Abstract

Purpose

The prognosis of breast cancer has been consistently improving. We analyzed our cohort of breast cancer patients with a long-term follow up at a single center over time.

Materials and Methods

A total of 1889 patients with known cancer stages were recruited and analyzed between January 1991 and December 2005. Patients were classified according to the time periods (1991-1995; 1996-2000; 2001-2005). To determine intrinsic subtypes, 858 patients whose human epidermal growth receptor-2 status and Ki67 were reported between April 2004 and December 2008 were also analyzed.

Results

At a median follow up of 9.1 years, the 10-year overall survival (OS) rate was 80.5% for the entire cohort. On multivariate analysis for OS and recurrence-free survival (RFS), the time period was demonstrated to be a significant factor independent of conventional prognostic markers. In the survival analysis performed for each stage (I to III), OS and RFS significantly improved according to the time periods. Adoption of new agents in adjuvant chemotherapy and endocrine therapy was increased according to the elapsed time. In the patients with known subtypes, OS and RFS significantly differed among the subtypes, and the triple-negative subtype showed the worst outcome in stages II and III.

Conclusion

In the Korean breast cancer cohort with a long-term follow up, our data show an improved prognosis over the past decades, and harbor the contribution of advances in adjuvant treatment. Moreover, we provided new insight regarding comparison of the prognostic impact between the tumor burden and subtypes.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, with about 1.5 million new cases being diagnosed annually worldwide, a lifetime risk of up to 12%, and a risk of death of up to 5% in Western countries.1 The incidence of breast cancer in Korea has been increasing constantly, although it remains low compared with its incidence in Western countries.2,3,4,5 According to the hospital-based cancer registry called the Korea Central Cancer Registry, the age-standardized breast cancer incidence rate per 100000 was 20.9 in 1999, and it was exponentially elevated to 39.8 in 2010, providing an annual percent change of 6.3%.6 Based on this national-wide database, the breast was the second most common cancer site following the thyroid in year 2010 and comprised 14.3% of all female cancers.6

Although there is an increasing incidence of breast cancer in Korea, the survival outcome of breast cancer patients has also markedly improved. The 5-year survival rate between 1993 and 1995 was 78.0%, and that rate jumped up to 89.5% between 2003 and 2007.2 Many reports have provided relevant explanations for the recent survival improvement in breast cancer patients. In part, the incline in survival rate can be attributed to nationwide screening programs, with expansion of a proportion of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ and early breast cancer.7 Other reasons for these improvements are the advances in adjuvant treatment, which includes the increasing use of adjuvant anthracycline-based regimens or taxane-based regimens8,9 and clinical adoption of new agents: for instance, aromatase inhibitors for hormone receptor-positive tumors and the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab for human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2)-positive tumors.10,11 However, almost all these studies have been reported in Western countries, in which Asian races had seldom participated. In contrast to these countries, very few investigations have been reported to explain the underlying cause of the survival improvement of Korean breast cancer patients over time. Thus, it would be clinically relevant to discriminate the influences between the incremental changes in early-stage cancer and time periods that suggest the advancement in cancer management.

Recently, molecular subtyping of breast cancer was logically accepted in clinical practice12,13 hence, the prognostic influence of the subtypes has become increasingly important. Therefore, we explored survival analysis according to subtype in the present investigation.

To discriminate the impact on survival between tumor stage and time periods, we analyzed survival outcome according to the time trend at a single institution. We sought to delineate the improving trend of survival outcome according to time periods at each stage and uncover factors of survival prolongation using our database of well over 1000 patients. To evaluate a prognostic influence of the intrinsic subtypes, we compared survival among subtypes defined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) markers.

