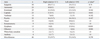

The frequency of auras in our study subjects was 64%. This percentage is lower than 81% that was reported in Palmini and Gloor's

2 study of 179 subjects with mixed lobar epilepsies, who underwent prolonged EEG monitoring or surgical treatment. However, our percentage is identical to 64% that was reported in a study that had investigated the relationship between auras and the lateralization of the EEG abnormalities for 290 subjects with TLE on an outpatient basis, which is a population that could be expected to have a higher frequency of auras.

13 The mean number of auras and the proportion of subjects with at least one aura were significantly lower in subjects with FLE, and this finding was consistent with a previously published study.

2

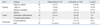

Localizing value of auras

In the present study, the association between epigastric auras and MTLE is consistent with the previously published findings.

2,

13,

14 Epigastric auras are occasionally observed in subjects with extratemporal epilepsy, particularly FLE subjects,

15 and can be reproduced by the stimulation of the extratemporal lobe, as well as the temporal lobe.

16 This is in agreement with our findings that epigastric auras were also observed in three FLE subjects, but not in any of the PLE or OLE subjects.

Autonomic symptoms, such as sweating, sialorrhea, palpitation, and respiratory difficulty, were included as symptoms of autonomic auras, while we categorized nauseous feelings as a symptom of epigastric auras. However, epigastric and autonomic auras were classified as only one category of viscerosensory aura in previous studies.

1,

2 In this study, autonomic auras also showed a pattern of distribution similar to epigastric auras. However, the autonomic auras were more frequently reported by subjects with MTLE than those with LTLE.

Psychic auras correspond to the experiential auras discussed in Palmini and Gloor's study,

2 except that, the complex visual and auditory hallucinations were categorized as visual and auditory auras, respectively in our study. Psychic auras auras were frequently reported by subjects with TLE. Similar to the results of Palmini and Gloor's study, in which three patients with occipital and two patients with frontal lobe seizure focus showed experiential auras,

2 two subjects with FLE and one subject with OLE in our study also had psychic auras. Considering the fact that psychic symptoms were reproduced by electrical stimulation of the temporal lobe,

2,

17-

21 we speculate that psychic auras in the subjects with OLE and FLE may result from the spread of seizure discharge to the temporal lobe structures.

When the psychic auras were subdivided into memory-related type and memory-unrelated type, only the memory-related type had a tendency to be more common in MTLE subjects. This may be due to the memory-related structures, such as the hippocampus or the amygdala, which are located in the mesial temporal lobe.

The association of visual auras with PLE and OLE is consistent with what has been previously reported.

2 In the present study, complex visual hallucinations were regarded as visual auras that were then subdivided into three subcategories; visual illusions, elementary visual hallucinations, and complex visual hallucinations. Among the three subtypes of visual auras that were studied, visual illusions and elementary visual hallucinations were associated more with PLE and OLE. Our finding that complex visual hallucinations were observed in LTLE and PLE subjects, but not in OLE subjects is in agreement with the findings of a previous study on visual auras.

9 Although elementary visual hallucinations were not reported in FLE in previous studies,

2,

22 two subjects with FLE in this study had their lesions near the parietal lobe and had reported nonspecific features of elementary visual hallucinations, such as darkening and orange sunshine in their entire visual field.

In the present study, emotional auras were observed in all of the categories of lobar epilepsy. The two patients in our study who reported euphoria as their auras had left-sided LTLE. This localizing and lateralizing value requires further investigation with more patients in order to confirm this finding.

All six subjects with olfactory auras in this study had TLE. Among these subjects, two had atrophic lesions in the temporal pole area. The other four subjects had lesions in the mesial temporal region, which commonly involved the amygdala and the types of lesions were a benign tumor, HS, cortical dysplasia, and an atrophic lesion. Olfactory auras were produced by the stimulation of the mesial temporal structures, which include the uncus and the amygdala or the olfactory bulb,

19 and are associated with MTLE and mesial temporal pathology.

6,

10 In this study, the olfactory auras in the subjects with LTLE may be due to the spread of the seizure activity to the mesial temporal lobe structure or due to the involvement of the mesial temporal lobe structure related to head trauma, which cannot be resolved with a MRI.

Of the four subjects with auditory auras, three had lesions in the temporal lobe, and the other one subject had a lesion in the parietal lobe. The subject with PLE had a focal infarction in the left parietal lobe and an elementary auditory hallucination that presented itself as a buzzing sound. This finding is different from previous reports in that all subjects with auditory aura had TLE.

