Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to analyze the relationship between prostate volume and Gleason score (GS) upgrading [higher GS category in the radical prostatectomy (RP) specimen than in the prostate biopsy] in Korean men.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of 247 men who underwent RP between May 2006 and April 2011 at our institution. Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) volume was categorized as 25 cm3 or less (n=61), 25 to 40 cm3 (n=121) and greater than 40 cm3 (n=65). GS was examined as a categorical variable of 6 or less, 3+4 and 4+3 or greater. The relationship between TRUS volume and upgrading of GS was analyzed using multivariate logistic regression.

Results

Overall, 87 patients (35.2%) were upgraded, 20 (8.1%) were downgraded, and 140 (56.7%) had identical biopsy and pathological Gleason sum groups. Smaller TRUS volume was significantly associated with increased likelihood of upgrading (p trend=0.022). Men with prostates 25 cm3 or less had more than 2.7 times the risk of disease being upgraded relative to men with TRUS volumes more than 40 cm3 (OR 2.718, 95% CI 1.403-8.126).

At most urologic clinical centers, patients diagnosed as having prostate cancer are risk-stratified according to serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) level, findings on digital rectal examination and Gleason score (GS) on diagnostic biopsy.1 Urologists use these pre-treatment parameters to determine risk and counsel patients about treatment options.2 Of these parameters, GS on biopsy is a preeminent factor for decision making because it is usually best correlated with disease outcome. Especially, biopsy GS is used [in conjunction with clinical stage, PSA density (PSAD) and positive core percentage on biopsy] for predicting a clinically insignificant prostate cancer,3 which can be considered a target of active surveillance or watchful waiting rather than definite therapy.

However, since discrepancies in the GS from biopsy and from radical prostatectomy (RP) have been reported,4-9 numerous efforts have been made to identify preoperative factors for predicting GS discrepancy (especially, GS upgrading). To date, PSA, prostate volume, number of biopsy cores, obesity, number of positive cores on biopsy, and other factors have been reported4,6,7,10-15 as possible predictive factors for GS upgrading after RP.

A total of 247 patients who underwent RP under a diagnosis of prostate cancer from May 2006 to April 2011 at our institution were included in this study. Patients who received 5 alpha-reductase inhibitors, neoadjuvant androgen deprivation, chemotherapy or experimental agents that could affect the histological interpretation of the RP specimen were excluded. We also excluded patients who underwent biopsy with core numbers less than 12. We applied the prostate ellipsoid formula to assess prostate volume via transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) using a Voluson 530D ultrasound scanner with an SIC5-9 endfire endocavity probe (Kretz AG, Zipf, Austria). After obtaining measurements of prostate volume, the prostate was bilaterally biopsied near the base, mid-gland, and at the apex. All biopsy specimens were pathologically analyzed by at least two genitourinary pathologists who always gave a unified diagnosis after discussion following their independent reviews. For clinical staging, the 2002 tumor, node and metastasis (TNM) staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer was used. Open retropubic RP or robot-assisted laparoscopic RP was performed in all patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer. The RP specimen was sliced into 3 mm serial sections and deciphered by applying the same method of biopsy. The maximum GS on biopsy and RP specimens were compared. Upgrading of GS was defined as an elevation of the GS after surgery compared with TRUS biopsy. Similarly, downgrading was defined as RP GS in a lower category than biopsy GS.

After dividing our patients according to TRUS volume as 25 cm3 or less (n=61), 25 to 40 cm3 (n=121), or greater than 40 cm3 (n=65), we retrospectively analyzed the clinicopathologic data of the aforementioned subjects. GS was examined as a categorical variable of 6 or less, 3+4 and 4+3 or greater.

The distributions of baseline clinical and demographic characteristics across the three TRUS volume categories were compared using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. We used logistic regression to determine the odds ratios of upgrading relative to not upgrading for each TRUS volume group relative to the largest TRUS volume group. Multivariate analysis was performed to determine the independent risk of upgrading for each TRUS volume after controlling for confounding variables including age, body mass index (BMI), PSA, PSAD, presence of hypoechoic lesion on TRUS, and clinical stage. Using the same multivariate logistic regression models, adjusted mean risks of upgrading for Gleason 2-6 and Gleason 3+4 were computed for each TRUS category. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS program (version 15.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

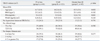

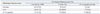

The medical records of a total of 247 patients were reviewed; 58 patients underwent open retropubic RP and 189 patients underwent robot-assisted RP. The baseline demographic and clinical features of patients in each TRUS volume category are presented in Table 1. Men with larger TRUS volumes were older (p=0.032) and had higher PSA (p=0.041) values. There were no significant differences in BMI (p=0.182), PSAD (p=0.320), number of hypoechoic lesion on TRUS (p=0.791), or clinical stage (p=0.590) across TRUS categories. Overall 87 patients (35.2%) were upgraded, 20 (8.1%) were downgraded, and 140 (56.7%) had identical biopsy and pathological Gleason sum groups. The distributions of biopsy and pathological GS are shown in Table 2.