A prospectively maintained database of breast cancer patients treated at Gangnam Severance Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea, was used to identify patients who underwent operation with a diagnosis of breast cancer between January 1991 and December 2005. The period was divided into three corresponding periods: 1991-1995, 1996-2000, and 2001-2005. The follow-up protocol included planned regular visits every 6 months and requests for missed appointments with a telephone call were made to minimize patient loss and raise the accuracy of survival data. The last update of the clinical database was in September 2012. Among the patients receiving an operation, six male patients with breast cancer, one patient with occult cancer, and 18 patients with breast cancer of non-epithelial origin (such as a phyllodes tumor, sarcoma, or lymphoma) were excluded. For survival analysis based on stages, patients with an unknown tumor size and nodal status were also excluded. Bilateral breast cancer was counted as a single patient. Finally, 1889 patients were included in the primary analysis. The institutional review board of Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, approved the study to be in accordance with good clinical practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki (Local IRB number: #3-2013-0152). The need for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design.

For analysis using intrinsic subtypes, we required information regarding HER-2 status. However, we reported reliable HER-2 data from the institute for April 2002. Therefore, to overcome a small sample size of analysis based on subtypes, with a restriction to this analysis, we extended the study period to December 2008. As a result, 858 patients treated between April 2004 and December 2008 were included in the present analysis.

The staging system was based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), 6th edition.14 We revised the final stage according to the criteria. In synchronous bilateral breast cancer, the higher stage between two tumors was selected. In metachronous bilateral breast cancer, the stage of the first cancer was chosen. In patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the clinical stage before neoadjuvant chemotherapy was applied.

During the process of collecting information on adjuvant treatment, we investigated the change in drug regimen according to the time period. We obtained information regarding changing regimens with endocrine therapy. Radiotherapy data were not included.

With regard to biomarker assays, before February 1999, estrogen receptor (ER) status was determined using the ligand binding assay, and tumors were considered ER positive with a score greater than 10 fmol/mg.15 After February 1999, the IHC method for ER staining was introduced and replaced the biochemical method. Likely, progesterone receptor (PR) expression was measured based on the ligand binding assay before 1999 and the IHC method after that time. As mentioned earlier, refined IHC evaluation for HER-2 was established from April 2002 at our institute. HER-2 positivity was assessed by three positive results on IHC examination or fluorescence in situ hybridization amplification. Since March 2002, Ki67 labelling index using MIB-1 monoclonal antibodies was clinically applied in our pathologic laboratory. Ki67 expression was measured by an experienced pathologist and was presented as a percentage score (from 0 to 100). Ki67 staining was stratified as a high or low score with a cut-off value of 14%.

For the intrinsic sub-classification, we analyzed the 858 patients with information regarding ER, PR, HER-2, and Ki67 status. According to the criteria suggested by the St. Gallen panelists,16 we classified four subtypes as follows: luminal A (ER-positive and/or PR-positive, HER-2-negative and Ki-67 <14%); luminal B (ER-positive and/or PR-positive, HER-2-negative, and Ki67 ≥14% or ER-positive and/or PR-positive and HER-2-positive, and any Ki67); HER-2 (ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER-2-positive); and triple-negative breast cancer (ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER-2-negative).

We reviewed the medical records for any discrepancies in the information and pathologic data of the patients and summarized the clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients and details of adjuvant treatment.

Discrete variables were compared by χ2 test. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of the first curative surgery to the date of the last follow up or death from any cause during follow up. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was measured from the date of the first curative surgery to the date of the first locoregional or distant metastasis, or death without any type of relapse. Survival curves based on the Kaplan-Meier method were compared using the log-rank test. Factors, which were significantly demonstrated in the univariate analyses, were used in the multivariate analyses. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the effect of each potential prognostic variable on survival. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. The software used to perform these analyses was the SPSS version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

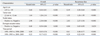

In 1889 patients, we compared baseline characteristics according to the corresponding time period (Table 1). According to the elapsed time, patients aged 40-49 years and 50-59 years showed a peak breast cancer incidence (41.0% and 23.1%, respectively), followed by patients aged 30-39 years (20.2%). These peak ages are concordant with breast cancer in Korea and are different from those observed in Western countries. In our cohort, pure in situ carcinoma was diagnosed in 9.3% of the patients, and invasive carcinoma occurred in 91.7% of the patients. The composition of T stage was not significantly changed, but the proportion of N stage showed a significant change according to the time period. As a result, the proportion of stage 0 and I increased from 37.3% from 1991 to 1995 to 42.7% during 15 years. The composition of high histologic grade was not associated with elapsed time (Table 1). The rate of positive ER among the patients with known ER status was not significantly different (58.9% in 1991-1995, 59.3% in 1996-2000, and 61.7% in 2001-2005; p=0.528). The results were similar for PR.

