Abstract

Purpose

The lateralization of cognitive functions in crossed aphasia in dextrals (CAD) has been explored and compared mainly with cases of aphasia with left hemisphere damage. However, comparing the neuropsychological aspects of CAD and aphasia after right brain damage in left-handers (ARL) could potentially provide more insights into the effect of a shift in the laterality of handedness or language on other cognitive organization. Thus, this case study compared two cases of CAD and one case of ARL.

Materials and Methods

The following neuropsychological measures were obtained from three aphasic patients with right brain damage (two cases of CAD and one case of ARL); language, oral and limb praxis, and nonverbal cognitive functions (visuospatial neglect and visuospatial construction).

Crossed aphasia in dextrals (CAD) is defined as aphasia in a right-handed person due to right cerebral lesion only. The estimated incidence of CAD has been reported to be less than 3% of all aphasic cases according to the literatures.1-8 More than two hundreds of CAD cases have been reported since the first clinical observation of CAD by Bramwell,9 and the criteria for CAD diagnosis have been modified since then.8 Recent case studies employed the following criteria: 1) evidence of aphasia, 2) clear lesion of vascular origin in the right hemisphere, 3) strong right-handedness with no left-handedness in the family, 4) absence of early brain damage, and 5) absence of environmental factors suspected to influence hemispheric dominance for language, such as tonal and ideographic languages, bilingualism, or illiteracy.2,6,7,10 A variety of theories suggesting causative factors of CAD have been proposed, including the right shift theory of Annett,11 where the presence of a single gene (rs+) is proposed to control natural variations in brain organization. However, a universally accepted theory does not still exist.

The studies of CAD have mainly been focused on the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the functional neurocognitive lateralization and organization of the brain,8 and concerns dissociation among neuropsychological symptoms that accompany language deficits in CAD, such as a dissociation between language and handedness, language and praxis, or other cognitive functions. Such functional dissociations suggest that CAD may be the source of more detailed information about the functional organization of the cognitive system.2

Aphasia after right brain damage in left-handers (ARL) is relatively common, therefore, it has received less attention than CAD.12 However, the clinical typology of ARL may not be identical to that of typical aphasia. Alexander and Annett13 mentioned that ARL shows the lateralization of some cognitive functions similar to CAD, comparing the neuropsychological aspects of CAD and ARL could provide more insights into the effect of a shift in the laterality of handedness or language on other cognitive organization.

Therefore, we investigated the neuropsychological aspects of two cases of CAD and one case of ARL: language, handedness, oral and limb praxis, and nonverbal cognitive functions including hemispatial neglect and visuospatial constructive ability. The comparisons of neuropsychological measures in three aphasic patients after right brain damage were expected to provide more information on dissociations among neuropsychological symptoms and the variability of the functional organization of cognitive system.

All three patients were aphasics after right brain damage: two (case 1 and 2) were right-handed and case 3 was left-handed. The two right-handed patients met the criteria for CAD.2,6,7,10 The left-handed patient also had no previous developmental and neurological disorders, prior stroke, or environmental factors that could have influenced hemispheric dominance for language. After suffering a stroke in the right hemisphere, all of the patients were diagnosed with global aphasia at the initial language evaluation and improved to Broca's aphasia at the second evaluation. The detailed histories of the three patients are described below.

She was a 45-year-old unmarried woman with 12 years of formal education. She was fully right-handed with a laterality quotient (LQ) of +100 when formally assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory,14 and according to her sister, all members of her immediate family are right-handed. In June 2006, her sister found her unconscious in the yard, and she was brought to an emergency room. Computed tomography of the brain performed immediately after admission revealed a massive intracerebral hemorrhage on the right basal ganglia associated with a small subarachnoid hemorrhage on the right sylvian cistern (Fig. 1). Due to hemorrhage midline shifting to left side of brain and compression of right inferior frontal gyrus, homologue to Broca's area, wereobserved.

