Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to determine whether 12 core-extended biopsies of the prostate could predict insignificant prostate cancer (IPCa) in Koreans reliably enough to recommend active surveillance.

Materials and Methods

Two hundred and ninety-seven patients who underwent radical prostatectomy after 12 core-extended prostate biopsies were retrospectively reviewed. 38 cases (12.8%) were shown to be IPCa.

Results

The average age was 65.2 years, serum PSA was 5.49 ng/dL, and the PSA density was 0.11. The Gleason scores (GS) were 6 (3+3) in 31, 5 (3+2) in 4, and 4 (2+2) in 3. After radical prostatectomy, higher GS was given in 16 (42.1%), whereas lower GS was given in 1 case (2.6%), as compared with the GS obtained from biopsy. 11 (28.9%) had GS of 7 (3+4) and 5 (13.2%) had GS of 7 (4+3). 6 in GS 7 (4+3) and 1 in GS 7 (3+4) showed prostate capsule invasion and 1 in GS 7 (4+3) had seminal vesicle invasion. Prostate capsule invasion was observed in 1 with GS 6 (3+3). The rate of inaccuracy of the contemporary Epstein criteria was 42.1%. Only PSA density was a reliable indicator of clinically IPCa (odds ratio=1.384, 95% CI, 1.103 to 2.091).

Recently, prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer has become common, and the prostate biopsy technique has evolved, increasingly detecting clinically insignificant prostate cancer.1,2 However, there is no precise guideline for managing clinically insignificant prostate cancer (IPCa) with an early diagnosis.

The Epstein criteria is the most frequently used set of definitions for determining whether prostate cancer is clinically insignificant, and this criteria are the basis for starting active surveillance.3,4 However, there are some reports that the reliability of the Epstein criteria can vary by race or regions. This implies that the significance of the Epstein criteria can be different between Western and Asian men.5 Some authors have reported that the Epstein criteria may be inaccurate in Asians with prostate cancer. They reported that there was higher negative predictive value when the Epstein criteria were applied to IPCa patients in Asia than in any other country.6,7 Our aim was to determine whether 12 core-extended biopsies of the prostate could reliably predict IPCa in men who were candidates for watchful waiting. Our aim was also to determine trends in the incidence of IPCa after prostate biopsies and pathology upgrade after radical prostatectomy.

Two hundred and ninety-seven patients who had undergone a radical prostatectomy after 12-core transrectal ultrasonography-guided prostatic biopsies between January 2004 and December 2009 at our institution were enrolled for a retrospective analysis. Before initiating this study, we obtained approval from the institutional review board. We reviewed the specimens from prostatic biopsies and radical prostatectomies that had been performed in 2004 through to 2005 (group 1), 2006 through to 2007 (group 2), and 2008 through to 2009 (group 3). According to the Epstein criteria, IPCa was defined as a PSA density of less than 0.15 ng/dL, a biopsy Gleason score ≤6, less than or equql to 2 positive cores in 6 core biopsies, and a single core percentage under 50%.4,8 We excluded patients who had undergone prostate biopsy at other institution, hormone therapy or radiation therapy before the radical prostatectomy. The radical prostatectomy was performed by a single surgeon (B.H.C.).

A kit from BK Medical, Denmark was used for prostatic biopsies (right 6 cores and left 6 cores). The 12-core biopsies were done in each patient by a urologist with 12 years of experience. According to the standard of previous biopsy protocol, sextant biopsy was performed from the apex, mid, and base of the right and left parasagittal planes of the prostate including an additional 3 cores from the peripheral zone positioned more laterally on each side.8 Biopsy was performed either under local anesthesia or general anesthesia and 12 cores were obtained regardless of prostate volume. In cases under anesthesia, patients required a 3-5 day administration of fluoroquinolone and midnight NPO from the day before biopsy was performed, usually followed by a 3-5 day course of antibiotic treatment. The standard length of the biopsy cores was 15 mm, and each core was embedded separately. They were divided in multiple containers, and designated as either right or left standard sextant or lateral peripheral zone biopsy cores.9