During the follow-up periods, 303 breast cancer-specific mortalities and 49 non-cancer related deaths occurred. At a median follow up of 9.1 years, the 10-year OS rate was 80.5% [95% confidence interval (CI), 79.5-81.5%] for the entire cohort. Tumor stages according to AJCC classification of the 1889 patients were as follows: stage 0 in 176 (9.3%), stage I in 540 (28.6%), stage II in 804 (42.6%), stage III in 871 (17.4%), and stage IV in 40 (2.1%) patients. The 10-year OS rates by each stage were 97.3% (95% CI, 96.0-98.6%) for stage 0, 91.4% (95% CI, 90.0-92.8%) for stage I, 83.5% (95% CI, 82.0-84.0%) for stage II, 53.1% (95% CI, 50.0-56.2%) for stage III, and 12.0% (95% CI, 6.7-17.3%) for stage IV.

We noted the increased rate of early breast cancer over time. Additionally, the patients in stage IV without breast surgery were not completely registered in the database; thus, our data could not represent survival of stage IV disease. Therefore, to evaluate the effect of the time periods, we performed survival analysis in patients with stage I to III disease according to the time period. In 1673 patients with stage I-III disease, the 7-year OS rates were 76.2% for 1991-1995, 82.1% for 1996-2000, and 93.7% for 2001-2005 (p<0.001) (Fig. 1A). The 7-year RFS rates were 65.6% for 1991-1995, 75.4% for 1996-2000, and 88.2% for 2001-2005 (p<0.001) (Fig. 1B).

To discriminate between the impact of tumor stage and the time periods on survival, we performed survival analysis by each stage (Fig. 2). In patients with stage I disease, survival significantly differed according to the time period. For these patients, however, OS and RFS did not seem to be much different between the 1991-1995 and 1996-2000 time periods (Fig. 1). In contrast to stage I, the difference between OS and RFS became larger in stage II or III by every time period (Fig. 2C-F). We found that mortality reduction and recurrence reduction according to the time period were mainly achieved in stages II-III.

In the final step, we performed multivariate survival analysis (Table 2). In this analysis, the time factor was demonstrated to be a significant prognostic factor for OS and RFS independent of age, tumor size, nodal status, and ER status.

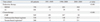

We investigated the regimens of chemotherapy and endocrine therapy, which reflected the advancement of cancer management (Table 3). For endocrine therapy, selective ER modulators were the only option during 1991-1995. However, aromatase inhibitors were introduced clinically during 1996-2000, and their use was expanded during 2001-2005. For chemotherapy, the use of an anthracycline-based regimen was constantly expanded during 15 years. The rate of anthracycline-based regimen use was 57.6% during 2001-2005, whereas it was 33.0% during 1991-1995. At our institute, taxane-related regimens were first prescribed during 1996-2000. Since then, they have become widely used in clinical practice, with 37.1% of patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy during 2001-2005.

To evaluate the prognostic value of breast cancer subtypes, we performed survival analysis with subtypes defined by IHC markers. Stages of all patients were also I-III. Among the 858 patients with known molecular subtypes, luminal A, luminal B, HER-2, and triple-negative subtypes were 375 (43.8%), 190 (22.1%), 134 (15.6%), and 159 (18.5%), respectively. At a median follow up of 5.5 years, OS and RFS significantly differed among the groups classified by subtypes on the log-rank test (Fig. 3A and B). In univariate analysis for OS, luminal A showed the best survival, whereas the triple-negative type showed the worst outcome (Fig. 3A). The 5-year RFS rate was 94.2% in luminal A, 87.5% in luminal B, 85.4% in HER-2, and 85.9% in triple-negative subtypes (Fig. 3B).