In men with biopsy GSs 6 or less and 3+4 tumors, smaller volume prostates were more likely to be upgraded relative to larger prostates (p trend=0.038) (Table 3). After adjusting for multiple clinical features the likelihood of smaller volume prostates being upgraded became more pronounced (p trend=0.022). Men with prostates 25 cm3 or less had more than 2.7 times the risk of disease being upgraded relative to men with TRUS volumes more than 40 cm3 (OR 2.718, 95% CI 1.403-8.126).

When we select either active surveillance or watchful waiting for patients with prostate cancer, there must be the inherent assumption that the disease represented by the initial prostate biopsy is a true reflection of the disease extent within the prostate. However, any errors during determination of GS may lead to inappropriate surveillance of biologically aggressive tumors, or the selection of treatment options with inferior cure rates compared with other options. Furthermore, several reports6,10,18-22 have shown higher rates of capsular invasion, positive surgical margin, seminal vesicle invasion, lymphatic invasion, biochemical recurrence, or worse cancer-specific survival for patients who had GS upgrading. Thus, accurate grading is crucial in deciding treatment modalities for prostate cancer.19,23

Nevertheless, the rates of GS upgrading from biopsy Gleason score 6 diseases have been reported to be up to 30-50% after RP.4-7 To date, numerous predictive factors for GS upgrading after RP have been reported,4,6,7,10-15 including PSA, prostate volume, number of biopsy cores, obesity, and number of positive cores on biopsy. Of these, only a few studies7,13-15,24,25 examining prostate volume are available. Turley, et al.7 reported that men with prostates 20 cm3 or less had more than five times the risk of disease being upgraded relative to men with TRUS volumes more than 60 cm3, Kassouf, et al.13 reported that the incidence of tumor upgrading was significantly higher in patients with a prostate volume less than 50 cm3 compared to that in those with a larger prostate volume, and Moon, et al.14 found that prostate volume less than 36.5 cm3 was a predictive parameter for GS upgrading. In another report with a sample of Asian patients, Lim, et al.15 reported that men with prostates 30 cm3 or less had a greater than threefold risk of disease being upgraded relative to men with TRUS volumes more than 30 cm3.

Our results reconfirmed that small prostate volume was a predictor of GS upgrading after RP, as several authors showed.7,13-15 From our analysis, a cut-off prostate volume that was significantly associated with GS upgrading was 25 cm3. At first thought, larger (rather than smaller) prostates would be more likely to be upgraded after RP due to sampling error during biopsy. Moreover, it is well known that the Prostate Cancer Prevention Study raised hypothesis that the increased detection rate of high grade disease was due to superior sampling in patients with smaller glands after treatment with finasteride.7,15 Accordingly, our results conflict with such hypothesis.

Regarding the relationship between small prostate size and GS upgrading, we think that two possible factors play an important role, as several authors have suggested. First, lead-time biases in cancer detection might account for the relationship. Men with larger prostates tend to have increased PSA levels driven by benign prostatic hyperplasia, and therefore, are likely to be referred for prostate biopsy much sooner than other patients, leading to earlier cancer diagnoses, when well-differentiated prostate cancer is more likely.7,12,15,26 Secondly, smaller prostates might exhibit biologically more aggressive behavior and be associated with greater risk of progression.7,14,27

Several authors28,29 reported that PSAD was a powerful independent predictor of GS upgrading after RP. In our series, only preoperative PSA level and prostate volume were observed to be independent predictors for GS upgrading in multivariate logistic regression analysis (data not shown); PSAD was not an independent predictor for GS upgrading in our study, similar in another Korean report.10 Therefore, future study with more population will be needed, although this aspect does not diminish the significant message of this article.