The pathologic grading was done according to the Gleason scoring system, and the pathologic review was performed by a single experienced urologic pathologist (S.W.H.). The prostatectomy specimens were fixed overnight (10% neutral buffered formaldehyde) and coated with India ink. Transverse whole mount step section specimens were obtained at 4 mm intervals on a plane. The presence and extent of cancer were outlined on the glass cover. The presence of tumor cells beyond the capsular margin was defined as extracapsular extension. The largest tumor nodule was mapped and categorized according to grade, location, volume, pathologic stage and margin status. The volume was calculated using a computer assisted image analysis system.10

Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-test to evaluate the demographic and clinical differences between IPCa and significant PCa groups. Multivariate analysis was performed to determine the independent prognostic factors for IPCa. A chi-square test was used to compare groups for categorical variables, and a p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

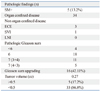

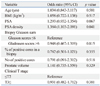

Of the 297 cases, 38 (12.8%) were found to be IPCa. The average age was 65.2 years, average serum PSA was 5.49 ng/dL, and average PSA density was 0.11. Table 1 shows the differences in preoperative clinical variables between the IPCa and significant PCa groups. The mean PSA and PSA density were 5.49 ng/mL and 0.11 in the IPCa group and 9.91 ng/mL and 0.42 in the significant PCa group (p=0.012, 0.027, respectively). After a radical prostatectomy, an upgraded Gleason score was found in 16 cases (42.1%) whereas a downgraded Gleason score occurred in 1 case (2.6%), when compared with the Gleason score from the biopsy (Table 2). Eleven cases (28.9%) of Gleason score 7 (3+4) and five cases (13.2%) of Gleason score 7 (4+3) were observed. Six cases of Gleason score 7 (3+4) and one case of Gleason score 7 (4+3) showed prostate capsule invasion and one case of Gleason score 7 (4+3) had seminal vesicle invasion. The inaccuracy of the contemporary Epstein criteria was 42.1%.

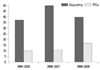

The incidence of IPCa after prostate biopsy showed a pattern of increase over time, especially in group 3. The proportion of IPCa was 8/81 cases (10.1%) in group 1, 10/94 cases in group 2 (10.6%), and 20/122 cases in group 3 (16.4%) (Fig. 1). However, there was no change of incidence with time to upgrade from IPCa to significant PCa after radical prostatectomy [3/8 cases (37.5%) in group 1, 5/10 cases (50%) in group 2, and 8/20 cases (40%) in group 3, respectively]. In the logistic regression analysis, only PSA density was found to be a predictable indicator for clinically IPCa (odds ratio=1.384, 95% CI, 1.103 to 2.091) (Table 3).

The contemporary Epstein criteria are the most widely used tool for predicting clinically IPCa.4,11 One study reported that the accuracy of the Epstein criteria in the USA was 84%, and that they underestimated the disease stage and/or grade in 16% of USA patients.4 Another study reported that 24% of male European patients who fulfilled the Epstein criteria for presence of clinically insignificant prostate cancer were incorrectly classified as having clinically IPCa.12 Gleason 7-10 prostate cancer at radical prostatectomy was found in 24% patients with clinically IPCa. The pathological characteristics of these 24% might actually represent an absolute contraindication to active surveillance or similar treatment modalities that are usually applicable for men with clinically IPCa. Lee, et al.6 reported an inaccuracy of the Epstein criteria of up to 30.5% in Korea. In our study, the inaccuracy of the Epstein criteria of our study was 42.1% and this is, to our knowledge, the highest reported value. This high inaccuracy rate of the Epstein criteria might be due to more aggressive and poorly differentiated prostate cancer in Korean men, despite a low clinical stage or low serum PSA level.13 Also, Man, et al.14 reported that a greater proportion of Asian patients present high risk prostate cancer than non Asian men. There were twice the percentage of Asian patients with Gleason scores 8 or greater than nonAsians at presentation. Prostate cancer of predominantly high grade in Korean men may be attributed to reduced testosterone metabolism. Hoffman, et al.15 illustrated that patients with a low serum-free testosterone level have an increased mean percentage of biopsies revealing cancer with a Gleason score of 8 or higher, suggesting that a low serum-free testosterone level may be a marker of more aggressive disease. In our current study, however, we are not certain whether there exists a relationship between aggressiveness of PCa and serum testosterone level. This hypothesis should be investigated in a future study.

