Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to study the appropriate cut-off value of visceral fat area (VFA) and waist-to-height ratio (WTHR) which increase the risk of obesity-related disorders and to validate the diagnostic criteria of abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome in Korean children and adolescents.

Materials and Methods

A total 314 subjects (131 boys and 183 girls) were included in this study. The subjects were selected from Korean children and adolescents who visited three University hospitals in Seoul and Uijeongbu from January 1999 to December 2009. All patients underwent computed tomography to measure VFA.

Results

The cut-off value of VFA associated with an increase risk of obesity-related disorder, according to the receiver operating characteristics curve, was 68.57 cm2 (sensitivity 59.8%, specificity 76.6%, p=0.01) for age between 10 to 15 years, and 71.10 cm2 (sensitivity 72.3%, specificity 76.5%, p<0.001) for age between 16 to 18 years. By simple regression analysis, the WTHR corresponding to a VFA of 68.57 cm2 was 0.54 for boys and 0.61 for girls, and the WTHR corresponding to a VFA of 71.10 cm2 was 0.51 for boys and 0.56 for girls (p=0.004 for boys, p<0.001 for girls).

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, VFA which increases the risk of obesity-related disorders was 68.57 cm2 and the WTHR corresponding to this VFA was 0.54 for boys and 0.61 for girls age between 10-15 years, 71.70 cm2 and the WTHR 0.51 for boys and 0.56 for girls age between 16-18 years. For appropriate diagnostic criteria of abdominal obesity and obesity-related disorders in Korean children and adolescents, further studies are required.

It is well known that the obese population is increasing globally, and obesity in particular is increasing in children and adolescents.1 Obesity in children and adolescents is known to easily progress to adult obesity, and to increase the risks of hypertension, type II diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.2,3

The body mass index (BMI) is commonly used to evaluate obesity. It has the disadvantage, however, of being unable to figure out the degree of abdominal obesity, which is a risk factor of obesity-related diseases.4 Furthermore, as the growth rate of children and adolescents varies depending on their age and gender, it is difficult to suggest a standard reference.

Various indices, including the waist circumference, the waist hip ratio (WHR), the abdominal sagital diameter, and fat measurement with ultrasonography, CT, and MRI have been used to measure obesity. In 1998, the World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledged that the waist circumference is a more accurate index of abdominal obesity than WHR.5 In addition, the visceral fat area, measured with CT, is well known to most accurately reflect abdominal obesity.6,7 Accordingly, the use of the visceral fat area as reference for abdominal obesity has been proposed.8,9 Based on the aforementioned facts, the waist circumference has been used to diagnose metabolic syndrome. In 2007, the International Diabetes Association suggested the criteria for diagnosing pediatric metabolic syndrome, which were modified from the adult criteria based on age.10 It is quite cumbersome, however, to follow the new criteria, as they require the calculation of the waist circumference percentile according to the standard growth graph. In addition, several recent studies reported that the waist-to-height ratio is more accurate than the waist circumference in measuring the risks of obesity-related diseases.11,12

This study was conducted to measure the cut-off value of the visceral fat area that increases the risk of obesity-related diseases in Korean children and adolescents, and to calculate the cut-off value of the waist-to-height ratio that can be easily applied to clinical practice using the cut-off value of the visceral fat area.

Among children and adolescents who visited obesity clinics of three university hospitals in Seoul and Gyeonggi province from 1998 to 2009, 336 applicants (142 boys and 194 girls) who underwent visceral fat measurement with CT were screened. Those who had obesity-causing diseases and severe liver and kidney diseases were excluded from the study. Girls who had history of using oral contraceptive were also excluded. Finally, a total of 314 subjects (131 boys and 183 girls) were included. All the subjects completed an informed consent form before participating in the study, and the study was conducted after the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the School of Medicine of The Catholic University of Korea.

The subjects' height and weight were measured with a body-measuring device and an automatic balancer while the subjects were wearing light clothes. As for the waist circumference, the thinnest area between the inferior part of the lowest rib and the iliac crest was measured in cm. The systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured twice with an automatic blood pressure monitor after a stable condition for at least 10 minutes, and the mean value was used.

