Abstract

This report describes a 6 year-old boy who was treated with one-bone forearm procedure for acquired pseudoarthrosis of the ulna combined with radial head dislocation after radical ulna debridement for osteomyelitis. At more than 20 years of follow-up, the patient had a nearly full range of elbow movements with a few additional surgical procedures. Pronation and supination was restricted by 45°, but the patient had near-normal elbow and hand functions without the restriction of any daily living activity. This case shows that one-bone forearm formation is a reasonable option for forearm stability in longstanding pseudoarthrosis of the ulna with radial head dislocation in a child.

Bony defects of the ulna secondary to congenital deformity, osteomyelitis, trauma, or tumor resection may result in significant functional deficits and deformities if left untreated,1 and several surgical options have been reported such as simple internal fixation and bone grafting, structural or vascularized bone grafting with internal fixation, bone lengthening with distraction osteogenesis, and the forma-tion of a one-bone forearm.2,3

A 6 year-old boy presented with the chief complaint of slowly progressing left elbow deformity and instability. As an infant, the patient underwent extensive ulna debridement secondary to acute osteomyelitis at another hospital. On a physical examination, the patient had a cubitus varus deformity of 19° at the elbow, a palpable dislocated radial head at the anterior elbow, and significant forearm instability. The range of movement of the elbow was -10° to 130°; pronation/supination was 30°/30°. The forearm length was about 4 cm shorter than the other.

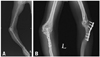

Radiographs (Fig. 1) revealed pseudoarthrosis of the ulna with functional ulnohumeral and radiocarpal joints, an atrophic distal ulna, an anterolateral dislocation of the radial head, and lateral bowing of the radius.

The surgical technique used was as previously described by Castle.4 A osteotomy level on the radius was selected so that the length would equal that of the other forearm after making a one-bone forearm. In neutral supination-pronation, a Kirschner wire was inserted from the tip of the olecranon. The proximal fragment of the radius was left at the initial operation. Bony union was observed approximately 1 year after the one-bone forearm procedure with secondary bone grafting. Three months later, the proximal fragment of the radius was removed and the biceps tendon was transferred to the insertion site of the brachialis tendon to preserve active flexion.

Eighteen and a half years after the one-bone forearm procedure, the patient presented with a cubitus valgus deformity (carrying angle, 45°) (Fig. 2). A corrective dome osteotomy at the proximal metaphysis of the ulna was performed. At a 20 years and 3 months follow-up, the patient carrying angle was about 10°. There was no instability at the elbow or wrist. The elbow range of movement was -7° to 141°; pronation/supination was 40°/40° (Fig. 3). The wrist range of movement was 70° of flexion, 80° of extension, 30° of radial deviation, and 50° of ulnar deviation. There was no limb shortening. Grip and pinch strengths on the affected side were 30 kg and 7 kg, which were 60% and 78% of that on the unaffected side. The patient reported a nearly normal functional capacity with the ability to perform all activities of daily living. On the Peterson and colleagues scoring system, which assigns points to function, pain, and attainment of union, the patient scored a 10, the highest score.

Bony defects of the ulna, if left untreated, can result in significant forearm deformity, including radial head dislocation, instability of the elbow, radial nerve neuropathy, and cubitus varus deformity.1 Indications for conversion to a one-bone forearm include significant, symptomatic, angular, axial, or rotator radioulnar instability in the setting of segmental bone loss or refractory nonunion.3 A normal hand, a reasonably good proximal end of the ulna and distal end of the radius, and functional ulnohumeral and radiocarpal joints are critical to this procedure.4 Also, in our case, longstanding radial head dislocation and dysplastic change of the distal ulnar fragment were combined with pseudoarthrosis of the ulna. Longstanding radial head dislocation in the skeletally immature patient causes dysplastic changes in not only the proximal radioulnar joint, but also the distal humerus, not unlike the changes seen in the developmental dislocation of the hip.5-7

