL 0.9%NaCl at the same time. Visual analogue scale (VAS) scores were recorded once prior to surgery and two times after the surgery (1 h and 6 h, respectively). The patients were prescribed additional postoperative analgesia (diclofenac 75 mg i.m.) when required. Pre-emptive effects of tramadol were assessed measuring pain scores, VAS1 and VAS2, intraoperative fentanyl consumption, and postoperative analgesic requirement.

Results

The average VAS1 score in the tramadol group was significantly lower than that in the non-tramadol group. The difference in average VAS2 score values between the two groups was not statistically significant; however, there were more patients who experienced severe pain in the non-tramadol group (p<0.01). The number of patients that required postoperative analgesia was not statistically different between the groups.

Optimal postoperative analgesia in ambulatory urology surgery still remains a challenge. According to McGrath, there are still a lot of patients who suffer moderate to severe pain after one-day surgery, even though theoretical knowledge in pain management progresses rapidly.1 Patients diagnosed with ureteric stones have been successfully treated with ureteroscopic lithotripsy (URSL) with the "Lithoclast" device in our hospital. The intervention is performed under general anesthesia, mostly as a one day surgery. The procedure carries a risk of moderate to severe postoperative pain, and so far postoperative pain management has remained unsatisfactory in most of patients.2

Pre-emptive analgesic strategies are strongly recommended by the International Association for the study of pain, especially in low-resource settings.3 Pre-emptive analgesia is an antinociceptive treatment that prevents establishment of altered processing of afferent input that amplifies postoperative pain.4 In other terms, it can be defined as an analgesic intervention provided before surgery to prevent or reduce subsequent pain.5,6 Tramadol hydrochloride is widely used in everyday anesthesia practice and its monoaminergic activity makes it suitable for pre-emptive analgesic treatment, especially for short surgical procedures.7,8 The aim of this study was to examine if the pre-emptive use of intravenous tramadol can reduce pain after URSL in patients diagnosed with unilateral ureteral stones.

Following ethics committee approval, informed consent was obtained for 78 consecutive American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I and II patients diagnosed with unilateral ureteral stones. These patients were scheduled for URSL and included in this prospective pilot cohort study. The study period ran from March till June 2012.

The exclusion criteria were age less than 18 years and older than 70 years, allergies to tramadol, long term use of opioid medications, MAO inhibitor therapy, epilepsy, liver and/or kidney dysfunction, and history of alcohol or drug abuse. Other exclusion criteria included patients diagnosed with bilateral ureteral stones, those with a JJ stent placed at the end of the procedure, and urgent cases involving urinary obstruction.

There were 78 patients enrolled in this study. However, two were excluded due to prolonged hospital stay and two more due to lack of cooperation. Overall, the number of patients included was 74, from which 38 were allocated to the tramadol group and 36 to the non-tramadol group.

Demographic data and history of previous surgeries and URSL were obtained on admission to the hospital. The effects of tramadol, as well as visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, were thoroughly explained. Patients were told that the pain scores would be recorded once prior to and twice after the procedure.

Routine biochemistry analysis, blood count, urinalysis, and urine culture were performed preoperatively. Prophylactic antibiotics were injected intravenously in all patients.

The study was conducted in a double blinded manner. All patients were randomly allocated into two groups using random allocation software (block randomization). Group I (the tramadol group, 38 patients) received tramadol infusion 100 mg i.v. in 500 mL 0.9%NaCl, 10 mL/min one hour before the procedure. Group II (non-tramadol group, 36 patients) received only 0.9%NaCl 500 mL infusion one hour before the procedure. The infusions were prepared and code labeled by an anesthetist and anesthetic nurse who were involved in neither anesthesia administration nor in observation processes.

VAS scores were recorded once prior to the infusion and twice after the surgery. VAS1 score was recorded one hour after the termination of the procedure and VAS2 at 6 hours after the procedure. VAS is a simple and frequently used method for the assessment of variations in intensity of pain. The test has a sensitivity of 88.9% and specificity of 62.2%.