The areas of subcutaneous fat and visceral fat were calculated with a computer installed in a CT after the level of the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebra was scanned with a CT (Somatom Plus, Siemens, Germany). A protection device made of lead was used to minimize the exposure to X-ray during CT scan.

The fasting blood sugar; the total cholesterol and triglycerides; and the high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were measured after collecting blood samples in a 12-hour fasting condition.

As for the criteria for metabolic syndrome, the criteria for pediatric metabolic syndrome that were suggested by the International Diabetes Association in 2007 were used.10 As for the criteria for obesity-related diseases, the following criteria were used, except for the waist circumference, because the purpose of this study was to analyze the waist circumference that increases the risks of obesity-related diseases.

1) Waist circumference of 90 percentile or higher based on age and gender according to the revised version of the standard growth graph in Korean children and adolescents (2007)

2) Triglycerides of 150 mg/dL or higher

3) High-density cholesterol of less than 40 mg/dL (for both male and female)

4) Systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or higher, or diastolic blood pressure of 85 mm Hg or higher

5) Fasting blood sugar of 100 mg/dL or higher

According to the criteria for pediatric metabolic syndrome proposed by the International Diabetes Association in 2007, the criteria for people aged 16 years and older were identical with the adult criteria for metabolic syndrome. In this study, the criteria for modified Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) (2005), which added to the aforementioned criteria the diagnosis criteria for abdominal obesity in Asians suggested by the West Pacific Office of WHO (2000) based on the National Cholesterol Education Program ATP III (2001), were used.13 As for the criteria for obesity-related diseases, the following criteria were used, except for the waist circumference, for the same reason as that mentioned previously.

1) Waist circumference >90 cm (boys), >80 cm (girls)

2) Triglycerides of 150 mg/dL or higher

3) High-density cholesterol of less than 40 mg/dL (boys), 50 mg/dL (girls)

4) Systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or higher, or diastolic blood pressure of 85 mm Hg or higher

5) Fasting blood sugar of 100 mg/dL or higher

SPSS for Windows Version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., USA) was used for the statistical analysis. The characteristics of the subjects based on sex were investigated using the t-test. The relative risk of metabolic syndrome was investigated based on the BMI and the visceral fat area. As for the visceral fat area that increases the risk of obesity-related diseases, after setting specificity on the horizontal axis and sensitivity on the vertical axis, the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was drawn, and the best cut-off point was obtained as the highest sum of the sensitivity and specificity values. In addition, the waist-to-height ratio that corresponded to the visceral fat area that increases the risk of obesity-related diseases was calculated via simple regression analysis. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

The mean BMI of all the subjects was 30.82±4.1 kg/m2, which shows a more obese condition than that of the general group. No significant differences in the diastolic blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, and abdominal subcutaneous fat were found between boys and girls. All the other indices, however, except for HDL-cholesterol, were significantly higher in boys than in girls (p<0.05) (Table 1). No significant differences in the systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, and HDL-cholesterol were found between the group aged 16 years and higher and the group aged less than 16 years. The visceral fat area was higher in the group aged 16 years and higher, as expected. On the other hand, no significant differences in the waist-to-height ratio and the visceral fat area/subcutaneous fat area ratio were found, based on age (Table 2).

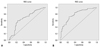

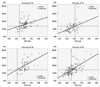

The ROC curve was analyzed after classifying the total subjects into the group aged 10-15 years and the group aged 16 years and higher. The cut-off value of the visceral fat area that increases the risks of obesity-related diseases was 68.57 cm2 (sensitivity 59.8%, specificity 76.6%, p=0.01) in the group aged 10-15 years, and 71.10 cm2 (sensitivity 72.3%, specificity 76.5%, p<0.001) in the group aged 16 years and higher (Fig. 1). Based on these results, the waist-to-height ratio that corresponded to the cut-off value of the visceral fat area that increases the frequency of obesity-related diseases was calculated via simple regression analysis. It was 0.54 in boys and 0.61 in girls in the group aged 10-15 years, whereas it was 0.51 in boys and 0.56 in girls in the group aged 16 years and higher (p<0.005) (Fig. 2).