In addition, we suggest that our result (regarding small prostate volume) would be regarded as an additory fact which supports the aggressiveness of prostate cancer in Korean men. As well known, prostate cancers arising in Korean men exhibit poor differentiation, regardless of the initial serum PSA level or clinical stage at presentation.30 Another aspect regarding the aggressiveness of prostate cancer in Korean men can be found in retrospective studies31,32 on the application of the Epstein criteria in Korean patients: Korean prostate cancer patients who fulfilled the Epstein criteria might not always behavior as clinically insignificant prostate cancer. Similary, Lee, et al.33 reported that 47% of patients were postoperatively found to have significant prostate cancer, even with a combination of four factors (biopsy GS ≤6, volume of the largest cancer <50%, PSAD ≤0.15 ng/mL/mL, and serum PSA ≤10 ng/mL).

There are several limitations to the present study. First, this study was conducted retrospectively at a single institute, and the study population was relatively small. Second, we did not examine the relationships between GS upgrading and factors such as PSA doubling time, free PSA, or number of positive cores on biopsy. Further large-scaled, prospective, multi-center studies are needed to confirm our results with increased statistical power.

In conclusion, our present study suggests that smaller prostate volumes might be a predictor of GS upgrading after RP. This should be kept in mind when making treatment decisions (such as active surveillance) for men with prostate cancer that appears to be of a low grade on biopsy. We think that our results have a significant clinical implication in Asian urologic fields, in that the prostate volumes of Asian patients are smaller than those of Westerners.

Figures and Tables

Table 3

Odds Ratios of Gleason Score Upgrading Based on Prostate Volume Category

TRUS, transrectal ultrasound; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Adjusted for biopsy Gleason score.

†Adjusted for age, body mass index, prostate specific antigen (PSA), PSA density, presence of hypoechoic lesion on TRUS, and clinical stage.

‡Computed by logistic regression model treating prostate volume as a logarithmic transformed continuous variable.

References

1. Corcoran NM, Hong MK, Casey RG, Hurtado-Coll A, Peters J, Harewood L, et al. Upgrade in Gleason score between prostate biopsies and pathology following radical prostatectomy significantly impacts upon the risk of biochemical recurrence. BJU Int. 2011; 108(8 Pt 2):E202–E210.

2. Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2005; 293:2095–2101.

3. Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, Brendler CB. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA. 1994; 271:368–374.

4. Kulkarni GS, Lockwood G, Evans A, Toi A, Trachtenberg J, Jewett MA, et al. Clinical predictors of Gleason score upgrading: implications for patients considering watchful waiting, active surveillance, or brachytherapy. Cancer. 2007; 109:2432–2438.

5. Gofrit ON, Zorn KC, Taxy JB, Lin S, Zagaja GP, Steinberg GD, et al. Predicting the risk of patients with biopsy Gleason score 6 to harbor a higher grade cancer. J Urol. 2007; 178:1925–1928.

6. Dong F, Jones JS, Stephenson AJ, Magi-Galluzzi C, Reuther AM, Klein EA. Prostate cancer volume at biopsy predicts clinically significant upgrading. J Urol. 2008; 179:896–900.

7. Turley RS, Hamilton RJ, Terris MK, Kane CJ, Aronson WJ, Presti JC Jr, et al. Small transrectal ultrasound volume predicts clinically significant Gleason score upgrading after radical prostatectomy: results from the SEARCH database. J Urol. 2008; 179:523–527.

8. Hsieh TF, Chang CH, Chen WC, Chou CL, Chen CC, Wu HC. Correlation of Gleason scores between needle-core biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens in patients with prostate cancer. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005; 68:167–171.

9. Nepple KG, Wahls TL, Hillis SL, Joudi FN. Gleason score and laterality concordance between prostate biopsy and prostatectomy specimens. Int Braz J Urol. 2009; 35:559–564.

10. Hong SK, Han BK, Lee ST, Kim SS, Min KE, Jeong SJ, et al. Prediction of Gleason score upgrading in low-risk prostate cancers diagnosed via multi (> or = 12)-core prostate biopsy. World J Urol. 2009; 27:271–276.

11. Miyake H, Kurahashi T, Takenaka A, Hara I, Fujisawa M. Improved accuracy for predicting the Gleason score of prostate cancer by increasing the number of transrectal biopsy cores. Urol Int. 2007; 79:302–306.

12. Freedland SJ, Kane CJ, Amling CL, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Presti JC Jr. SEARCH Database Study Group. Upgrading and downgrading of prostate needle biopsy specimens: risk factors and clinical implications. Urology. 2007; 69:495–499.

