Abstract

Long QT syndrome is associated with lethal tachyarrhythmia that can lead to syncope, seizure, and sudden death. Congenital long QT syndrome is a genetic disorder, characterized by delayed cardiac repolarization and prolongation of the QT interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG). Type 2 congenital long QT is linked to mutations in the human ether a go-go-related gene (HERG). There are environmental triggers of adverse cardiac events such as emotional and acoustic stimuli, but fever can also be a potential trigger of life-threatening arrhythmias in long QT syndrome type 2 patients. Herein, we report a healthy young man who experienced fever-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and QT interval prolongation.

Congenital long QT syndrome is a genetic disorder associated with ventricular arrhythmias. Mutations in a gene-encoding cardiac ion channel affect the cardiac action potential that plays an important role in cardiac repolarization. Delayed cardiac repolarization and development of QTc prolongation can lead to cardiac events. Recognized triggers of these cardiac events include physical exercise, and emotional and acoustic stimuli. Recently, it was reported that fever can accentuate transmural dispersion of repolarization and facilitate development of early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes under long QT conditions in animal models.1,2 Although the relationship between fever and ion channel disorder is well known in patients with Brugada syndrome, it is not known whether fever can also aggravate cardiac event in long QT syndrome.3 This report reviews a case of a healthy young man who presented with sudden cardiac death syndrome and was later diagnosed with long QT syndrome accompanied by fever.

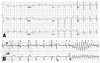

A 26-year-old man with no past medical history was found with agonal breathing, followed by generalized convulsions while sleeping. When he arrived at the emergency department, the ECG revealed asystole. After cardiopulmonary resuscitation with 8 defibrillations, the ECG recovered to a sinus rhythm. He had no family history of sudden cardiac death. His father had undergone a coronary artery bypass graft surgery due to myocardial infarction 1 year ago. The patient's past history was not significant for any medication or illicit drugs. Cardiac enzymes were elevated and the levels were consistent with post-cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) status. His laboratory findings showed no electrolyte abnormalities. Echocardiography showed no structural heart disease. Initially, his ECG showed ST depression in limb leads, suggesting ischemic injury after prolonged cardiac arrest. He had fever and leukocytosis with hazziness in the lower lung field suggesting aspiration pneumonia. Fig. 1A shows the ECG taken on the 8th hospital day revealing normal ECG.

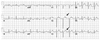

The patient had spontaneous ventricular fibrillation on the 9th hospital day, accompanied by fever of 38.0℃. Fig. 1B shows the spontaneous initiation of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with a short-long-short sequence. In the figure, premature ventricular beats are marked with arrows. QT and QTc intervals were 350 and 450 ms, respectively. Torsades de pointes was terminated with the biphasic shock of 150 J. On the 28th hospital day, he again had a fever of 38.5℃ and sinus tachycardia of 135 bpm. ECG during the fever showed severe QT prolongation with QT and QTc intervals of 365 and 535 ms, respectively (Fig. 2). U-waves were observed in the leads of V5 and V6 (arrows). This finding disappeared 1 hour later with the resolution of fever.

Two months after aborted sudden cardiac death, the patient's condition recovered to wheel chair ambulation, and an examination was performed to reveal the cause of the sudden death. After the infusion of epinephrine (0.1 µg/kg/min), the patient showed prolongation of QT and QTc interval of 430 and 515 ms, respectively (Fig. 3). The prominent U-wave was also observed in leads V2 and 3 (arrows in Fig. 3). Other tests, including a flecainide infusion test, a coronary angiography with provocation of acetylcholine test, and an electrophysiologic study, showed normal findings. The patient was diagnosed with long QT type 2 syndrome, which was manifested by fever, and received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator and oral beta blocker.

