Abstract

Purpose

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP) is rare among children. In most cases, XGP is diffusely or focally enlarged, mimicking the neoplastic process. The aim of this study was to examine clinical characteristics and outcomes of Korean children with XGP.

Materials and Methods

Fourteen children (9 boys, 5 girls) with XGP were reviewed retrospectively. The cohort included 2 children managed at our institution and 12 children reported in the Korean literature. The patients' records were reviewed with respect to age at diagnosis, clinical presentation, management method, and other characteristic features.

Results

The mean age was 79.4±66.5 months (range 1-168 months). Common clinical presentations included fever (85.7%), abdominal pain (57.1%), and palpable mass (28.6%). Laboratory abnormalities included leukocytosis (57.1%), anemia (57.1%), and pyuria (57.1%). The types of XGP that were diagnosed based on preoperative radiologic studies included the focal form in 9 children and the diffuse form in 5. Thirteen children underwent nephrectomy, and 1 child received conservative medical therapy.

Conclusion

The possibility of XGP should be considered if a child is diagnosed with a renal mass, especially if it is a small renal mass associated with fever, leukocytosis, or stone. Nephrectomy is the treatment of choice for the diffuse form, whereas partial nephrectomy or conservative medical therapy may be indicated to manage focal XGP.

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP) predominantly affects adults between 40 and 60 years of age who have a long-standing history of chronic pyelonephritis and urolithiasis.1 Each year, there are 1.4 cases per 100000 people worldwide.2 XGP is very rare among children. Only 265 cases have been reported in the English literature since 1960,3 and only 12 cases have been reported in the Korean literature since the first case reported by Ahn, et al. in 1977.4-10 Most cases were finally diagnosed by histopathology after nephrectomy, because the clinical and radiologic features are difficult to characterize. Differential diagnoses include Wilms' tumor, renal cell carcinoma, renal abscess, infected renal cystic disease, renal tuberculosis, malakoplakia, and transitional renal cell carcinoma.11 Therefore, it is important to establish the diagnosis before reaching a therapeutic decision, because a trial of antibiotic therapy or nephron sparing surgery is warranted, and unnecessary total nephrectomy may be avoided. The aim of the study was to examine the clinical characteristics and outcomes of this condition in Korean children.

We reviewed 14 XGP cases of children in the Korean literature. The electronic database KoreaMed, which covered the period between 1960 and 2009, was used. The search terms used were 'xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis', 'infant', 'child', 'childhood', and 'children'. We extracted 12 cases from the Korean Journal of Urology (7 cases), Korean Journal of Pediatrics (4 cases), and Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (1 case), and we added 2 more patients diagnosed at our institution. For each characteristic finding identified, a case review was performed to document the clinical symptoms, physical examinations, laboratory findings, imaging studies, preoperative diagnosis, histopathologic diagnosis, and management method. Statistically significant differences were determined using the Fisher's exact test or analysis of variance. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statically significant.

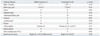

The mean age of 14 patients (9 boys and 5 girls) (10 right kidneys, 3 left kidneys, and 1 both kidneys) identified was 79.4±66.5 months (range 1-168 months). The common clinical presentations were as follows: fever (85.7%), abdominal pain (57.1%), palpable mass (28.6%), anorexia (21.4%), and weight loss (14.3%). Associated conditions were a history of therapy-resistant pyelonephritis (57.1%), renal stone (28.6%), and recurrent pyelonephritis (14.3%). Laboratory abnormalities included leukocytosis (57.1%), anemia (57.1%), pyuria (57.1%), and impaired renal function (7.1%). Urine culture was positive in 4 children with Proteus mirabilis and in 1 child with Escherichia coli. However, 2 children with negative results had a previous medication history at another institution (Table 1). Intravenous urography showed renal pelvis and calyceal change, non-visualization of nephrogram, and renal calculi. Ultrasonography demonstrated kidney enlargement, hydronephrosis, and pyelonephrosis. Computed tomography (CT) showed low attenuated parenchymal lesion with rim enhancement, renal calculi, perirenal inflammatory lesion, and renal mass (Table 2). The type of XGP that was diagnosed based on preoperative radiologic studies was the focal form in 9 children and diffuse form in 5 children. The preoperative diagnoses included Wilms' tumor in 4 children, renal cell carcinoma in 3, renal abscess in 3, ureteropelvic junction obstruction in 2, and XGP in 2 children (Table 1). Total nephrectomy was performed in 13 children, and conservative medical therapy was administered to one child, who was treated with intravenous antibiotic therapy after admission. After the preoperative diagnosis, percutaneous biopsy of the renal mass was performed. The biopsy specimen showed many characteristic foamy lipid-laden macrophages of XGP. Clinical features, such as palpable mass, anemia, renal calculi, and non-visualization of the kidney, on intravenous urography were more prominent in the diffuse type. Solitary renal mass on ultrasonography or CT were more frequently found in the focal type (Table 3).