To compare the influence on survival of the subtypes with tumor burden, we conducted survival analysis using the subtypes according to each stage. Among 326 patients with stage I disease, a significant difference in RFS and OS was not found among the subtypes (p=0.517 and p=0.747, respectively) (Fig. 3C and D). Of the 532 patients with stage II and III disease, RFS and OS were significantly different according to subtype (p<0.001 and p=0.003, respectively) (Fig. 3E and F). For these patients in stage II and III, the triple-negative subtype showed a worse OS than the best results observed in the luminal A subtype (Fig. 3E). These findings suggest that the influence of subtype has been attenuated in survival of early breast cancer.

In the first part of the present study, we evaluated the factors associated with survival improvement in breast cancer using the database of a single institution, which is prospectively maintained and less affected by an interdisciplinary variability. We found that the time period played a major role in the survival improvement of Korean breast cancer patients. Until now, this advance in survival outcome by time trend has been mainly explained by the increasing proportions of early-stage cancer. It has been suggested that the wide application of newly developed agents in chemotherapy or endocrine therapy may be an underlying cause. In our results, an incremental trend in the proportion of stage 0 and I disease was similarly noted (37.3% during 1991-1995 to 42.7% during 2001-2005).

To discriminate the influences on survival improvement between increases in early breast cancer and advances of adjuvant therapy, we performed multivariate survival analysis, including the time factor and survival analysis in each stage among the patients with AJCC stages I-III. The contributions of the time factor to survival improvement were observed independent of other important factors such as age, tumor size, nodal status, and ER status (Table 2). Moreover, survival gains brought by elapsed time have been achieved in each stage (Fig. 2). Obviously, this phenomenon was remarkable in stages II and III. To indirectly evaluate the influence of changing regimens in adjuvant therapy, we compared the types of regimens used in endocrine therapy and chemotherapy among the time periods, and our analysis showed that the proportion of new agents of chemotherapy and endocrine therapy incrementally changed over time. Advancement in adjuvant therapy may be associated with survival improvement of breast cancer patients during the investigated period, particularly in the patients with locally advanced breast cancer.

In the previous study based on a large cohort of Korean breast cancer patients,5 an enhanced survival outcome by time trend was reported. However, they suggested the expansion of early-stage breast cancer to an important reason, and comparisons of survival in the same stage were not performed. Our results highlighted that survival improvement by time trend was accomplished in each stage (stage I-III), as well as in the overall population.

In the second part of our study analyzing survival outcome with breast cancer intrinsic subtypes, our data from a cohort with known intrinsic subtypes provided results similar to those of previous studies in which the triple-negative subtype showed the worst outcome.17,18,19 Furthermore, to isolate the prognostic influence of the subtype from the effect of tumor burden, we conducted survival analysis using the subtypes in stage I or stages II and III. In stages II and III, survival outcome significantly varied according to subtype. By contrast, in stage I, a significant difference was not observed in survival outcome among the subtypes, implying that the intrinsic subtypes less affect prognosis in early breast cancer. However, conflicting data have been reported that the subtypes play an important role in prognosis in early breast cancer,20,21 even in node-negative T1ab breast cancer.22 This discrepancy might be explained by the expanded use of chemotherapy in ER-negative patients because we actively used chemotherapy for ER-negative tumors, even for small tumors (data not shown). To solve contradictory results between our data and other studies, longer follow-up duration is required to delineate a survival pattern according to subtype because survival outcome in stage I is very favorable (the estimated 10-year OS rate is 90.9% in stage I).

The present retrospective study possesses several limitations. The retrospective design is associated with inherent limitations. The patients in our study, which is not based on clinical trials, showed heterogeneity in adjuvant therapy. The reasons contributing to survival improvement in each stage are not fully elucidated and the influence of advancement in adjuvant therapy could not be directly evaluated.

However, our findings have advantages over these limitations regarding the well-outlined survival improvement by time trend, and the unique analysis with the intrinsic subtypes based on a single-center database interfered less with heterogeneous treatment policies. The strengths of the study include a large patient population, the long-term follow up duration, and the uniform initial staging and follow-up surveillance protocol. Our attempt to ameliorate survival in Korean breast cancer patients will be facilitated by the findings that we were successful in improving outcome over time.