Patients received premedication, midazolam 0.1 mg/kg 30 min prior to induction. Intraoperative monitoring included pulse oximetry, automated blood pressure cuff, and ECG. Anesthesia was induced with propofol 1.5 mg/kg, followed by laryngeal mask airway insertion. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane 1 MAC and fentanyl 2 mcg/kg. Spontaneous respiration was maintained, whereas artificial support was provided when respiratory rate dropped below 8 respirations per minute. Lidocaine gel 2% was applied locally to all patients before the beginning of the endoscopic procedure.

The URSL procedure was performed using a "Lithoclast." The Lithoclast is an impact device that uses pneumatic force in order to break the stone; it is placed endoscopically via a rigid ureteroscope. The endpoint of the intervention is fragmentation of the stone into small pieces. Fragmented stones can be removed out of the ureter using a basket or forceps, but many of them spontaneously pass through the ureters.

After emerging from anesthesia, patients were transferred to a recovery room where VAS1 score was recorded one hour postoperatively. Fully recovered patients were moved to the ward and consequently sent home when discharge criteria were achieved. While in the ward, VAS2 was recorded six hours after the end of the surgery. Patients received analgesia when required. According to our hospital protocol patients are not prescribed regular analgesia for short endoscopic procedures. The non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) diclofenac was prescribed when required. Data on analgesic requirement were collected after discharge.

Discharge criteria were as follows: patient fully awake, able to take a deep breath and cough, pulse and blood pressure within 20% of preoperative values, patients were able to pass urine spontaneously, there was no presence of large blood cloths in urine, and no fever (t >38℃).

Pre-emptive effects of tramadol were assessed measuring the pain scores VAS1 and VAS2, intraoperative fentanyl consumption, and postoperative analgesic requirement.

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package SPSS version 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data are expressed as mean (±SD) or median (range). Categorical data are presented as frequencies. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t-test and categorical variables were compared using a non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney U test, Wilcoxon's rank sum test, χ2 test, and Fisher's exact test). Spearman correlation was used to analyze associations between continuous (duration of the procedure) and categorical data (VAS score). Ordinal data (VAS) were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered significant for all tests. Multiple regression analysis was used to examine patients characteristics (independent variables) according to VAS score.

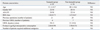

There were no differences in patients characteristics (age, gender, ASA status, BMI), number of previous operations, and URSL interventions between the two groups (Table 1). The average duration of the procedure was 19 minutes (10-45 minutes) in the tramadol group and 21.5 minutes (10-35 minutes) in the non-tramadol group (Table 1). There was no correlation between the duration of the procedure and the intensity of early (VAS1) and late (VAS2) postoperative pain (Spearman's rho 0.12 and 0.21, respectively). Intraoperative fentanyl consumption was similar in both groups (2.04±0.98 µgr/kg in the tramadol group and 1.98±0.76 µgr/kg in the non-tramadol group, p=0.413) (Table 1).

All patients were pain free prior to infusion, except for two patients who reported a VAS score of 2. Multivariate statistical analysis showed that VAS1 and VAS2 values were not influenced by patient characteristics. Also, number of previous operations, as well as the number of previous URSL procedures, did not have an effect on VAS scores (p=0.66 and 0.78 respectively). Early (VAS1) and late (VAS2) postoperative pain were not affected by the intraoperative fentanyl consumption (p=0.59 and p=0.18).

Pre-emptive use of tramadol resulted in a reduction of early postoperative pain (VAS1). There was a statistically significant difference in average VAS1 scores between the tramadol and non-tramadol group (0.68±1.09 vs. 3.22±3.60, p<0.01) (Fig. 1). The number of pain free patients (VAS1=0) in the tramadol group was 24 (63.16%), compared to 16 (44.44%) in the non-tramadol group (p=0.62). The maximum VAS1 score in the tramadol group was 3, whereas in the non-tramadol group, there were 12 patients (33.33%) who reported high VAS1 scores ≥7 (p<0.01).

