Abstract

Purpose

Despite the ready availability of pneumococcal vaccine, vaccination rates are quite low in South Korea. This study was designed to assess perceptions and awareness about pneumococcal vaccines among subjects at risk and find strategies to increases vaccine coverage rates.

Materials and Methods

A cross sectional, community-based survey was conducted to assess perceptions about the pneumococcal vaccine at a local public health center. In a tertiary hospital, an outpatient-based pneumococcal vaccine campaign was carried out for the elderly and individuals with chronic co-morbidities from May to July of 2007.

Results

Based on the survey, only 7.6% were ever informed about pneumococcal vaccination. The coverage rates of the pneumococcal vaccine before and after the hospital campaign showed an increased annual rate from 3.39% to 5.91%. The most common reason for vaccination was "doctor's advice" (53.3%). As for the reasons for not receiving vaccination, about 75% of high risk patients were not aware of the pneumococcal vaccine, which was the most important barrier to vaccination. Negative clinician's attitude was the second most common cause of non-vaccination.

Invasive pneumococcal disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly in individuals with chronic co-morbidities and in those older than 65 years of age. Despite appropriate antibiotic therapy and supportive care, there is a higher case fatality rate from pneumococcal bacteremia in these high-risk adults (15-20%) than in healthy individuals aged 16-64 years (5.4%).1

There is evidence supporting the efficacy of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23vPPV) against invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in adults; prior vaccination against pneumococcus is associated with improved survival and decreased risks of respiratory failure and other complications.2,3 The United States Public Health Service has worked to enhance pneumococcal vaccination rates through a program called Healthy People 2010, that aims to immunize 90% of the elderly (65 years and older) and 60% of younger high risk individuals against pneumococcal diseases.4 Despite the ready availability of effective pneumococcal vaccines, vaccination rates around the world have remained suboptimal. In South Korea, only 46.8% of physicians recommend pneumococcal vaccination for high-risk individuals, and only 0.6% of high-risk patients replied that they were encouraged to get the pneumococcal vaccine according to a nation-wide survey (unpublished data).

In this study, we estimated pneumococcal vaccine coverage rates, awareness, and perceptions among elderly individuals and individuals with chronic medical conditions. The same questionnaire survey was performed in both public health center and tertiary teaching hospital to see if there were some differences according to clinical setting. Secondly, we investigated the effects of a hospital campaign program that was intended to raise the pneumococcal vaccination rate in an outpatient setting at a tertiary teaching hospital.

In May 2007, a cross sectional, community-based survey was conducted at a local public health center located in southwestern Seoul, Korea to assess perceptions and awareness about pneumococcal vaccines; questionnaires were distributed to subjects older than 50 years. The 16-item, self-administered questionnaire contained questions about the demographic characteristics of the respondents and about motivating and interrupting factors influencing immunization and vaccination status.

At the Korea University Guro Hospital (KUGH), an outpatient-based pneumococcal vaccine campaign was undertaken targeting high risk outpatients (older than 65 years, malignancy, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, chronic cardiovascular disease, chronic renal disease, chronic lung disease or connective tissue disease) from May to July of 2007. During the three month campaign period, the following institution-wide measures were applied: as for the patients, 1) operation of an active information desk for the initial two weeks, 2) display of color posters and informational brochures highlighting the key messages and places to receive immunization and 3) provision of open classes for patients and their family members; as for the physicians, 1) circulation of a newsletter describing the indications for and efficacy of pneumococcal vaccine and 2) conducting pneumococcal vaccine seminars for those who treat high risk patients. Before and after the campaign, the pneumococcal vaccine coverage rate among high risk outpatients was assessed and compared by estimating the number of individuals who had been vaccinated (pre-campaign period from May 2006 to April 2007 versus post-campaign period from May 2007 to April 2008). In each period, previously vaccinated subjects were excluded from the denominator. In April 2007 (initial survey before the campaign) and September 2007 (follow-up survey after the campaign), an 11-item (physician) and the aforementioned 16-item (patient) questionnaires were randomly distributed. The 16-item patient questionnaire was identical to that of the community-based survey, and the 11-item physician questionnaire contained questions about the physician's knowledge of pneumococcal vaccine indication, interrupting factors of respondents' recommendations regarding vaccination, factors that encouraged doctors to recommend vaccination, and commonly-used information sources.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of KUGH and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice.