1,

2 Since this patient also experienced complex visual hallucinations and whole body sensations, the auditory aura may be due to the spread of seizure discharge from the parietal to the temporal lobe structure.

In the analysis of aura frequency between the subjects with specific lobar epilepsy and those without, whole body sensations and somatosensory auras were found to be more common in PLE subjects. This finding is consistent with previously published results that the somatosensory auras are associated with PLE patients.

2

Vestibular, cephalic, and dysphasic auras had no definite localizing value in this study. Cephalic auras, which have been reported to have a significant association with FLE in a previous study,

2 were diffusely distributed in all of the categories of lobar epilepsy. Penfield and Jasper

23 have reported that electrical stimulation in either the parietal or temporal regions were observed to produce a sensation of vertigo. In this study, however, the vestibular auras were reported in all lobar epilepsies, which is consistent with the findings of another previously published study.

2 Vertigo is thought to be caused by the mismatch between visuospatial and vestibular information,

24 which could explain the significant correlation between vestibular and visual auras in our study.

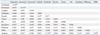

Lateralizing value of auras

Previous studies on the lateralizing value of auras failed to confirm their findings.

1,

2 Only in an EEG-clinical correlation study, Gupta, et al.

13 were able to observe that autonomic and psychic auras were more frequently associated with right-sided EEG abnormalities in TLE patients. In the present study, only the dysphasic auras were found to correlate with the side on which the lesion was present, verified by the brain MRI. The correlation of dysphasic auras with left-sided epilepsy seems to be plausible since the language centers are usually located in the left hemisphere of the brain. However, previous studies did not categorize this type of aura into its own aura categorization.

1,

2,

13 In our study, psychic auras and déjà vu illusions did not show any significant preference for lateralization. In Palmini and Gloor's

2 study, there was a strong trend of experiential auras and déjà vu illusions to originate from the right temporal lobe. Some stimulation studies showed that electrical stimulation of the right temporal lobe yielded more experiential responses and déjà vu illusions than that of the left lobe.

17,

18

In this study, vestibular auras tended to occur more frequently in subjects with right-sided epilepsy (seven out of ten subjects), although previous studies did not find lateralizing value of vestibular auras.

1,

2,

13 Considering the dominant right hemispheric influence on visuospatial information processing, our data reflect the possibility that the right hemisphere may play a significant role in the expression of the vestibular aura. Furthermore, our present study showed that the olfactory auras tended to be more common in right-sided epilepsy (

p=0.087), in which five of the six subjects with olfactory auras had right-sided epilepsies. However, there has been no significant preponderance for lateralization in previous studies.

2,

6,

10,

13

In this study, there was a significant correlation between autonomic auras and the emotional auras, particularly bad feeling in left-sided epilepsy patients. Lee, et al.

25 found that patients with left-sided TLE exhibited autonomic hyperarousal when viewing negative emotional slides relative to controls and those with right-sided TLE. They suggested that the dysfunction of the left mesial temporal lobe structures may result in autonomic hyperarousal and a release of the unrestrained negative emotional tendencies of the right hemisphere. Morrow, et al.

26 also reported less prominent autonomic arousal to emotionally loaded visual materials in persons with non-dominant hemisphere damage than in the control subjects or those with dominant hemisphere damage. Therefore, the association of autonomic auras and emotional auras in left-sided epilepsy patients might be explained in a similar context.

There are major limitations in this study. Patients with only lesional epilepsy were selected. Therefore, without intracranial EEG evaluations or surgical outcomes, the possibility of false localization of the epileptogenic zone by lesion exists, especially in patients with atrophic lesions that are related to infectious, traumatic, or unknown etiology. The exact nature of auras was not confirmed by video-EEG monitoring in most patients. Patients with an extratemporal lesion (epilepsy) who could show temporal IEDs were excluded in this study, which may reflect too small number of patients with OLE, thus preventing appropriate analysis of OLE. These limitations may make the present results difficult to apply to overall partial epilepsy. However, the analysis of auras in patients with a lesion highly suggestive of epileptogenic focus may provide some clinical value.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the previously known localizing value of auras in surgical epilepsy patients can be applied to patients with partial epilepsy on an outpatient basis. In addition, with a broader range of subjects, we were able to find the lateralizing values of dysphasic auras and the laterality-specific concurrent tendency of autonomic-emotional auras.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download