Abstract

Purpose

There are gaps between the treatment guideline and clinical practice of osteoporosis showing low compliance. Although attitude and knowledge of prescriber have been known to be associated with the low compliance in real clinical practice, no study has assessed the knowledge of prescriber regarding osteoporosis in accordance to the level of medical institution. We compared the knowledge on osteoporosis of general practitioners with that of practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital.

Materials and Methods

In May 2012, 40 general practitioners and 40 practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital were evaluated using a modified Facts on Osteoporosis Quiz.

Osteoporosis is a common and serious problem in the elderly population,1 and osteoporotic fractures are associated with decreased quality of life and excess mortality.2,3,4 Osteoporotic fractures could be prevented via osteoporosis treatment,5,6,7 which is recommended for elderly patients by evidence-based guidelines.8,9,10 However, there are gaps between the treatment guideline and clinical practice showing low compliance, especially in asymptomatic, chronic conditions like osteoporosis.11,12,13,14

Several factors, such as lack of awareness in physician or patients,13,15 adverse drug reactions (gastroesophaseal reflux and post-infusion syndrome),11,15,16,17,18 and subspecialty of prescriber19 have been known to be associated with low compliance. Among them, attitude and knowledge of the prescriber is associated with the low compliance in real clinical practice.15 Knowledge and awareness of the prescriber could be improved by educational programs.15 We hypothesized that knowledge on osteoporosis of the prescriber could be different according to the level of medical institution. However, little information is available concerning the knowledge of the prescriber for osteoporosis in accordance to the level of medical institution.

Recently, Facts on Osteoporosis Quiz (FOOQ) questionnaire is presented to assess knowledge of osteoporosis and it has been used in several studies because of a proven validity and reliability.20,21,22 The purpose of this study is to compare the knowledge on osteoporosis of general practitioners with that of practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital using FOOQ questionnaire.

The design and protocol of this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Sample size analysis was carried out to determine the minimum number of required patients by using the PS program (http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/wiki/Main/PowerSampleSize).23 The null hypothesis is that the level of knowledge would be similar between the general practitioners and practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital. Regarding the difference of 2 points or more in the mean score as significance, 36 subjects per group would be needed to achieve an alpha error of 0.05, at a power of 0.8, two-sided tails, and equal numbers in both groups. Assuming a 10% non-responder rate, we finally enrolled 40 subjects per group.

In May 2012, we recruited participants from Osteoporosis Symposium for the members of the Korean Hip Society held in Seoul. General practitioners were defined as physicians in clinic with 30 beds or less, and practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital were defined as physicians from tertiary hospitals with 300 beds or more. All participants were orthopedic surgeons. To evaluate the knowledge of osteoporosis, 40 general practitioners and 40 practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital were asked to answer a self-administered questionnaire, modified FOOQ24 before symposium.

FOOQ was based on the osteoporosis consensus conference of the National Institutes of Health in 200024 and consisted of 20 true and false questions. It has been reported to have a satisfactory validity and reliability.24 And it has been used to assess knowledge of osteoporosis.20,21,22 We modified 2 (item 10 and 15) among the 20 items, according to current epidemiologic information in Korean and recommendation of Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research.1 In modified item 10, the residual lifetime risk of osteoporotic fractures was about 60% in Korean women older than 50 years.1 In modified item 15, the recommendation of daily calcium intake was 1200 mg/day for the Korean population.1,25

We compared the score of this modified FOOQ between the general practitioners and practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital.

Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze the continuous variables, and Fisher's exact test to analyze the categorical values. Statistically significance was accepted for p-value of <0.05, and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

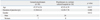

Thirty-eight of the 40 general practitioners and 38 of the 40 practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital completed the questionnaires (Table 1). Four practitioners, who did not reply all the questionnaires, were excluded.

Although the proportion of accurate answer to item 18 of practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital was higher than that of the general practitioners (92% vs. 71%, p=0.018), there was no significant difference in the total mean score between the two groups (p=0.386) (Table 2, Fig. 1).

The correct statement that "High-impact exercise improves bone health" (item 2) and the false statement that "Walking has a great impact on bone health" (item 14) was incorrectly identified by most of responders, regardless of the affiliation of the level of medical institution (Table 2).

Our finding presented that general practitioners have similar knowledge and understanding about osteoporosis, in comparison with the practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital. However, more practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital answered correctly in question about the effect of hormone replacement for osteoporosis. Although hormone replacement therapy was usually performed by obstetric and gynecologist in Korea, this study showed that orthopedic surgeons in a tertiary referral hospital had much knowledge about the hormone replacement therapy.

Most responders did not correctly answer the two items as previously specified (items 2 and 14), which were statements about the effect of physical exercise on osteoporosis, regardless of the affiliated medical institution (Fig. 1). By the 2000 NIH osteoporosis consensus conference, some evidence indicates that especially resistance and high-impact activities contribute to development of high peak bone mass.24 This could mean that almost orthopedic surgeons did not know the efficacy of exercise for osteoporosis, or that they underestimated the efficacy of exercise for osteoporosis in their practice. This exercise field of osteoporosis was revealed to be promoted at an educational program for clinical doctors.