XGP is an uncommon form of chronic renal parenchymal infection. Although the focal form may be mistaken for renal cell carcinoma, the more commonly seen diffuse form has characteristic imaging features.1,11 XGP is a rare atypical form of chronic pyelonephritis, characterized by destruction of the renal parenchyma, which is replaced by granulomatous tissue containing lipid-laden macrophages.12 The initial description of the pathologic features of XGP was published in 1916 by Schlagenhaufer. In 1934, Putschar introduced the term, XGP. Many theories on the cause of XGP have been proposed and include urinary tract obstruction, infection (with pathogens Proteus mirabilis and Escherichia coli), and altered metabolism. However, the exact etiology is not clearly understood.11,13,14 XGP predominantly affects middle-aged women, although infants and very old men are also affected. Approximately 70% of adult patients are women.10,15 In children, XPG is rare, and only 265 cases have been reported in the literature worldwide.3 Only 14 cases have been diagnosed in Korean children, including 9 boys and 5 girls. Symptoms of XGP are usually non-specific. The most commonly reported symptoms are fever, abdominal and/or flank pain, weight loss, malaise, anorexia, and symptoms of lower urinary tract infection.16 Clinically, Samuel, et al.11 reported that most children present with flank pain and high fever, and Levy, et al.17 reported that most common symptoms in children included fever, abdominal and/or flank pain, weight loss, malaise, anorexia, and lower urinary tract symptoms. Similarly, the most common findings in Korean children were flank pain and high fever (Table 3). The most common physical examination findings included palpable mass, and no single radiologic feature was diagnostic. In children, the differential diagnoses include Wilms' tumor, neuroblastoma, clear cell carcinoma, and inflammatory processes such as pyelonephrosis, renal tuberculosis, and renal abscess.2,11 XGP should be suspected when there is a history of recurrent or therapy-resistant pyelonephritis and presence of renal calculi, anemia, and leukocytosis. The most commonly reported clinical characteristics in the Korean literature were fever, abdominal pain, anemia, leukocytosis, pyuria, palpable renal mass, and stone. The right kidney was the dominantly affected side (Table 1). Table 3 shows the clinical features of diffuse and focal xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Palpable mass, renal calculi, non-visualization of kidney on intravenous urography, and anemia were more frequently encountered in the diffuse type than in the focal group. In children, the clinical features and laboratory findings of XGP resemble those of chronic pyelonephritis more closely than in adults.5 The histopathologic process is diffuse, involving the whole kidney in 92% and focally confined in 8%.11 The diffuse form of the condition in children occurs equally in boys and girls, and the focal variant occurs more commonly in girls (83%). The female to male ratio of 2.7-4.5 : 1 is observed in adults.5,11 However, the Korean data showed that 35.7% of cases were of the diffuse type, and 64.3% were the focal type. The female to male ratio in the diffuse type was 0.25 : 1 and 0.8 : 1 in the focal type. According to these ratios, a higher incidence of XGP is observed in males (Table 3). Recently, increasingly sensitive radiologic investigations (ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging) in combination with clinical suspicion have made preoperative diagnosis possible.18 Ultrasonography can demonstrate enlargement of the entire kidney with multiple hypoechoic areas representing hydronephrosis and calyceal dilatation with parenchymal destruction as well as calculi. However, acoustic shadowing is an unpredictable finding and may be masked by peripelvic fibrosis. In particular, an atypical sonographic appearance is indistinguishable from some renal parenchymal diseases.19,20 CT remains the most appropriate radiologic investigation. Typically, the disease is diffuse, and a renal calculus may be seen in a contracted renal pelvis of an enlarged kidney, with characteristic low-attenuation and peripherally enhancing rounded masses with rim enhancement.1,21,22 Extrarenal extension of the inflammatory process is frequently seen. Less commonly, the process is confined focally and difficult to differentiate from malignant disease on radiologic studies.21 According to the Korean data, preoperative diagnoses in 5 children with diffuse type XGP included ureteropelvic junction obstruction (2 children), renal cell carcinoma (1 child), renal abscess (1 child), and XGP (1 child). The preoperative diagnoses of 9 children with focal type XGP were Wilms' tumor (4 children), renal cell carcinoma (2 children), renal abscess (2 children), and XGP (1 child) (Table 1). In children, it is important to ascertain the diagnosis before reaching a therapeutic decision. A trial of antibiotic therapy or nephron sparing surgery should be considered. However, correct preoperative diagnosis in Korean children was made in only 2 cases (Table 1). The treatment of choice for diffuse XGP is nephrectomy and excision of the involved surrounding tissue, and the treatment for focal XGP is partial resection or enucleation after a trial of medical management if indicated. However, focal XGP may be incorrectly interpreted as renal cell carcinoma. Therefore, thorough follow-up and monitoring are necessary.23-25 Only 1 child among 14 children identified in the Korean data was treated with conservative medical therapy alone, and follow-up CT showed complete resolution of the renal mass (Fig. 1). However, due to the limited number of cases reported, the multicenter data, retrospective nature of the study, and limited quantity of data available (for example, nuclear scan test can examine the function of each kidney, however, not done in all cases), our review needs further validation.