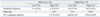

Of all the subjects, 98 (31.2%) had no obesity-related diseases and 102 (32.5%) had one obesity-related disease, whereas 114 (36.3%) had at least two obesity-related diseases. When the subjects were classified into four groups based on a BMI of 30 and the visceral fat area (10-15 years <68.57cm2, 16 years and higher <71.10 cm2), the frequency of obesity-related diseases of the groups showed statistical significance (p<0.001) (Table 3).

Of all the subjects, 105 (33.4%) had metabolic syndrome,10 of which 54 (41.2%) were boys and 51 (27.9%) were girls. When the relative risk of each risk factor based on the group with the lower BMI and smaller visceral fat area (BMI<30,visceral fat area: 10-15 years <68.57 cm2, 16 years or higher <71.10 cm2), the odds ratio of metabolic syndrome based on the differences in the BMI and the visceral fat area showed a statistically significant increase (Table 4).

Although several studies have reported that the visceral fat area is associated with the risk of obesity-related diseases in children and adolescents,14,15 no study has suggested a detailed reference value. Direct measurement of the visceral fat area is the most accurate way to predict the risk of obesity-related diseases. It is, however, difficult to implement in clinical practice. Therefore, it is important to establish indices and reference values that can easily predict the risk of obesity-related diseases. Furthermore, it is cumbersome to apply the conventional BMI or waist circumference to children and adolescents, because the conversion process via the standard growth graph is required. Furthermore, recent studies have reported that the waist-to-height ratio is more accurate than the BMI or the waist circumference.16,17

McCarthy suggested17 that the cut-off value of the waist-to-height ratio should be 0.5. Another study on Chinese children and adolescents suggested12 0.445 and 0.485 as the cut-off values for an overweight condition and for obesity, respectively, which show significant discrepancies with the values obtained in the present study. This is likely due to the fact that the focus of the previous studies was the diagnosis of obesity and an overweight condition, whereas the risk of obesity-related diseases was the focus of this study. According to a recent study that compared the visceral fat and the waist-to-height ratio via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry,18 the waist-to-height ratio was more accurate than the other indices. Regardless of gender and age, the aforementioned study suggested the cut-off value of 0.54, which was closer to the results of this study than the cut-off values suggested by the previous studies.

In this study, the cut-off value of the waist-to-height ratio was higher in girls than in boys, and was higher as the subject was younger. This result is likely due to higher waist circumference that corresponded to the same amount of the visceral fat area in girls than in boys, and is similar to the results of a previous study on adults.8,9 As shown in the characteristics of the subjects, the visceral fat area/subcutaneous fat area ratio (VSR) was lower in girls than in boys, which means that the subcutaneous fat ratio was higher in girls than in boys. In adults, this result is known to be due to the effect of female hormones. More comprehensive studies are required to determine if this result was caused by female hormones19 in children and adolescents.

In addition, there are two possibilities with respect to the higher cut-off value of the waist-to-height ratio as the subject was younger. First, obesity-related diseases seems to be hard to occur at a young age. Second, the waist-to-height ratio becomes relatively lower because people become taller as they grow.

Compared to the group with a lower BMI and visceral fat area, the relative risk of obesity-related diseases in higher BMI and visceral fat area group was 2.18 to 10.15, showing lower relative risk than that in the study on adults.9 The relative risk increased with a bigger visceral fat area, rather than with a higher BMI. This result suggests that obesity-related diseases occur less in younger age even if a similar degree of abdominal obesity exists, and that the visceral fat area is more important than the BMI in the evaluation of the risk of obesity-related diseases in children and adolescents.