The average VAS2 score in the tramadol group (3.68±2.13) was lower than that in the non-tramadol group (5.00±3.73), although without statistical significance (p=0.089) (Fig. 1). However, patients in both groups experienced greater pain at 6 hours after the intervention, and this increase was statistically significant (p<0.01). The number of patients who experienced severe pain (VAS2 ≥7) in the non-tramadol group was 4 (10.52%), compared to 16 (44.44%) (p<0.05) in the non-tramadol group (Fig. 2).

There was no difference in number of patients who received postoperative analgesia (when required) between the two groups. Eighteen of 38 patients in the tramadol group and 24 of 36 patients in the non-tramadol group required additional analgesia (p=0.15) (Table 1). The average VAS1 among patients who received the NSAID diclofenac was 1.33±1.74 in the tramadol group and 4.79±3.18 in the non-tramadol group. Although they did receive analgesic, VAS2 scores were higher in both groups (5.28±2.58 in the tramadol group and 6.87±2.25 in the non-tramadol group) with a statistically significant increase in both the tramadol and non-tramadol groups (p<0.01 and p=0.012, respectively). Patients who did not require any additional analgesia were the patients who reported no pain (VAS1=0) one hour after the procedure (20 patients in the tramadol and 12 patients in the non-tramadol group). Their VAS2 scores were 1.33±1.97 and 2.33±1.49, respectively.

Statistical analyses revealed no significant differences in patient's characteristics, number of previous operations, and URSL interventions between patients who did not require analgesia (VAS1=0) and those who did.

Aiming to improve postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing ureteroscopic stone removal, we examined the pre-emptive use of tramadol and evaluated its effects. According to Carrión López, et al.9 pain was the most frequent problem identified among 4185 patients who underwent ambulatory urology surgery. Tramadol was chosen in this particular setting because it can be safely administered pre- and intraoperatively as a pre-emptive or preventive analgesia without modification of the depth of anesthesia according to Fodale, et al.10 Also, previous studies failed to demonstrate the efficiency of pre-emptive analgesia with the non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen in patients undergoing urology surgery.11

There were two main findings in this study. First was that tramadol showed pre-emptive potential and diminished early postoperative pain, with a reduction in VAS1 scores.

Our success with pre-emptive tramadol for early pain control correlates with findings from some other studies. In a previous study, Wordliczek, et al.8 showed that pre-emptive and/or preventive use of tramadol significantly reduces opioid requirement in the early postoperative period, confirming the possibility that tramadol may inhibit the activation of sensitization processes connected with phase I of the nociceptive information flow. Shen, et al.12 found in their study that the pre-emptive and preventive use of intravenous tramadol alleviates pain after lumpectomy, as well as reduces postoperative morphine consumption. Additionally, Aida, et al.13 showed that preemptive analgesia is effective in limb surgery or mastectomy, but has no effects in abdominal surgery. In our study, the reduction in VAS1 scores was significant. All patients in the tramadol group reported satisfactory analgesia, meaning that all VAS1 scores were less than or equal to 3.

The second finding was that pre-emptive use of tramadol did not significantly reduce average VAS2 score, although it did influence the development of severe pain. Only 4 patients in the tramadol group had VAS2 scores of 7.0 or more, compared to 16 in the non-tramadol group.

This supports the results from other studies. Møiniche, et al.14 in their meta-analysis of 80 trials showed that average VAS scores recorded at 24 hours after operation did not significantly improve after pre-emptive treatment. Katz, et al.15 found that pre-emptive use of intravenous fentanyl plus low-dose ketamine for radical prostatectomy under general anesthesia does not produce short-term or long-term reductions in pain or analgesic use. So far, studies concerning pre-emptive analgesia in endoscopic urology surgery have not yet been conducted.

The number of patients who required additional analgesia (NSAID diclofenac according to hospital protocol) did not statistically differ between the tramadol and non-tramadol groups. Despite the fact that they did receive the analgesic, significant increase in VAS2 scores was recorded. The type of analgesia was clearly insufficient for optimal postoperative pain control in our patients. The average VAS2 scores in patients from the tramadol group who received diclofenac were less than in those in the non-tramadol group; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, number of patients requiring additional analgesia is not a good parameter for demonstrating the preemptive effects of an analgesic regimen.16

However, pain experienced at 6 hours after an intervention can be explained as a two-component pain: one as a consequence of the endoscopic procedure itself and the other caused by passing stones trough the ureters.8 A weak opioid, such as tramadol, pre-emptively given without adequate postoperative analgesia would hardly be enough for controlling this type of pain.