XGP in children is a rare condition, and preoperative diagnosis, especially of the focal type, remains challenging. However, if a renal mass, particularly one of small size, is associated with fever, malaise, or flank tenderness, one should consider the possibility of XGP. Since focal XGP commonly presents with a renal mass and is difficult to differentiate from renal tumor, ultimate efforts, such as percutaneous renal biopsy, should be made to establish the diagnosis. Once an early diagnosis is made, the prognosis may be excellent following appropriate management.

In conclusion, XGP in children is a rare condition, and preoperative diagnosis is very important. Increasingly, sensitive radiologic investigations, such as ultrasonography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging, in combination with clinical suspicion have made preoperative diagnosis possible. However, focal XGP may be misdiagnosed as renal malignant disease. If a child presents with a renal mass, particularly a small-sized solitary mass, that is associated with recurrent or therapy resistant urinary tract infection, fever, leukocytosis, or renal stone, the possibility of XGP should be considered.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Case of child treated with conservative medical therapy alone. (A) Enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen shows hypoattenuating mass in the right kidney. (B) Follow-up computed tomography 2 weeks later shows that the renal mass decreased in size.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital Research Grant.

References

1. Hammadeh MY, Nicholls G, Calder CJ, Buick RG, Gornall P, Corkery JJ. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in childhood: pre-operative diagnosis is possible. Br J Urol. 1994. 73:83–86.

2. Parsons MA, Harris SC, Longstaff AJ, Grainger RG. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: a pathological, clinical and aetiological analysis of 87 cases. Diagn Histopathol. 1983. 6:203–219.

3. Hendrickson RJ, Lutfiyya WL, Karrer FM, Furness PD 3rd, Mengshol S, Bensard DD. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. J Pediatr Surg. 2006. 41:e15–e17.

4. Ahn SY, Kim CC, Cho JH. A case of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in child. Korean J Urol. 1977. 18:541–544.

5. Jung GW, Jeong MK, Yoon JB. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in childhood: a case report. Korean J Urol. 1986. 27:911–914.

6. Jeong KS, Kim DS, Cho JH. A cases of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in children. Korean J Urol. 1994. 35:82–85.

7. Chung HS, Hwang JC, Suh HJ, Jung SY, Baek YK. Bilateral xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in a child. Korean J Urol. 1996. 37:98–100.

8. Yim SB, Kwon CK, Lee JH, Shin JS, Yim JS, Hwang MH, et al. A case of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in children. Korean J Urol. 1997. 38:1117–1120.

9. Choi SH, Lee JH, Cho SR. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in a child. Korean J Urol. 2005. 46:1231–1234.

10. Lee HN, Kim KH, Ryu IW, Han MC, Chung WS. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in an infant. Korean J Urol. 2006. 47:1367–1370.

11. Samuel M, Duffy P, Capps S, Mouriquand P, Williams D, Ransley P. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 2001. 36:598–601.

12. Sugie S, Tanaka T, Nishikawa A, Yoshimi N, Kato K, Mori H, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Urology. 1991. 37:376–379.

13. Petronic V, Buturovic J, Isvaneski M. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Br J Urol. 1989. 64:336–338.

14. Tolia BM, Iloreta A, Freed SZ, Fruchtman B, Bennett B, Newman HR. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: detailed analysis of 29 cases and a brief discussion of atypical presentations. J Urol. 1981. 126:437–442.

15. Anhalt MA, Cawood CD, Scott R Jr. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: a comprehensive review with report of 4 additional cases. J Urol. 1971. 105:10–17.

16. Kural AR, Akaydin A, Oner A, Ozbay G, Solok V, Oruc N, et al. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in children and adults. Br J Urol. 1987. 59:383–385.

17. Levy M, Baumal R, Eddy AA. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in children. Etiology, pathogenesis, clinical and radiologic features, and management. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1994. 33:360–366.

18. Zugor V, Schott GE, Labanaris AP. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in childhood: a critical analysis of 10 cases and of the literature. Urology. 2007. 70:157–160.

19. Hartman DS, Davis CJ Jr, Goldman SM, Isbister SS, Sanders RC. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: sonographic--pathologic correlation of 16 cases. J Ultrasound Med. 1984. 3:481–488.

20. Tiu CM, Chou YH, Chiou HJ, Lo CB, Yang JY, Chen KK, et al. Sonographic features of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001. 29:279–285.

21. Kim JC. US and CT findings of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Clin Imaging. 2001. 25:118–121.

22. Kenny PJ. Pollack HM, McClennan BL, Dyer R, editors. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Clinical Urography. 2000. Vol. 1:2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;952–962.

23. Marteinsson VT, Due J, Aagenaes I. Focal xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis presenting as renal tumour in children. Case report with a review of the literature. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1996. 30:235–239.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download