SPSS software version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to compare the results of pre- and post-campaign period assessments. Categorical variables were analyzed using either a chi-square test or a Fisher's exact test. All tests for significance were two-tailed; p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Among a total of 500 respondents at the public health center, 370 subjects (74%) were high-risk patients indicated for pneumococcal vaccination, based on Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations: elderly subjects aged ≥65 years (266, 53.2%), cardiovascular disease (248, 49.6%), diabetes (72, 14.4%), connective tissue disease (39, 7.8%), chronic liver disease (7, 1.4%), chronic lung disease (3, 0.6%), malignancy (2, 0.4%) and chronic renal disease (1, 0.2%). However, only 38 (7.6%) of the 500 respondents had ever been informed of the pneumococcal vaccine, and none had been vaccinated previously. Therefore, further statistical analysis could not be undertaken. At KUGH, the annual coverage rates of pneumococcal vaccine increased from 3.39% before the hospital campaign (422 among 12460 patients) to 5.91% after the hospital campaign (744 among 12591 patients) (Table 1). Compared to the subjects of the public health center, the proportion of malignancy, diabetes and chronic liver diseases were higher in those of KUGH, while the proportions of elderly subjects and cardiovascular diseases were the opposite. Although pneumonia occurs throughout the year in Korea, the pneumococcal vaccine is usually administered during autumn (September-November). Of note, the rate of pneumococcal vaccination doubled (from 104 doses to 226 doses) in September immediately after the 2007 campaign, compared to the same period in the previous year (Fig. 1). When we analyzed the vaccination rate in detail according to age and underlying diseases, the increments of pneumococcal vaccine coverage rate were statistically significant in patients with either chronic lung disease or chronic renal disease (p<0.01) (Fig. 2). As for patients with connective tissue disease, the coverage rate was high even before the campaign; after the campaign, the rate increased from 53.8% to 62.3% (p=0.03). In comparison, vaccine coverage rates among patients with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, malignancy or chronic liver diseases were still extremely low after the campaign.

Of the total responses from 451 KUGH outpatients, 21 insincere responses were excluded and, therefore, data from 430 outpatients were analyzed. The mean age of all respondents was 55.7±13.5 years, with the total sample including 201 (46.7%) men and 131 (30.5%) women aged ≥65 years. Among the 430 respondents, only 15 (3.5%) had received the pneumococcal vaccination. The reasons given for receiving vaccinations among the 15 vaccinees are described in Table 2. The most common reason for vaccination was "doctor's advice" (53.3%), followed by "having chronic diseases" (33.3%), "previous experience of pneumonia" (20%), "to prevent pneumonia as well as the common cold" (20%) and "recommendations from friends or relatives" (20%). As for the factors that impeded respondents who might otherwise have sought pneumococcal vaccination, more than 75% of non-vaccinees replied that "I was not informed of pneumococcal vaccine by doctors or other people" during both the pre- and post-campaign periods (Table 3). Compared to the pre-campaign period, more non-vaccinees in the post-campaign period replied that they did not receive the pneumococcal vaccine because their doctors did not advise them to get it. "No previous experience of pneumococcal vaccination" (12.5%) and "self perception of good health" (12.3%) were ranked as the third and fourth most common causes of non-vaccination, respectively.

As for the survey of doctors, the questionnaire was distributed to 55 physicians, and the reception rate was 81.8% (n=45) in the pre-campaign period and 54.5% (n=30) in the post-campaign period. The results of the KUGH survey for doctors showed that most doctors were well aware of the indications for the pneumococcal vaccine before the campaign began (Table 4). As for barriers to recommending pneumococcal vaccination, "distrust of vaccine efficacy" was markedly decreased after the campaign (p<0.01), but "low needs (demand) from patients" and "troublesome to explain the usefulness of the pneumococcal vaccine" were still common responses. Doctors usually obtain information about vaccines at medical symposia/conferences or from colleagues. After the pneumococcal vaccine campaign, the doctors whom we surveyed were more likely to report that they had obtained information about vaccines from campaign brochures (p<0.01) and medical journals (p=0.02). The effects of mass media and information by manufacturers were minimal. As for factors that increased the frequency of prescription of the pneumococcal vaccine, doctors ranked "proven data on vaccine efficacy", "guidelines of expert associations", "advertisement via mass media by government and health departments" and "cheap cost of vaccine", in that order (Fig. 3).

Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) causes invasive infections including meningitis, pneumonia with parapneumonic effusion and bacteremia, especially in individuals aged ≥65 years and those with chronic medical conditions. Despite the ready availability of vaccines and antibiotics, the World Health Organization reported that S. pneumoniae is responsible for approximately 1.6 million deaths annually.5 Vaccination is a cost-effective means to prevent IPD, but vaccine coverage rates remain suboptimal. Although some European countries have reported higher coverage rates for the pneumococcal vaccine (around 50%) among high risk populations, most countries do not even report these rates, and those that do, typically report lower rates than their rates of influenza vaccination.6-8 Likewise, in South Korea, influenza vaccine coverage in high risk groups was over 60%.9 Conversely, this study showed that the pneumococcal vaccine coverage was less than 5% among high risk patients at a tertiary teaching hospital, and the rate was actually zero among subjects who responded to a community-based survey.

The ACIP recommends concurrent administration of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines to inpatients at discharge as a strategy for increasing vaccination coverage among adults. According to the surveys by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 20% of persons aged ≥65 years who said they received influenza vaccines reported never having received a pneumococcal vaccination, indicating missed opportunities for pneumococcal vaccine administration at the time of influenza vaccination.10,11 Previously, many in-hospital campaigns have focused on the pneumococcal vaccination of high risk inpatients prior to discharge using computerized reminders, standing order programs, or pre-printed order programs.12,13 Although such strategies might be effective in improving pneumococcal vaccine coverage, a more diverse approach is needed to cover the large population of high risk individuals who are not hospitalized. A greater number of opportunities to vaccinate high risk subjects may be presented in outpatient clinic settings.14 This is, to our knowledge, the first study addressing the efficacy of an outpatient-based pneumococcal vaccine campaign. In this study, we found that a three-month, brief, outpatient-based campaign early in the influenza season was quite effective in increasing pneumococcal vaccination. If conducted annually early in the influenza season, short-term pneumococcal vaccine campaigns may be effective in improving vaccine coverage rates among high risk adults. Of note, although the current outpatient-based campaign effectively increased pneumococcal vaccination in patients with either chronic lung disease or chronic renal disease, its results were unremarkable in patients with diabetes, chronic liver disease or malignancy, suggesting that targeted campaigns may be more effective for some patient populations.

Many barriers to achieving high pneumococcal vaccination levels have previously been identified, including missed opportunities, competing demand, pitfalls in the vaccine delivery system, fears regarding adverse effects, and lack of awareness regarding the seriousness of IPD.10,15 In the present study, we evaluated encouraging factors and barriers of pneumococcal vaccination in Korea, a country with low vaccine coverage rates. According to the results of the present study, the most important barrier to pneumococcal vaccination was that 75% of high risk patients were not even aware that the vaccine existed. The second most common barrier to vaccination was a negative attitude on the part of clinicians. However, advice from doctors was the most important factor that encouraged subjects to obtain vaccinations, similar to results previously published in numerous studies, even for other vaccines.16-19 While clinician distrust of the efficacy of the pneumococcal vaccine was markedly improved after the hospital campaign, most were still unwilling to prescribe pneumococcal vaccines due to the low levels of awareness of the vaccine among patients and lack of direct requests from patients. In fact, even when they did prescribe pneumococcal vaccines, doctors typically did not spend much time or effort educating patients about it. Most of the clinicians surveyed thought that patient education should be enhanced through diverse strategies: guidelines from expert associations, advertisements via mass media, or cheaper vaccine costs.

In conclusion, we found that knowledge of and immunization rates against pneumococcal disease were low in South Korea. Annual outpatient-based campaigns early in the influenza season may be effective in improving pneumococcal vaccine coverage rates. As shown in this study, a doctor's advice was the most important factor influencing whether or not patients indicated for vaccination actually sought after vaccination; however, government and health departments should make greater efforts to improve patients' perception and knowledge regarding pneumococcal diseases and vaccination.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Monthly number of pneumococcal vaccinations for the high risk population of a tertiary teaching hospital: a comparison between pre-campaign (May 2006-April 2007) and post-campaign (May 2007-April 2008) periods.