In our study, PSA density was found to be a prognostic factor for clinically IPCa. The incidence of prostate cancer in the low PSA (2.5-4.0) group was reported to be more than 20% in Korea.16 Furthermore, PCa detected by biopsies with low PSA levels have been shown to be clinically significant, and there are no differences in pathologic stage and Gleason pattern between the preoperative low PSA and high PSA groups after radical prostatectomy.16-18 This implies that there are no definite preoperative variables for a diagnosis of clinically IPCa, thus confusing the diagnosis and treatment. Additional novel markers might be needed in order to elevate the predictive accuracy of the Epstein criteria.

Besides the high inaccuracy rate of the Epstein criteria in our study, the criteria showed no change of incidence of an upgrade from IPCa to significant one after radical prostatectomy. However, Chun, et al.19 found that the rate of upgrading decreased over time, from 52% to 27%, between 1992 and 2004. These contradictory results might result not only from different races, more aggressive tumor characteristics as compared to Western men,12 and environmental conditions, but also from the study design. Our study was carried out by a single surgeon and a single pathologist at a single institute, therefore, the quality of the data may be more homogenous than previous studies.

Because the incidence and mortality of PCa differ according to race and dietary habits, the accuracy of the Epstein criteria of studies in Asian countries is unlikely to be as accurate as other countries. This is very meaningful in determining the early stage treatment of PCa after a prostatic biopsy. Recently, there have been various treatment options developed for early prostate cancer, such as active surveillance, surgical treatment or radiation therapy.20 The optimal treatment of early PCa has been controversial; however, our present results indicate that caution should be advised when treatment decisions are based solely on the Epstein criteria, especially in Korea.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study with a relatively small number of patients enrolled, as it was conducted at a single institution. However, it should be noted that our cohort from a single surgeon may elevate the reliability of the results. Furthermore, considering the large difference in prostate cancer incidence between Korean and Western men, the number of men in the present series should not be considered too small for a single institution.6 Furthermore, as follow up was limited, we could not assess the biochemical recurrence or prognosis, which may be a more important issue than the presence of unfavorable pathological features.6 Further investigation is needed for the development of more accurate diagnostic tool of identifying Asian men with clinically IPCa.

The incidence of IPCa after prostate biopsy showed an increase with time. However, the Epstein criteria may not be validly applicable in Korean PCa patients because the inaccuracy rate of the criteria was as high as 42.1%. A modified diagnostic tool for active surveillance is necessary for Korean PCa patients.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Incidence of insignificant prostate cancer after prostate biopsy and upgraded pathology after radical prostatectomy. IPCa, insignificant prostate cancer.

References

1. Chun FK, Briganti A, Gallina A, Hutterer GC, Shariat SF, Antebie E, et al. Prostate-specific antigen improves the ability of clinical stage and biopsy Gleason sum to predict the pathologic stage at radical prostatectomy in the new millennium. Eur Urol. 2007. 52:1067–1074.

2. Yin M, Bastacky S, Chandran U, Becich MJ, Dhir R. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer in the general population: a study of healthy organ donors. J Urol. 2008. 179:892–895.

3. Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, Brendler CB. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA. 1994. 271:368–374.