At her first visit to the speech and language therapy room (2 months post-onset), she tried to speak, but any attempt to speak resulted in mere grunting or phonating. Thus, the scores of spontaneous speech, repetition and naming were scored as zero. She could perform some automatic speech tasks, such as counting or singing. Her auditory comprehension was also poor, with a score of 1.7 out of a total of 10. She could answer correctly to some yes/no questions and respond adequately by pointing out a real object in the task of auditory word recognition. She was diagnosed with severe global aphasia with aphasia quotient (AQ) of 3.4 by the Korean version of the Western Aphasia Battery (K-WAB).15

Case 2 was a 68-year-old right-handed man with an LQ of +100, and had 12 years of formal education and managed a noodle restaurant. According to his wife, there was no history of left-handedness in his family. In July 2006, he suffered from an ischemic stroke in the right hemisphere. He was transferred to our department after spending 5 months in the intensive care unit of another hospital. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain performed 5 months post-onset showed a large infarction in the superior division of right middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory (Fig. 2). The infarcted areas included right inferior frontal gyrus, insula, and primary motor cortex of oromotor function representing homologue to left anterior perisylvian language areas. Also right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, premotor and primary motor cortex for upper limb were involved.

At the initial language evaluation (5 months post-onset), he was diagnosed with global aphasia with an AQ of 38.6 determined by the K-WAB. His fluency (3.5/10) and naming (5.7/10) were relatively good, but his auditory comprehension was poor (1.9/10). His articulation was intact in spite of the salient agrammatic verbal production, showing total omission of postpositional words. Another speech characteristic of this patient was two or three repetitions of whole word or whole phrase; for example, he answered "family seven, family seven, a daughter, a daughter, a daughter" to a question about his family.

He was a 46-year-old married man with 9 years of formal education. Prior to his stroke, he had been working for many years as an ice cream wholesaler and was a skilled mountaineer. He was a moderate left-hander with an LQ of -60. On January 17, 2007, his wife found him unable to speak, exhibiting left-sided weakness. He was immediately brought to an emergency room. Brain MRI performed one week after admission showed a right MCA territorial infarction in the frontotemporal and temporoparietal lobes (Fig. 3). The areas of infarction included right temporal lobe, inferior parietal lobule, inferior frontal gyrus and insula cortex. Infarction of right posterior limb of internal capsule was also noted.

At the initial language evaluation (2-weeks post-onset), he was diagnosed with severe global aphasia with an AQ of 6.2, determined by the K-WAB. He was able to respond to the examiner's questions only by pointing a finger, nodding his head or by saying a combination of nonsense syllables. Both his fluency (0.5/10) and auditory comprehension (2.6/10) were very poor, and he could not score any points on the naming and repetition tasks.

We evaluated language, praxis and cognitive functions in 3 cases. Language ability was re-examined by the K-WAB within a week after the patients were subjected to a neuropsychological evaluation. In order to avoid remote functional effects of the hemorrhagic lesion, generally accounting for the instability of aphasic profiles during the first two or three weeks post-onset (acute phase), extensive language and neuropsychological examinations were performed at least six weeks after the onset.

To assess oral and verbal praxis as well as limb praxis, we used the informal, Korean-version of apraxia battery, which was modified from the Apraxia Battery for Adults.16 Before the evaluation of non-verbal cognitive functions, patients underwent the Korean version of Mini Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) as a general measure of cognitive screening.17 The Star Cancellation Test18 and Bells Test19 were used to evaluate visuospatial neglect. The drawing and the block design of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale20 were used to evaluate two- or three-dimensional constructive abilities. The copy and immediate recall subtests of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (ROCF)21 were used as another measurement of visuospatial constructive ability. The other subtest of ROCF, the delayed recall, was not carried out because of its complex domain associated with the memory, which was not within our focus. Finally, we evaluated the non-verbal intelligence by Raven's Coloured Progressive Matrices (RCPM).22

Informed consent to the procedures was obtained from all participants, and the Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee and the Committee on Experimental Procedures Involving Human Subjects of the Korea University Medical Center approved this study.

All three patients scored very low on the K-MMSE, which may have been largely attributable to their impaired language abilities. MMSE score was the lowest (0/30) in case 3, and 3/30 in case 1, and 10/30 in case 2, which was the same as the order of K-WAB scores.

At the second language evaluation (10 months post-onset), case 1 could say brief phrases, such as "hello" or "good-bye", answer "yes", and name certain objects when provided with the cue of the first syllable of the name. Auditory comprehension was improved so much that she correctly performed some tasks of sequential commands, and she scored 6 out of 10 on a test of auditory comprehension. However, she continued to have difficulty with repetition and naming, with scores of 1.6 and 1.2, respectively. At the second language evaluation, she was diagnosed with Broca's aphasia with an AQ of 25.6.

One month after the first language evaluation, language skills of case 2 improved with an AQ of 46.6, and he was diagnosed with Broca's aphasia. His auditory comprehension improved (4.2/10), but his speech characteristics, including agrammatism and repetition of words or phrases, were preserved.