Long QT syndrome is an inherited arrhythmogenic disease characterized by susceptibility to life-threatening polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation. Syncope and fainting, seizure, but also cardiac arrest and sudden death, are the typical manifestations of long QT syndrome. Their occurrence is often precipitated by gene-specific triggers (e.g., fear, anger, loud noises, sudden awakening), but they may also occur at rest. Lethal events occur during auditory stimuli and emotional stress in long QT syndrome type 2 patients.4,5 However, fever was not reported as a trigger of cardiac events in long QT syndrome.6 A recent clinical study has demonstrated that fever can be a risk factor for the development of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in the long QT syndrome type 2. Amin, et al.7 demonstrated fever-induced QT interval prolongation in patients with mutation of the A558P human ether a go-go-related gene (HERG) that encodes the α subunit for the delayed rectifier K current (I kr). A558P mutation affects the HERG channel function in a temperature-dependent manner, so that the elevation of temperature (up to 40℃) induces prolongation of action potential and triggers early afterdepolarizations (EADs). EADs are associated with the initiation of torsades de pointes. The ECG of the present patient showed the typical pattern of long QT syndrome type 2. The two most frequently encountered ECG manifestations of long QT syndrome type 2 are bifid T waves. This patient showed obvious bifid T waves (Fig. 3) and subtle bifid T waves with a second component on top of the T wave in limb and left precordial leads (Fig. 2). We could not confirm the genotype because we did not perform genetic testing. Although genetic testing may provide additional information, the rationale is often debatable. The Schwartz scoring system is widely used in clinical practice, and clinical diagnosis suggests the gene affected in 70-90% of patients.8 For those patients who meet clinical criteria for long QT syndrome, genotype may provide little benefit. As a result of genetic heterogeneity (mutations in unknown genes), -25% of long QT syndrome families do not have abnormalities on screening of the known genes.9 In contrast to the controversial genetic study, however, a combination of quantified ECG repolarization parameters can identify genotype with sensitivity/specificity of 85%/70% for type 1, 83%/94% for type 2, and 47%/63% for type 3 long QT syndrome.10,11 Fever-related arrhythmias is commonly reported in Brugada syndrome, which is caused by sodium channel mutation.12-14 However, this patient showed no evidence of Brugada syndrome in repeated provocation test with sodium channel blocker and continuous ECG monitoring for 30 days.

In conclusion, both environmental and genetic susceptibility factors interact to induce long QT syndrome. This case is expected to serve as an impetus for further studies examining the role of pyrexia as a risk factor for the development of long QT syndrome.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) ECG taken on the 8th hospital day. QT and QTc intervals were 350 and 440 ms, respectively. (B) ECG taken on the 9th hospital day showing spontaneous onset of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia by the short-long-short sequences. Arrows indicate the premature ventricular contractions. QT and QTc intervals were 350 and 450 ms, respectively. ECG, electrocardiogram.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Korean Healthcare Technology Research and Development Grant (number A085136) and the faculty research grant (6-2009-0176) of Yonsei University College of Medicine.

References

1. Burashnikov A, Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Fever accentuates transmural dispersion of repolarization and facilitates development of early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes under long-QT Conditions. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008. 1:202–208.

2. Pasquié JL, Sanders P, Hocini M, Hsu LF, Scavée C, Jais P, et al. Fever as a precipitant of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation in patients with normal hearts. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004. 15:1271–1276.

3. Guo J, Zhan S, Lees-Miller JP, Teng G, Duff HJ. Exaggerated block of hERG (KCNH2) and prolongation of action potential duration by erythromycin at temperatures between 37 degrees C and 42 degrees C. Heart Rhythm. 2005. 2:860–866.

4. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Napolitano C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation. 2001. 103:89–95.

5. Lee SY, Kim JB, Im E, Yang WI, Joung B, Lee MH, et al. A case of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Yonsei Med J. 2009. 50:448–451.

7. Amin AS, Herfst LJ, Delisle BP, Klemens CA, Rook MB, Bezzina CR, et al. Fever-induced QTc prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias in individuals with type 2 congenital long QT syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2008. 118:2552–2561.

8. Tester DJ, Will ML, Haglund CM, Ackerman MJ. Effect of clinical phenotype on yield of long QT syndrome genetic testing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006. 47:764–768.

9. MacRae CA. Closer look at genetic testing in long-QT syndrome: will DNA diagnostics ever be enough? Circulation. 2009. 120:1745–1748.

10. Roden DM. Long QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008. 358:169–176.

11. Zhang L, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, Lehmann MH, Fox J, Giuli LC, et al. Spectrum of ST-T-wave patterns and repolarization parameters in congenital long-QT syndrome: ECG findings identify genotypes. Circulation. 2000. 102:2849–2855.

12. Kaufman ES. Mechanisms and clinical management of inherited channelopathies: long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and short QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2009. 6:S51–S55.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download