13. Kassouf W, Nakanishi H, Ochiai A, Babaian KN, Troncoso P, Babaian RJ. Effect of prostate volume on tumor grade in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy in the era of extended prostatic biopsies. J Urol. 2007; 178:111–114.

14. Moon SJ, Park SY, Lee TY. Predictive factors of Gleason score upgrading in localized and locally advanced prostate cancer diagnosed by prostate biopsy. Korean J Urol. 2010; 51:677–682.

15. Lim T, Park SC, Jeong YB, Kim HJ, Rim JS. Predictors of Gleason score upgrading after radical prostatectomy in low-risk prostate cancer. Korean J Urol. 2009; 50:1182–1187.

16. Mochtar CA, Kiemeney LA, van Riemsdijk MM, Barnett GS, Laguna MP, Debruyne FM, et al. Prostate-specific antigen as an estimator of prostate volume in the management of patients with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2003; 44:695–700.

17. Chung BH, Hong SJ, Cho JS, Seong DH. Relationship between serum prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume in Korean men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a multicentre study. BJU Int. 2006; 97:742–746.

18. Müntener M, Epstein JI, Hernandez DJ, Gonzalgo ML, Mangold L, Humphreys E, et al. Prognostic significance of Gleason score discrepancies between needle biopsy and radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008; 53:767–775.

19. Moussa AS, Li J, Soriano M, Klein EA, Dong F, Jones JS. Prostate biopsy clinical and pathological variables that predict significant grading changes in patients with intermediate and high grade prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2009; 103:43–48.

20. Pinthus JH, Witkos M, Fleshner NE, Sweet J, Evans A, Jewett MA, et al. Prostate cancers scored as Gleason 6 on prostate biopsy are frequently Gleason 7 tumors at radical prostatectomy: implication on outcome. J Urol. 2006; 176:979–984.

21. Humphrey PA, Frazier HA, Vollmer RT, Paulson DF. Stratification of pathologic features in radical prostatectomy specimens that are predictive of elevated initial postoperative serum prostate-specific antigen levels. Cancer. 1993; 71:1821–1827.

22. Zincke H, Bergstralh EJ, Blute ML, Myers RP, Barrett DM, Lieber MM, et al. Radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: long-term results of 1,143 patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 1994; 12:2254–2263.

23. Carter HB, Allaf ME, Partin AW. Diagnosis and staging of prostate cancer. In : Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Norvick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. 2007. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders WB;p. 2912–2931.

24. Davies JD, Aghazadeh MA, Phillips S, Salem S, Chang SS, Clark PE, et al. Prostate size as a predictor of Gleason score upgrading in patients with low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011; 186:2221–2227.

25. Mir MC, Planas J, Raventos CX, de Torres IM, Trilla E, Cecchini L, et al. Is there a relationship between prostate volume and Gleason score? BJU Int. 2008; 102:563–565.

26. Kojima M, Troncoso P, Babaian RJ. Influence of noncancerous prostatic tissue volume on prostate-specific antigen. Urology. 1998; 51:293–299.

27. Freedland SJ, Isaacs WB, Platz EA, Terris MK, Aronson WJ, Amling CL, et al. Prostate size and risk of high-grade, advanced prostate cancer and biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy: a search database study. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:7546–7554.

28. Magheli A, Hinz S, Hege C, Stephan C, Jung K, Miller K, et al. Prostate specific antigen density to predict prostate cancer upgrading in a contemporary radical prostatectomy series: a single center experience. J Urol. 2010; 183:126–131.

29. Sfoungaristos S, Perimenis P. Clinical and pathological variables that predict changes in tumour grade after radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012; 1–5.

30. Song C, Ro JY, Lee MS, Hong SJ, Chung BH, Choi HY, et al. Prostate cancer in Korean men exhibits poor differentiation and is adversely related to prognosis after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2006; 68:820–824.

31. Lee SE, Kim DS, Lee WK, Park HZ, Lee CJ, Doo SH, et al. Application of the Epstein criteria for prediction of clinically insignificant prostate cancer in Korean men. BJU Int. 2010; 105:1526–1530.

32. Yeom CD, Lee SH, Park KK, Park SU, Chung BH. Are clinically insignificant prostate cancers really insignificant among Korean men? Yonsei Med J. 2012; 53:358–362.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download