This study had a few limitations. The result of this study cannot be generalized in all children and adolescents or in subjects with normal weight, as this study was conducted on obese children and adolescents who visited university hospitals. Furthermore, the hormone effect was not evaluated, as the menarche was not checked in girls. Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study is valuable in that it suggested the cut-off values of the visceral fat area and the waist-to-height ratio that predict the risk of obesity-related diseases rather than the cut-off values that simply diagnose an overweight condition and obesity, and provided a foundation for implementation in clinical practice.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curve of cut-off value of visceral fat area (VFA) to increase the obesity-related disorder. (A) Age 10-15. (B) Age 16-18.

Fig. 2

Correlations between visceral fat area (VFA) and waist-to-height ratio. In age 10-15, the vertical and horizontal lines represent VFA of 68.57 cm2 and the waist-to-height ratio corresponding to a VFA of 68.57 cm2 by simple regression line. In age 16-18, the vertical and horizontal lines represent VFA of 71.10 cm2 and the waist-to-height ratio corresponding to a VFA of 71.10 cm2 by simple regression line.

References

1. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002. 288:1723–1727.

3. Daniels SR, Morrison JA, Sprecher DL, Khoury P, Kimball TR. Association of body fat distribution and cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents. Circulation. 1999. 99:541–545.

4. Dalton M, Cameron AJ, Zimmet PZ, Shaw JE, Jolley D, Dunstan DW, et al. Waist circumference, waist-hip ratio and body mass index and their correlation with cardiovascular disease risk factors in Australian adults. J Intern Med. 2003. 254:555–563.

5. Pouliot MC, Després JP, Lemieux S, Moorjani S, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol. 1994. 73:460–468.

6. Després JP, Nadeau A, Tremblay A, Ferland M, Moorjani S, Lupien PJ, et al. Role of deep abdominal fat in the association between regional adipose tissue distribution and glucose tolerance in obese women. Diabetes. 1989. 38:304–309.

7. Seidell JC, Oosterlee A, Deurenberg P, Hautvast JG, Ruijs JH. Abdominal fat depots measured with computed tomography: effects of degree of obesity, sex, and age. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1988. 42:805–815.

8. Examination Committee of Criteria for 'Obesity Disease' in Japan. Japan Society for the Study of Obesity. New criteria for 'obesity disease' in Japan. Circ J. 2002. 66:987–992.

9. Kim JA, Choi CJ, Yum KS. Cut-off values of visceral fat area and waist circumference: diagnostic criteria for abdominal obesity in a Korean population. J Korean Med Sci. 2006. 21:1048–1053.

10. Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome--a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005. 366:1059–1062.

11. Savva SC, Tornaritis M, Savva ME, Kourides Y, Panagi A, Silikiotou N, et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio are better predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in children than body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000. 24:1453–1458.

12. Weili Y, He B, Yao H, Dai J, Cui J, Ge D, et al. Waist-to-height ratio is an accurate and easier index for evaluating obesity in children and adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007. 15:748–752.

13. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005. 112:2735–2752.

14. Kim JA, Park HS. Association of abdominal fat distribution and cardiometabolic risk factors among obese Korean adolescents. Diabetes Metab. 2008. 34:126–130.

15. Reinehr T, Wunsch R. Relationships between cardiovascular risk profile, ultrasonographic measurement of intra-abdominal adipose tissue, and waist circumference in obese children. Clin Nutr. 2010. 29:24–30.

16. Hsieh SD, Yoshinaga H, Muto T. Waist-to-height ratio, a simple and practical index for assessing central fat distribution and metabolic risk in Japanese men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003. 27:610–616.

17. McCarthy HD, Cole TJ, Fry T, Jebb SA, Prentice AM. Body fat reference curves for children. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006. 30:598–602.

18. Guntsche Z, Guntsche EM, Saraví FD, Gonzalez LM, Lopez Avellaneda C, Ayub E, et al. Umbilical waist-to-height ratio and trunk fat mass index (DXA) as markers of central adiposity and insulin resistance in Argentinean children with a family history of metabolic syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2010. 23:245–256.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download