The second K-WAB was performed to case 3 one month after his first evaluation of language performance. Language skills of case 3 had slightly improved to an AQ of 10.2, and he was classified as having Broca's aphasia because his auditory comprehension score was greater than 4 out of 10. His spontaneous speech score did not change because there was no word that he could intentionally pronounce, except for a few involuntary simple words, such as "hello", "don't know", or "here". Any attempt to speak voluntarily resulted in mere neologism or nonsense syllables.

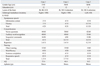

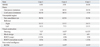

Table 1 displays a summary of the patients' demographic data, etiologies, handedness, and neurolinguistic findings.

In the neuropsychological tests performed at approximately the same time as the second language evaluation, case 1 displayed severe verbal and oral apraxia but normal limb praxis. Regarding her verbal praxis ability, she was able to repeat only two of one syllable-repetition tasks, and one of two syllable-repetition tasks, however, she could not repeat any of three syllable-repetition tasks out of ten stimuli respectively, in the task of increasing word length. The diadochokinetic rate could not be determined due to her poor performance on fast repetition tasks, even in the alternating motion task (the same syllable repetition task). Neither latency and utterance time nor repeated trials test scores could be examined. In the test of oral and limb apraxia, she was instructed to imitate the movements performed by the examiner in case of the failure to produce correct movements in response to a verbal command. She showed no difficulty with limb gestures (10/10), but she could imitate only one time in the tasks of oral imitation (1/10).

Case 2 had no oral or limb apraxia. His diadochokinetic rate was within normal range, and he had no difficulty performing any tasks designed to examine verbal praxis skills. In the test of oral and limb apraxia, because of his total failure to produce correct movements in response to a verbal command, which must have been due to his poor auditory comprehension ability, he was instructed to imitate the movements performed by the examiner and he walked through all of the examiner's imitations.

Verbal praxis ability of case 3 could not be examined due to his poor verbal output, but he had no difficulty imitating oral movements. In the test of limb apraxia, he was able to produce or imitate 5 of the examiner's 10 limb gestures. Thus, he was regarded as displaying normal oral praxis but limb apraxia.

Regarding the details of the visuospatial neglect test, case 1 cancelled 38 of 54 stars, and all cancellation on the Star Cancellation Test was completely biased toward the right side. In the Bells Test, she correctly circled 11 of 15 bells on the right but nothing on the left side of the visual field. Construction ability in case 1 revealed an impaired ability to draw (7/27) and severely impaired block construction ability (0/9). Her ROCF copy score was also very poor (2.5/36). ROCF drawing of case 1 consisted of scattered and fragmented pieces, which were disorganized with the loss of spatial relations, just like those drawn by patients with right hemisphere lesions (Fig. 4).23

Constructive praxis of case 2 also revealed impaired ability to draw (10/30), characterized by many additional lines (Fig. 5), and a severely impaired block design ability (0/9). Left visuospatial neglect was observed, but it was less severe than that observed in case 1. He cancelled 43 of 54 stars in the Star Cancellation Test, and circled 7 of 15 bells on the left side and all bells in the right side in the Bells Test. His ROCF copy (Fig. 6) score was also very poor (4/36). He committed overall rotational and angular errors, which have been reported to be typical of patients with right hemisphere damage.24

Case 3 revealed impaired construction ability to draw (8.5/30) and block design (6/9), but it was better than that of the two other patients. He had no left visuospatial neglect. He cancelled 53 of 54 stars in the Star Cancellation Test, and he missed two bells on the left side and just one bell on the right side in the Bells Test. His ROCF copy (Fig. 7) score was poor (5/36); the picture was not well organized, and there were some distortions in the angular orientation of some parts, as observed in the drawing of case 2. However, spatial relations seemed to be preserved and coherent, although simplified in comparison with those of the two other patients. His visuospatial ability was found to be better on almost all tasks, compared to that of case 1 and 2.

Their immediate recall scores of ROCF were worse than their copy scores and they hardly gained any points. Out of total 36 points, case 1, 2 and 3 got 0, 1, and 1.5 points, respectively.

The RCPM was used to measure conceptualization of spatial design, which is regarded as a representation of nonverbal intelligence. This test revealed that the patients' nonverbal intelligence was also impaired. Both case 1 and 2 scored 10 out of 37 on the RCPM, and case 3 scored slightly better (15 out of 37).

Table 2 displays a summary of the results of neuropsychological tests in three cases.