4. Bastian PJ, Mangold LA, Epstein JI, Partin AW. Characteristics of insignificant clinical T1c prostate tumors. A contemporary analysis. Cancer. 2004. 101:2001–2005.

5. Chung JS, Choi HY, Song HR, Byun SS, Seo SI, Song C, et al. Nomogram to predict insignificant prostate cancer at radical prostatectomy in Korean men: a multi-center study. Yonsei Med J. 2011. 52:74–80.

6. Lee SE, Kim DS, Lee WK, Park HZ, Lee CJ, Doo SH, et al. Application of the Epstein criteria for prediction of clinically insignificant prostate cancer in Korean men. BJU Int. 2010. 105:1526–1530.

7. Hekal IA, El-Tabey NA, Nabeeh MA, El-Assmy A, Abd El-Hameed M, Nabeeh A, et al. Validation of Epstein criteria of insignificant prostate cancer in Middle East patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010. 42:667–671.

8. Chun FK, Briganti A, Jeldres C, Gallina A, Erbersdobler A, Schlomm T, et al. Tumour volume and high grade tumour volume are the best predictors of pathologic stage and biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Eur J Cancer. 2007. 43:536–543.

9. Gore JL, Shariat SF, Miles BJ, Kadmon D, Jiang N, Wheeler TM, et al. Optimal combinations of systematic sextant and laterally directed biopsies for the detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001. 165:1554–1559.

10. Partin AW, Epstein JI, Cho KR, Gittelsohn AM, Walsh PC. Morphometric measurement of tumor volume and per cent of gland involvement as predictors of pathological stage in clinical stage B prostate cancer. J Urol. 1989. 141:341–345.

11. Allan RW, Sanderson H, Epstein JI. Correlation of minute (0.5 MM or less) focus of prostate adenocarcinoma on needle biopsy with radical prostatectomy specimen: role of prostate specific antigen density. J Urol. 2003. 170(2 Pt 1):370–372.

12. Jeldres C, Suardi N, Walz J, Hutterer GC, Ahyai S, Lattouf JB, et al. Validation of the contemporary epstein criteria for insignificant prostate cancer in European men. Eur Urol. 2008. 54:1306–1313.

13. Song C, Ro JY, Lee MS, Hong SJ, Chung BH, Choi HY, et al. Prostate cancer in Korean men exhibits poor differentiation and is adversely related to prognosis after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2006. 68:820–824.

14. Man A, Pickles T, Chi KN. British Columbia Cancer Agency Prostate Cohort Outcomes Initiative. Asian race and impact on outcomes after radical radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003. 170:901–904.

15. Hoffman MA, DeWolf WC, Morgentaler A. Is low serum free testosterone a marker for high grade prostate cancer? J Urol. 2000. 163:824–827.

16. Kim HS, Jeon SS, Choi JD, Kim W, Han DH, Jeong BC, et al. Detection rates of nonpalpable prostate cancer in Korean men with prostate-specific antigen levels between 2.5 and 4.0 ng/mL. Urology. 2010. 76:919–922.

17. Sokoloff MH, Yang XJ, Fumo M, Mhoon D, Brendler CB. Characterizing prostatic adenocarcinomas in men with a serum prostate specific antigen level of < 4.0 ng/mL. BJU Int. 2004. 93:499–502.

18. Smith RP, Malkowicz SB, Whittington R, VanArsdalen K, Tochner Z, Wein AJ. Identification of clinically significant prostate cancer by prostate-specific antigen screening. Arch Intern Med. 2004. 164:1227–1230.

19. Chun FK, Steuber T, Erbersdobler A, Currlin E, Walz J, Schlomm T, et al. Development and internal validation of a nomogram predicting the probability of prostate cancer Gleason sum upgrading between biopsy and radical prostatectomy pathology. Eur Urol. 2006. 49:820–826.

20. Singh J, Trabulsi EJ, Gomella LG. Is there an optimal management for localized prostate cancer? Clin Interv Aging. 2010. 5:187–197.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download