Original FOOQ was developed in order to evaluate the knowledge of osteoporosis in patients or the general population and it consisted of 25 items. Based on the 2000 NIH osteoporosis consensus conference, modified FOOQ consisted of 20 true and false questions.24 Previous FOOQ studies on the general population reported that men have less knowledge about osteoporosis compared to women, who are prone to postmenopausal osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures.21,26 Further, it has been reported that the mean score (12.6±3.5) of the guardians of patients with hip fracture was lower than in the orthopedic doctors (16.7±1.8).22 The mean score of nurses in Singapore was 14.6±2.6 and the knowledge on osteoporosis of the nurses was different according to the level of work locations.20 However, no study has compared the knowledge of clinicians regarding osteoporosis, in accordance to the level of medical institution.

There were some limitations to our study. First, we applied FOOQ for the general population to clinical doctors. However, there was no validated questionnaire for clinicians, and modified FOOQ seems to be sufficient because we could find items with inadequate understanding by clinicians. Second, there might be selection bias of participants. It may fail to represent all clinicians at each level of medical institution. Third, there may be effects on result due to difference of characteristics of responders. In addition, older age and longer period of practice in general practitioners could influence our results.

In conclusion, our study showed that general practitioners have similar knowledge regarding the osteoporosis, compared to practitioners in a tertiary referral hospital, and that the effect of physical exercise should be stressed in an educational program on osteoporosis for practitioners.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Park C, Ha YC, Jang S, Jang S, Yoon HK, Lee YK. The incidence and residual lifetime risk of osteoporosis-related fractures in Korea. J Bone Miner Metab. 2011; 29:744–751.

2. Salaffi F, Cimmino MA, Malavolta N, Carotti M, Di Matteo L, Scendoni P, et al. The burden of prevalent fractures on health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: the IMOF study. J Rheumatol. 2007; 34:1551–1560.

3. Yoon HK, Park C, Jang S, Jang S, Lee YK, Ha YC. Incidence and mortality following hip fracture in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:1087–1092.

4. Lee YK, Jang S, Jang S, Lee HJ, Park C, Ha YC, et al. Mortality after vertebral fracture in Korea: analysis of the National Claim Registry. Osteoporos Int. 2012; 23:1859–1865.

5. Cranney A, Wells G, Willan A, Griffith L, Zytaruk N, Robinson V, et al. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. II. Meta-analysis of alendronate for the treatment of postmenopausal women. Endocr Rev. 2002; 23:508–516.

8. Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, Greenspan SL, Harris ST, Hodgson SF, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 2010; 16:Suppl 3. 1–37.

9. Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Hopkins R Jr, Forciea MA, Owens DK, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 149:404–415.

10. Dawson-Hughes B. National Osteoporosis Foundation Guide Committee. A revised clinician's guide to the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008; 93:2463–2465.

11. Seeman E, Compston J, Adachi J, Brandi ML, Cooper C, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Non-compliance: the Achilles' heel of anti-fracture efficacy. Osteoporos Int. 2007; 18:711–719.

12. Compston JE, Seeman E. Compliance with osteoporosis therapy is the weakest link. Lancet. 2006; 368:973–974.

13. Gong HS, Oh WS, Chung MS, Oh JH, Lee YH, Baek GH. Patients with wrist fractures are less likely to be evaluated and managed for osteoporosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009; 91:2376–2380.

14. Choi HJ, Shin CS, Ha YC, Jang S, Jang S, Park C, et al. Burden of osteoporosis in adults in Korea: a national health insurance database study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012; 30:54–58.

15. Kim SR, Ha YC, Park YG, Lee SR, Koo KH. Orthopedic surgeon's awareness can improve osteoporosis treatment following hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:1501–1507.

16. Lee YK, Nho JH, Ha YC, Koo KH. Persistence with intravenous zoledronate in elderly patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012; 23:2329–2333.

17. Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM. A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007; 18:1023–1031.

18. Kamatari M, Koto S, Ozawa N, Urao C, Suzuki Y, Akasaka E, et al. Factors affecting long-term compliance of osteoporotic patients with bisphosphonate treatment and QOL assessment in actual practice: alendronate and risedronate. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007; 25:302–309.

19. Rossini M, Bianchi G, Di Munno O, Giannini S, Minisola S, Sinigaglia L, et al. Determinants of adherence to osteoporosis treatment in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2006; 17:914–921.

20. Zhang RF, Chandran M. Knowledge of osteoporosis and its related risk factors among nursing professionals. Singapore Med J. 2011; 52:158–162.

21. Wilson RK, Tomlinson G, Stas V, Ridout R, Mahomed N, Gross A, et al. Male and non-English-speaking patients with fracture have poorer knowledge of osteoporosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011; 93:766–774.

22. Baek JH, Lee YK, Hong SW, Ha YC, Koo KH. Knowledge on osteoporosis in guardians of hip fracture patients. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013; 31:481–484.

23. Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990; 11:116–128.

24. Ailinger RL, Lasus H, Braun MA. Revision of the Facts on Osteoporosis Quiz. Nurs Res. 2003; 52:198–201.

25. Korea Women's Health and Osteoporosis Foundation. Korean Society of Osteoporosis. Korean Society of Gynecologic Endocrinology. Calcium and Vitamin D Recommendation. 2010.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download