The leading role of the left hemisphere in language and praxis control is well established. Similarly, there is general consensus that visuospatial abilities rely heavily upon the right hemisphere in people with conventional dominance.25

Castro-Caldas, et al.26 have proposed the existence of "clusters" of functions, which could be located in either the left or the right hemisphere, depending on the individual's genetic predisposition. They suggested that some basic physiological or psychological processes as well as functions may presumably be divided into three clusters as follows: 1) handedness and limb praxis; 2) language and oral praxis; and 3) those mechanisms whose disorders result in visual neglect and other visual perceptive disorders. Several reported cases, however, challenged this hypothes.25,27,28 In our study, only case 1 met all three cluster definitions. She was right-handed and had right brain damage, normal limb praxis, aphasia with oral apraxia, and impaired visuospatial functions, including left visual neglect. Case 2 met the first and third cluster definitions. However, he did not meet the second cluster definition, since he had aphasia without oral apraxia. This example supports the notion that language and oral praxis can shift hemispheres separately,8,13 and this was found in case 3 who also had normal oral praxis. Because his temporal lobe damage was more severe than that in the frontal lobe (Fig. 3), there is another possibility that he has preserved regions related to oral praxis in the right hemisphere. Moreover, case 3 showed no visuospatial neglect despite having other visuospatially-related cognitive deficits, and seemed to violate the third rule, even though such an occurrence has been reported to be significantly rare.13

In our three cases, the unchallenged rule is that of the first cluster: handedness and limb praxis. The two right-handed patients had normal limb praxis, and the left-handed patient had limb apraxia. This supports the notion that limb apraxia is associated with left hemisphere lesions in right-handed individuals, but being left-handed seems to imply that the right brain should have a substantial role controlling learned limb movements.13

The relationship between limb praxis and language or limb praxis and handedness is still a controversial issue. Some authors have written about a dissociation of language and limb praxis, exemplified in the presence of crossed aphasia with intact limb praxis,29,30 and conversely, crossed limb apraxia with intact linguistic functions.27 By contrast, however, there is an evidence to show crossed aphasia with limb apraxia.2 In their review article, Castro-Caldas, Confraria, & Poppe (1987) suggested that it is more appropriate for limb praxis to be treated in connection with handedness rather than with language.26

However, the findings of the recent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study, of Vingerhoets, et al.31 performed with normal subjects, supported the notion that handedness and limb praxis are not related, because two groups of opposite handedness showed only a marginal difference in cerebral activation during limb praxis tests. Nevertheless, the authors mentioned that language dominance was not assessed in their study, therefore, the possibility that an imbalance in language lateralization between the two groups might affect their results could not be ruled out.31 Thus, the relationship between language, handedness, and praxis seems to be so complex that they should be considered all together.

Aphasia is generally accompanied by signs of non-verbal dysfunction.26 Possible interactions between non-verbal functions and language ability in aphasic patients have attracted the interest of researchers. Some investigators have reported the relationship between non-verbal functions and aphasia severity,32-34 while other investigators described a significant correlation between the AQ and scores on constructional and visuospatial tasks.15,35

In CAD, typical non-dominant hemisphere symptoms such as left visuospatial neglect and visuoconstructional apraxia have frequently been reported.8 In 82% of 66 reviewed CAD cases, Castro-Caldas, et al.26 found left visuospatial neglect, twice the incidence of 33-46% reported in cases with right hemisphere lesions and left hemisphere language dominance and in 76% of the cases, they found constructional apraxia, which is significantly higher than 45% reported for uncrossed aphasia. In our two CAD cases, both language and visuospatial cognitive functions seemed to be mediated by the right hemisphere, consistent with the results of Castro-Caldas, et al.26

Case 3, who is ARL, scored higher on the Block Design, RCPM and ROCF-copy than the other two patients; however, his scores on the K-WAB and K-MMSE were the lowest of the three. Given that all tasks were performed using his non-preferred, right hand, his abilities might have been underestimated, and his actual visuospatial ability might be better than the scores suggest. Moreover, he had no visuospatial neglect. If an AQ and visuospatial, constructional ability is highly correlated,15,35 then the test results of case 3 indicate that nonverbal cognition does not have to lateralize entirely to one hemisphere. Better visual cognitive functioning, as compared to the lower AQ, may suggest that some of this ability is located in the left hemisphere, which appeared to be intact. Furthermore, this result suggests the possibility of bilaterality of visual cognitive functions.

