Abstract

Congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia (CLAH) is caused by mutations to the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene associated with the inability to synthesize all adrenal and gonadal steroids. Inadequate treatment in an infant with this condition may result in sudden death from an adrenal crisis. We report a case in which CLAH developed in Korean siblings; the second child was prenatally diagnosed because the first child was affected and low maternal serum estriol was detected in a prenatal screening test. To our knowledge, this is the first prenatal diagnosis of the Q258X StAR mutation, which is the only consistent genetic cluster identified to date in Japanese and Korean populations.

Congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia (CLAH) is the most severe form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia in which the synthesis of all adrenal and gonadal steroid hormones is impaired, due to mutations to the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene.1 Clinical findings in these patients are salt loss, hypoglycemia, pigmentation and male sex reversal. Delay in treatment may result in sudden death from adrenal crisis. While the homozygous c.201-202 delCT StAR mutation has been prenatally diagnosed in Palestinians, this is the first prenatal diagnosis of the Q258X StAR mutation, which is the only consistent genetic cluster identified to date in Japanese and Korean populations.2-7

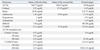

A 33-year-old G2P1 woman presented to our obstetric unit at 17 weeks' gestation for antenatal care of her second pregnancy. Maternal serum screening demonstrated a very low estriol level of 0.06 multiples of the median (MoM) with low alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level, 0.6 MoM and 0.52 MoM, respectively, which were interpreted as a high risk of Edward syndrome (1 : 79) and Smith-Lemli-Opitz (SLO) syndrome (1 : 7).8,9 The karyotype by amniocentesis was 46,XX. Level II ultrasonography after 21 weeks' gestation demonstrated no structural abnormalities including the adrenal glands and genitalia. Upon reevaluation of family history, however, the parents revealed that their 27-month-old first baby had been diagnosed with CLAH. The first baby was delivered vaginally at 36+2 weeks' gestation with birth weight 2,360 g. Initial symptoms included projectile vomiting and poor oral intake, with lethargy and hyperpigmentaion 10 weeks after birth. The initial laboratory finding demonstrated hyponatremia (125 mEq/L) and hyperkalemia (6.6 mEq/L). Basal adrenal hormone levels and an adrenocoticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test showed a severe deficiency of adrenal hormones (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated diffusely enlarged adrenal glands with markedly low density. Gene analysis revealed a normal CYP21A2 gene sequence but a homozygous mutation c.772C>T in exon 7 of StAR. She was diagnosed with CLAH and treated with stress doses of hydrocortisone and 1036mineralocorticoid, which were tapered to a maintenance dose.

Therefore, prenatal testing was performed in the second sibling for the relevant disease-causing mutation from fetal cells by amniocentesis. Exon 7 and its adjacent intronic sequences were amplified by PCR, using forward primer 5'-CCTGGCAGCCTGTTTGTGATAG-3' and reverse primer 5'-ATGAGCGTGTGTACCAGTGCAG-3', which revealed a homozygous c.772C>T substitution resulting in a glycine to stop codon substitution at amino acid 258 (Fig. 1). A 2,665 g female baby was delivered vaginally with Apgar scores of 7 and 9 at 40 weeks' gestation. At birth, the baby presented with normal female external genitalia. Screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia was normal, 17α-OH progesterone (17α-OHP) 8.33 ng/mL (normal 1.7-25.0 ng/mL). There were no clinical signs or symptoms until 3 months after birth. Four months after birth, the second baby was admitted to our hospital with vomiting and diarrhea after DTaP vaccination. Her laboratory profile was similar to that of her sister, but without enlargement of adrenal glands on ultrasonography (Table 1). Genetic evaluation from the peripheral blood confirmed the same mutation. She was diagnosed with CLAH and discharged on the 9th day of hospitalization after treatment of mineralocorticoid and hydrocortisone.

The maternal screening test during the second trimester is a combined serum analysis for the prenatal detection of Down syndrome, Edward syndrome, Patau syndrome, and open neural-tube defects.8 The screening test measures the levels of AFP, hCG, unconjugated estriol, and inhibin A.