Fig. 2

Pneumococcal vaccine coverage rates (number of vaccinees) for the high risk population of a tertiary teaching hospital, classified according to age and chronic medical conditions; connective tissue diseases include systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases requiring the use of either steroids or immunosuppressants. *p<0.01, †p=0.03.

Fig. 3

Doctor encouraging factors (%) for the prescription of pneumococcal vaccine at a tertiary teaching hospital (total no.=75); each doctor ranked three high priorities in sequence.

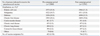

Table 1

Distribution of High Risk Population and Coverage Rates of Pneumococcal Vaccination in the Pre- and Post-Campaign Periods: a Tertiary Teaching Hospital-Based Survey

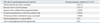

Table 2

Reasons for Pneumococcal Vaccination among the High Risk Vaccinees of a Tertiary Teaching Hospital

References

1. Thomas CM, Loewen A, Coffin C, Campbell NR. Improving rates of pneumococcal vaccination on discharge from a tertiary center medical teaching unit: a prospective intervention. BMC Public Health. 2005. 5:110.

2. Mykietiuk A, Carratalà J, Domínguez A, Manzur A, Fernández-Sabé N, Dorca J, et al. Effect of prior pneumococcal vaccination on clinical outcome of hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006. 25:457–462.

3. Greene CM, Kyaw MH, Ray SM, Schaffner W, Lynfield R, Barrett NL, et al. Preventability of invasive pneumococcal disease and assessment of current polysaccharide vaccine recommendations for adults: United States, 2001-2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2006. 43:141–150.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010. 2000. Conference ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services.

5. Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Bassani DG, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010. 375:1969–1987.

6. Jiménez-García R, Ariñez-Fernandez MC, Hernández-Barrera V, Garcia-Carballo MM, de Miguel AG, Carrasco-Garrido P. Compliance with influenza and pneumococcal vaccination among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease consulting their medical practitioners in Catalonia, Spain. J Infect. 2007. 54:65–74.

7. Vila-Córcoles A, Ochoa-Gondar O, Ester F, Sarrá N, Ansa X, Saún N. EVAN Study Group. Evolution of vaccination rates after the implementation of a free systematic pneumococcal vaccination in Catalonian older adults: 4-years follow-up. BMC Public Health. 2006. 6:231.

8. Andrews RM. Assessment of vaccine coverage following the introduction of a publicly funded pneumococcal vaccine program for the elderly in Victoria, Australia. Vaccine. 2005. 23:2756–2761.

9. Kee SY, Lee JS, Cheong HJ, Chun BC, Song JY, Choi WS, et al. Influenza vaccine coverage rates and perceptions on vaccination in South Korea. J Infect. 2007. 55:273–281.

10. Greci LS, Katz DL, Jekel J. Vaccinations in pneumonia (VIP): pneumococcal and influenza vaccination patterns among patients hospitalized for pneumonia. Prev Med. 2005. 40:384–388.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination coverage among persons aged > or = 65 years--United States, 2004-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006. 55:1065–1068.

12. Vondracek TG, Pham TP, Huycke MM. A hospital-based pharmacy intervention program for pneumococcal vaccination. Arch Intern Med. 1998. 158:1543–1547.

13. Nichol KL, Zimmerman R. Generalist and subspecialist physicians' knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations for elderly and other high-risk patients: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med. 2001. 161:2702–2708.

14. Kyaw MH, Greene CM, Schaffner W, Ray SM, Shapiro M, Barrett NL, et al. Adults with invasive pneumococcal disease: missed opportunities for vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2006. 31:286–292.

15. Kempe A, Hurley L, Stokley S, Daley MF, Crane LA, Beaty BL, et al. Pneumococcal vaccination in general internal medicine practice: current practice and future possibilities. J Gen Intern Med. 2008. 23:2010–2013.

16. Kaufman Z, Green MS. Compliance with influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations in Israel, 1999-2002. Public Health Rev. 2003. 31:71–79.

17. Müller D, Szucs TD. Influenza vaccination coverage rates in 5 European countries: a population-based cross-sectional analysis of the seasons 02/03, 03/04 and 04/05. Infection. 2007. 35:308–319.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download