However, case 3 underwent language and neuropsychological examinations in the lesion phase, whereas the other two patients were examined in the late phase. Although the purest and most robust anatomo-clinical correlations are found during the lesion phase (from four weeks to four months post-onset), the various effects of recovery and functional brain reorganization could be captured in the late phase.36,37 Therefore, future studies to clarify these issues by means of follow-up examinations are recommended.

A close look at the ROCF scores of the three patients provides valuable information about their constructional abilities. The performances of case 1 and 2, both of whom had crossed aphasia, have some characteristics similar to those of right hemisphere stroke patients, including scatteredness and fragmentation (case 1), and faulty orientation and addition of lines (case 2). On the other hand, case 3 showed some similarity to that of patients with left hemisphere strokes, including preservation of spatial relations and coherency. If case 3 had the pattern of constructional ability, classically dominated by the left hemisphere, the functions of each hemisphere could be crossed over, which is another possible explanation for the lateralization of cognitive functions in case 3. In other words, language and constructional ability in the left hemisphere could be located in the right hemisphere, and the mechanism whose disorder results in visual neglect and constructional ability in the right hemisphere may be located in the left hemisphere. However, we are not certain whether a shift in the laterality of handedness influences the lateralization of some cognitive functions or whether a shift in the laterality of handedness is the result of reversal of cognitive functions.

The frequency of constructional apraxia still appears quite variable. This discrepancy is likely due to the variability in the definition of constructional apraxia.6 Kleist38 defined constructional apraxia as an impaired ability to purposefully and accurately shape or assemble materials, or draw pictures, despite the absence of apraxia in isolated movements and certain aspects of performance. This definition distinguishes constructional apraxia from limb apraxia. On the other hand, some authors included neglect or visuospatial difficulties as a part of constructional apraxia without additional explanations on limb apraxia.6 In our study, the patients with CAD (case 1 and 2), seemed to show signs of constructional apraxia, including impairment of visual perception, whereas the patient with ARL (case 3) seemed to show signs of constructional apraxia, including limb apraxia. Constructional apraxia cannot be considered as a unitary syndrome.39 Thus, qualitative analysis of constructional representations could provide more information on the characteristics of patients' visuospatial cognition.

In conclusion, insummary, two right-handed patients (case 1 and 2) had normal limb praxis, and one left-handed patient (case 3) had limb apraxia, in support of the notion that a shift in the laterality of handedness influences the lateralization of limb praxis. Furthermore, the normal oral praxis in case 2 and 3 suggests that their language and oral praxis may lateralize independently of each other or that they may have preserved regions related to oral praxis in the right hemisphere. In two cases with CAD, both language and visuospatial cognitive functions seem to be mediated by the right hemisphere, while in a case of ARL the possibility of bilateral or some crossed-over visuospatial cognitive functions may be suggested.

Cognitive difficulties could often be overshadowed or obscured by language impairment and vice versa. Detailed analysis of cases may contribute to the understanding of the mechanisms of lateralization and representation of language and cognitive functions in the damaged human brain.

However, this study draws on limited samples and, consequently, its results are not generalizable, indicating that there is a need for future studies to adduce more samples.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Brain CT of case 1 indicating a massive intracerebral hemorrhage on the right basal ganglia. CT, computed tomography. |

| Fig. 2Brain MRI of case 2 indicating infarction of right middle cerebral artery (superior division). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. |

| Fig. 3Brain MRI of case 3 indicating total infarction of right middle cerebral artery. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2009-32A-H00017).

References

1. Alexander MP. Feinberg TE, Farah MJ, editors. APhasia: Clinical and anatomic issues. Behavioral neurology and neuropsychology. 2003. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;147–164.

2. Bartha L, Mariën P, Poewe W, Benke T. Linguistic and neuropsychological deficits in crossed conduction aphasia. Report of three cases. Brain Lang. 2004. 88:83–95.

3. Borod JC, Carper M, Naeser M, Goodglass H. Left-handed and right-handed aphasics with left hemisphere lesions compared on nonverbal performance measures. Cortex. 1985. 21:81–90.

4. Brown JW, Hécaen H. Lateralization and language representation. Neurology. 1976. 26:183–189.

6. Coppens P, Hungerford S, Yamaguchi S, Yamadori A. Crossed aphasia: an analysis of the symptoms, their frequency, and a comparison with left-hemisphere aphasia symptomatology. Brain Lang. 2002. 83:425–463.