Interestingly, this case showed low levels of AFP and hCG, with very low levels of unconjugated estriol. The most common cause of extremely low estriol levels is steroid sulfatase deficiency, the prenatal manifestation of X-linked recessive ichthyosis, which affects 1 in 3,000 males, and SLO syndrome, which affects 1 in 15,000 to 20,000 and is caused by mutations in the gene encoding 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7).9-11 These two conditions need to be ruled out by checking the levels of steroid sulfatase activity in the amniotic cell culture and amniotic-fluid DHCR7, respectively. When there is no evidence of maternal virilization during pregnancy, as in our case, it is unlikely suspicious of placental aromatase deficiency.12

During pregnancy, estriol is derived almost exclusively from placental aromatization of the fetal adrenal steroid dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS). Therefore, low estriol levels in the context of normal fetal sonography and growth should raise suspicion of deficient fetal steroidogenesis, which results in decreased production of adrenal DHEAS.9-11 Fetal adrenal insufficiency can be caused by a mutation in the gene encoding the StAR protein. The role of StAR protein is facilitating transport of cholesterol into the mitochondria and the mutation in the gene encoding this protein results in lipoid adrenal hypoplasia or 17-hydroxylase deficiency.1,13,14 Although these entities are associated with XY gender reversal, our case was a female and there were no abnormal findings of the genitalia upon prenatal and postnatal examination. Other possibilities include X-linked congenital adrenal hypoplasia, resistance to ACTH, and secondary adrenal insufficiency, either isolated or as part of multiple pituitary hormone deficiency.15-17 Our observation of extremely low estriol levels during pregnancy as a predictor of CLAH suggests that each case of extremely low estriol detected by the maternal screening test should be reevaluated. First, any family history of disordered steroidogenesis should be sought, followed by a detailed prenatal ultrasonography looking for the characteristic features of SLO syndrome before invasive tests, if required.12

Due to the difficulty of establishing a diagnosis of CLAH from amniotic hormone assays, molecular genetic testing is often needed.2,14 It is important that infants born to mothers with low estriol levels of unexplained causes should be evaluated postnataly, as soon as possible, to rule out adrenal insufficiency. Also, the affected patients should be closely monitored in the outpatient clinic, because the majority of patients present during the first few months of life with hyponatremia and adrenal crisis.8

Prenatal molecular genetic diagnosis of CLAH might be effective in Korean or Japanese families with the known StAR mutations, as well as in families with a 46,XY karyotype but female genitalia on ultrasound and/or low maternal serum estriol levels, in order to prevent future neonatal deaths due to undiagnosed CLAH. Further prospective studies with larger populations are needed to determine whether this would be useful.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Miller WL. Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), a novel mitochondrial cholesterol transporter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007. 1771:663–676.

2. Jean A, Mansukhani M, Oberfield SE, Fennoy I, Nakamoto J, Atwan M, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia (CLAH) by estriol amniotic fluid analysis and molecular genetic testing. Prenat Diagn. 2008. 28:11–14.

3. Lin D, Sugawara T, Strauss JF 3rd, Clark BJ, Stocco DM, Saenger P, et al. Role of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in adrenal and gonadal steroidogenesis. Science. 1995. 267:1828–1831.

4. Bose HS, Sato S, Aisenberg J, Shalev SA, Matsuo N, Miller WL. Mutations in the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in six patients with congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000. 85:3636–3639.

5. Nakae J, Tajima T, Sugawara T, Arakane F, Hanaki K, Hotsubo T, et al. Analysis of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene in Japanese patients with congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. Hum Mol Genet. 1997. 6:571–576.

6. Yoo HW, Kim GH. Molecular and clinical characterization of Korean patients with congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1998. 11:707–711.

7. Bose HS, Sugawara T, Strauss JF 3rd, Miller WL. International Congenital Lipoid Adrenal Hyperplasia Consortium. The pathophysiology and genetics of congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1996. 335:1870–1878.

9. Palomaki GE, Bradley LA, Knight GJ, Craig WY, Haddow JE. Assigning risk for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome as part of 2nd trimester screening for Down's syndrome. J Med Screen. 2002. 9:43–44.

10. Bartels I, Caesar J, Sancken U. Prenatal detection of X-linked ichthyosis by maternal serum screening for Down syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1994. 14:227–229.

11. Opitz JM, Gilbert-Barness E, Ackerman J, Lowichik A. Cholesterol and development: the RSH ("Smith-Lemli-Opitz") syndrome and related conditions. Pediatr Pathol Mol Med. 2002. 21:153–181.

12. Grumbach MM, Auchus RJ. Estrogen: consequences and implications of human mutations in synthesis and action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999. 84:4677–4694.

13. Auchus RJ. The genetics, pathophysiology, and management of human deficiencies of P450c17. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2001. 30:101–119. vii

14. Saenger P, Klonari Z, Black SM, Compagnone N, Mellon SH, Fleischer A, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995. 80:200–205.

15. Marshall I, Ugrasbul F, Manginello F, Wajnrajch MP, Shackleton CH, New MI, et al. Congenital hypopituitarism as a cause of undetectable estriol levels in the maternal triple-marker screen. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003. 88:4144–4148.

16. Hensleigh PA, Moore WV, Wilson K, Tulchinsky D. Congenital X-linked adrenal hypoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 1978. 52:228–232.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download