Watson-Jones8 was the first to recommend a rotational position of 10 pronation for fusion in the one-bone forearm procedure. Other reports have recommended varying degrees of rotation from 45° of supination, neutral rotation, to pronation.3,4,8,9 Generally, fusion in supination confers better activities toward the body, whereas fusion in pronation makes activities away from the body easier.10 Compensation from shoulder and wrist joints should be contemplated. In particular, shoulder abduction and internal rotation can facilitate activities that need more forearm supination.8,11 Preoperative trial bracing may be useful to allow informed patient choice regarding position.3 However, it might not be proper to use trial bracing in children. As a result, in the present case, a neutral rotation of fusion was chosen after discussing the treatment with the patient parents, and this position allowed 40°/40° of pronation/supination with no difficulties for more than 20 years of. The motion of pronation/supination might not be from forearm rotation but from compensatory movement of the wrist joint resembling a ball and socket joint (Fig. 2). This compensatory movement cannot be expected when the procedure is performed in adults.

There are mixed results of one-bone forearm procedures according to previous reports.3,4,8,9 In the largest series to date, Peterson, et al.3 report 59% good to excellent, 26% fair, and 5% poor results in their series of 19 one-bone forearm procedures. Poor results were related to previous trauma, infection, severe nerve injury, and multiple previous surgical procedures. Recently, pediatric case reports have noted the successful use of radioulnar fusion, especially when combined with radial head dislocation, as a primary or salvage procedure in congenital pseudoarthrosis either idiopathic in nature or secondary to neurofibromatosis, as the procedure that could preserve both proximal and distal physes of the new forearm bone.12-14

This case shows that the one-bone forearm procedure at a neutral rotation position can be a successful treatment for pseudoarthrosis of the ulna combined with long standing radial head dislocation in a child with a long-term follow-up, even if there are some complications, which can be overcome by proper surgical intervention.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the left forearm of a 6-year-old boy with left elbow deformity and shortening show a pseudoarthrosis of the ulna and atrophic change of the distal ulna with a chronic radial head dislocation.

References

1. Kitano K, Tada K. One-bone forearm procedure for partial defect of the ulna. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985. 5:290–293.

2. Morrey BF, Askew LJ, Chao EY. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981. 63:872–877.

3. Peterson CA 2nd, Maki S, Wood MB. Clinical results of the one-bone forearm. J Hand Surg Am. 1995. 20:609–618.

4. Castle ME. One bone forearm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974. 56:1223–1227.

5. Chambers HG, Wilkins KE. Rockwood CA, Wilkins KE, Beaty JH, editors. Dislocation of the head of the radius. Fractures in Children. 1996. Philadelphia, New York: Lippincott-Raven;873–878.

6. Fowles JV, Sliman N, Kassab MT. The Monteggia lesion in children. Fracture of the ulna and dislocation of the radial head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983. 65:1276–1282.

7. Lloyd-Roberts GC, Bucknill TM. Anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: etiology, natural history, and management. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1977. 59:402–407.

8. Wason-Jones R. Reconstruction of the forearm after loss of the radius. Br J Surg. 1934. 22:23–26.

9. Lowe HG. Radioulnar fusion for defects in the forearm bones. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1963. 45:351–359.

10. Helm RH, Pho RW, Tonkin MA. The sequelae of osteomyelitis of the proximal ulna occurring in early childhood. J Hand Surg Br. 1992. 17:232–234.

11. Simmons BP, Southmayd WW, Riseborough EJ. Congenital radioulnar synostosis. J Hand Surg Am. 1983. 8:829–838.

12. Bell DF. Congenital forearm pseudoarthrosis: report of six cases and review of literature. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989. 9:438–443.

13. Cheng JC, Hung LK, Bundoc RC. Congenital pseudoarthrosis of the ulna. J Hand Surg Br. 1994. 19:238–243.

14. Durga Nagaraju K, Vidyadhara S, Raja D, Rajasekaran S. Congenital pseudoarthrosis of the ulna. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2007. 16:150–152.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download