Also, in our study VAS2 was measured at 6 hours after the termination of the procedure, which was at least 7.5 hours after tramadol administration. This fact associated with tramadol pharmacokinetics (half-life of 6.3±1.4) could explain the high average VAS2 score for both groups. Postoperative analgesia provided in the ward was clearly insufficient for our patients who experienced moderate to severe pain. A multimodal approach including pre-emptive tramadol and a stronger postoperative analgesia (paracetamol plus NSAID and/or opioids) would be a preferable analgesic strategy for our patients.

The limitations of this study included short-term postoperative pain assessment, non-consistent postoperative follow-up of the stone fragment removal rate, and the lack of regular postoperative analgesic prescription for patients undergoing URSL procedure.

In conclusion, pre-emptive tramadol did reduce early postoperative pain. Moreover, patients who received preemptive tramadol were less likely to experience severe post-operative pain. Further clinical trials are required to investigate the efficacy of pre-emptive analgesia in endourological procedures.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study received Ethical Committee approval No. 2953/6, on March 15, 2012, from the Ethical Committee of the Clinical Center of Serbia, Chairmen Professor Z. Maksimovic, MD., PhD.

References

1. McGrath B, Elgendy H, Chung F, Kamming D, Curti B, King S. Thirty percent of patients have moderate to severe pain 24 hr after ambulatory surgery: a survey of 5,703 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2004; 51:886–891.

2. Jeong BC, Park HK, Kwak C, Oh SJ, Kim HH. How painful are shockwave lithotripsy and endoscopic procedures performed at outpatient urology clinics? Urol Res. 2005; 33:291–296.

3. Amata A. Pain Management in Ambulatory/Day Surgery. In : Kopf A, Patel NB, editors. Guide to Pain Management in Low-Resource Settings. Seattle: IASP;2010. p. 119–121.

6. Unlugenc H, Ozalevli M, Gunes Y, Guler T, Isik G. Pre-emptive analgesic efficacy of tramadol compared with morphine after major abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2003; 91:209–213.

7. Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, Shank RP, Codd EE, Vaught JL. Opioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an 'atypical' opioid analgesic. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992; 260:275–285.

8. Wordliczek J, Banach M, Garlicki J, Jakowicka-Wordliczek J, Dobrogowski J. Influence of pre- or intraoperational use of tramadol (preemptive or preventive analgesia) on tramadol requirement in the early postoperative period. Pol J Pharmacol. 2002; 54:693–697.

9. Carrión López P, Cortiñas Sáenz M, Fajardo MJ, Donate Moreno MJ, Pastor Navarro H, Martínez Córcoles B, et al. [Ambulatory surgery in a urology department. Analysis of the period 2003-2006]. Arch Esp Urol. 2008; 61:365–370.

10. Fodale V, Tescione M, Roscitano C, Pino G, Amato A, Santamaria LB. Effect of tramadol on Bispectral Index during intravenous anaesthesia with propofol and remifentanil. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006; 34:36–39.

11. Rutyna R, Popowicz M, Wojewoda P, Nestorowicz A, Białek W. [Pre-emptive ketoprofen for postoperative pain relief after urologic surgery]. Anestezjol Intens Ter. 2011; 43:18–21.

12. Shen X, Wang F, Xu S, Ma L, Liu Y, Feng S, et al. Comparison of the analgesic efficacy of preemptive and preventive tramadol after lumpectomy. Pharmacol Rep. 2008; 60:415–421.

13. Aida S, Baba H, Yamakura T, Taga K, Fukuda S, Shimoji K. The effectiveness of preemptive analgesia varies according to the type of surgery: a randomized, double-blind study. Anesth Analg. 1999; 89:711–716.

14. Møiniche S, Kehlet H, Dahl JB. A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain relief: the role of timing of analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2002; 96:725–741.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download