7. Lessa Mansur L, Radanovic M, Santos Penha S, Iracema Zanotto de Mendonça L, Cristina Adda C. Language and visuospatial impairment in a case of crossed aphasia. Laterality. 2006. 11:525–539.

8. Mariën P, Engelborghs S, Vignolo LA, De Deyn PP. The many faces of crossed aphasia in dextrals: report of nine cases and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2001. 8:643–658.

9. Bramwell B. On "crossed" aphasia. Lancet. 1899. 1:1473–1479.

11. Annett M. A single gene explanation of right and left handedness and brainedness. 1978. Coventry, UK: Lanchester Polytechnic.

12. Joanette Y. Boller F, Grafman J, editors. Aphasia in left-handers and crossed aphasia. Handbook of neuropsychology. 1989. Amsterdam: Elsevier;173–183.

13. Alexander MP, Annett M. Crossed aphasia and related anomalies of cerebral organization: case reports and a genetic hypothesis. Brain Lang. 1996. 55:213–239.

14. Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971. 9:97–113.

15. Kim HH, Na DL. Korean-version Western Aphasia Battery (K-WAB). 2001. Seoul: Paradise Welfare Foundation.

16. Dabul BL. Apraxia battery for adults: Examiner's manual and picture plates. 1979. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

17. Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1997. 15:300–308.

18. Wilson B, Cockburn J, Halligan P. Development of a behavioral test of visuospatial neglect. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987. 68:98–102.

19. Gauthier L, Dehaut F, Joanette Y. The Bells Test: a quantitative and qualitative test for visual neglect. Int J Clin Neuropsychol. 1989. 11:49–54.

20. Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler adult intelligence scale. 1995. New York: Psychological Corporation.

21. Visser RSH. Manual of the complex figure test CFT. 1973. Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger.

22. Raven JC. Guide to the standard progressive matrices: sets A, B, C, D and E. 1960. London: H.K. Lewis.

23. Piercy M, Hecaen H, de Ajuriaguerra . Constructional apraxia associated with unilateral cerebral lesions-left and right sided cases compared. Brain. 1960. 83:225–242.

24. Laeng B. Constructional apraxia after left or right unilateral stroke. Neuropsychologia. 2006. 44:1595–1606.

25. Marchetti C, Carey D, Della Sala S. Crossed right hemisphere syndrome following left thalamic stroke. J Neurol. 2005. 252:403–411.

26. Castro-Caldas A, Confraria A, Poppe P. Non-verbal disturbances in crossed aphasia. Aphasiology. 1987. 1:403–413.

27. Marchetti C, Della Sala S. On crossed apraxia. Description of a right-handed apraxic patient with right supplementary motor area damage. Cortex. 1997. 33:341–354.

28. Raymer AM, Merians AS, Adair JC, Schwartz RL, Williamson DJ, Rothi LJ, et al. Crossed apraxia: implications for handedness. Cortex. 1999. 35:183–199.

30. Mendez MF, Benson DF. Atypical conduction aphasia. A disconnection syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1985. 42:886–891.

31. Vingerhoets G, Acke F, Alderweireldt AS, Nys J, Vandemaele P, Achten E. Cerebral lateralization of praxis in right- and left-handedness: same pattern, different strength. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012. 2011. [Epub ahead of print].

32. Basso A, De Renzi E, Faglioni P, Scotti G, Spinnler H. Neuropsychological evidence for the existence of cerebral areas critical to the performance of intelligence tasks. Brain. 1973. 96:715–728.

33. Kertesz A, McCabe P. Intelligence and aphasia: performance of aphasics on Raven's coloured progressive matrices (RCPM). Brain Lang. 1975. 2:387–395.

34. Maeshima S, Ueyoshi A, Matsumoto T, Boh-Oka S, Yoshida M, Itakura T. Quantitative assessment of impairment in constructional ability by cube copying in patients with aphasia. Brain Inj. 2002. 16:161–167.

35. Pyun SB, Yi HY, Hwang YM, Ha J, Yoo SD. Is visuospatial cognitive function preserved in aphasia? J Neurol Sci. 2009. 283:304.

36. Mazzocchi F, Vignolo LA. Localisation of lesions in aphasia: clinical-CT scan correlations in stroke patients. Cortex. 1979. 15:627–653.

37. Alexander MP. Boller F, Grafman J, editors. Clinical-anatomical correlations of aphasia following predominantly subcortical lesions. Handbook of neuropsychology. 1989. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science;46–66.

38. Kleist K. Gehirnpathologie. 1934. Leipzig: Barth.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download