In conclusion, the present study provides significant evidence of improvement in the prognosis of Korean breast cancer patients with AJCC stage I-III during the recent 15 years, while considering the beneficial effect of significant prognostic factors. Our data imply that advancement of adjuvant treatment plays an integral part in producing a survival benefit and in expanding the therapeutic options for breast cancer patients. Moreover, we concordantly showed a clinical significance of the intrinsic subtypes and provided a novel insight regarding comparison of the prognostic impact between tumor burden and subtypes.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Kaplan-Meier plots for overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) according to the time period among patients with stage I-III disease. All p values are measured by the log-rank test. (A) OS (p<0.001). (B) RFS (p<0.001). |

| Fig. 2Kaplan-Meier plots for overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) according to the time period in each stage (I-III). All p values are measured by the log-rank test. (A) OS in stage I (p=0.002). (B) RFS in stage I (p=0.039). (C) OS in stage II (p<0.001). (D) RFS in stage II (p<0.001). (E) OS in stage III (p<0.001). (F) RFS in stage III (p<0.001). |

| Fig. 3Kaplan-Meier plots for overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) according to subtype. All p values are measured by the log-rank test. (A) OS by subtype in stages I-III (p=0.002). (B) RFS by subtype in stages I-III (p=0.039). (C) OS by subtype in stage I (p=0.517). (D) RFS in stage I (p=0.747). (E) OS by subtype in stages II-III (p=0.003). (F) RFS by subtype in stages II-III (p<0.001). HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We dedicated this study to Prof. Hy-De Lee, who largely contributed to establish the Koran Breast Cancer Society and improve in the management for Korean breast cancer patients. The authors also thank nurse Keum Son Jeung for help in the construction and management of database.

References

1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005; 55:74–108.

2. Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Boo YK, Shin HR, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality and survival in 2006-2007. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:1113–1121.

3. Lee JH, Yim SH, Won YJ, Jung KW, Son BH, Lee HD, et al. Population-based breast cancer statistics in Korea during 1993-2002: incidence, mortality, and survival. J Korean Med Sci. 2007; 22:Suppl. S11–S16.

4. The Korean Breast Cancer Society. Nationwide Korean Breast Cancer Data of 2004 Using Breast Cancer Registration Program. J Breast Cancer. 2006; 9:151–161.

5. Son BH, Kwak BS, Kim JK, Kim HJ, Hong SJ, Lee JS, et al. Changing patterns in the clinical characteristics of Korean patients with breast cancer during the last 15 years. Arch Surg. 2006; 141:155–160.

6. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat. 2013; 45:1–14.

7. Dawood S, Broglio K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Trends in survival over the past two decades among white and black patients with newly diagnosed stage IV breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:4891–4898.

8. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005; 365:1687–1717.

9. Trudeau M, Charbonneau F, Gelmon K, Laing K, Latreille J, Mackey J, et al. Selection of adjuvant chemotherapy for treatment of node-positive breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2005; 6:886–898.

10. Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, Goldhirsch A, Untch M, Smith I, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1659–1672.

11. Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, Suman VJ, Geyer CE Jr, Davidson NE, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1673–1684.

12. Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012; 490:61–70.

13. Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000; 406:747–752.

14. Singletary SE, Allred C, Ashley P, Bassett LW, Berry D, Bland KI, et al. Staging system for breast cancer: revisions for the 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Surg Clin North Am. 2003; 83:803–819.

15. Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer (unabridged version). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010; 134:e48–e72.

16. Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Thürlimann B, Senn HJ, et al. Strategies for subtypes-dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011; 22:1736–1747.

17. Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006; 295:2492–2502.

18. Lee JA, Kim KI, Bae JW, Jung YH, An H, Lee ES, et al. Triple negative breast cancer in Korea-distinct biology with different impact of prognostic factors on survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010; 123:177–187.

19. O'Brien KM, Cole SR, Tse CK, Perou CM, Carey LA, Foulkes WD, et al. Intrinsic breast tumor subtypes, race, and long-term survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2010; 16:6100–6110.

20. Park YH, Lee SJ, Cho EY, Choi YL, Lee JE, Nam SJ, et al. Clinical relevance of TNM staging system according to breast cancer subtypes. Ann Oncol. 2011; 22:1554–1560.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download