Abstract

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare malignancy with poor prognosis, and it can be classified as either a functional or nonfunctional tumor. Affected patients usually present with abdominal pain or with symptoms related to the mass effect or hormonal activity of the tumor. Several cases of spontaneously ruptured nonfunctional adrenocortical carcinoma have been reported, but no case of a spontaneous rupture of functioning adrenocortical carcinoma has been described. We report a functioning adrenocortical carcinoma that spontaneously ruptured during a work-up.

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare malignant neoplasm with poor prognosis, which arises from adrenal cortical cells. Adrenal cancers can be classified as functional or nonfunctional. Approximately 60% of patients with ACC present with evidence of adrenal steroid hormone excess.1 For non-functioning tumors, the presentation is usually related to tumor size.1 Patients with non-functioning ACCs usually present with abdominal pain or pressure secondary to mass effect. Only a few cases of spontaneously ruptured nonfunctional ACC have been reported in the literature.2-5 However, spontaneous rupture of a functioning ACC has not been described.

We report a rare functioning ACC that spontaneously ruptured during work-up.

A 36-year old woman was admitted to our hospital because of a 10 kg weight gain during the previous 5 months and a left adrenal mass incidentally detected on abdominal ultrasonographic examination at another hospital. She had undergone total mastectomy due to right breast cancer (stage I) 10 months before admission and was receiving goserelin on a monthly basis. She had a moon face and a mild buffalo hump.

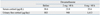

The chest radiography, routine hematology and biochemistry were unremarkable. The endocrine examination showed elevated serum cortisol, suppressed plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone, and loss of circadian rhythm (Table 1). The serum cortisol level and the urinary free cortisol excretion were not reduced after 2-mg and 8-mg dexamethasone suppression tests (Table 2).

Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen revealed a 12×10.3×9.7 cm sized, heterogeneous mass in the left adrenal gland, with possible internal hemorrhagic necrosis (Fig. 1). Whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) images showed significant 18F-FDG uptake in the huge left adrenal mass and no significant uptake at any other sites.

On the basis of the physical findings, endocrine data, and imaging studies, the patient was diagnosed with Cushing's syndrome secondary to an ACC. We scheduled an elective operation to remove the mass. However, the patient complained of sudden onset of left upper quadrant abdominal pain. An abdominal CT showed that the tumor mass in the adrenal gland had increased in size and that there was a hemorrhagic fluid collection in the left perinephric area. These findings were suggestive of a tumor rupture (Fig. 2). We performed a left adrenalectomy using an open transabdominal approach. The adrenal tumor was found to have ruptured, and the resected tumor, weighing 251 g, was internally hemorrhagic and necrotic. Histological examination of the specimen revealed an adrenal cortical carcinoma (Fig. 3A and B). The histological findings fulfilled three of the modified Weiss's criteria for histopathological diagnosis of adrenocortical carcinoma with a total score of 4 (threshold score ≥ 3):6 The presence of ≤ 25% clear tumor cells, the presence of necrosis, and capsular invasion. Immunohistochemical examination showed positive labeling of neoplastic cells with synaptophysin, CD56, alpha-inhibin, and melan-A (Fig. 3C-F), while tumor cells did not express cytokeratin, S-100 protein, chromogranin A, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and c-erbB2 (not shown). The patient was classified with more than stage III due to tumor spillage according to the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENSAT) staging classification.7

Replacement therapy with hydrocortisone (20-mg) was initiated, and the patient received adjunctive chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine). However, the 3-month follow-up abdominal CT demonstrated a recurred lesion in the left perirenal area. Therefore, the patient was started on adjuvant chemotherapy, including etoposide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin.

ACC is a rare malignancy, with an annual incidence of approximately 1-2 persons per one million people.8 ACCs can be classified as functional when their hormonal secretions result in clinical manifestations such as Cushing syndrome, virilization syndrome, feminization syndrome, or a mixed Cushing-virilizing syndrome. Tumors are considered nonfunctional when the tumors do not secrete excessive hormones or produce hormones in quantities sufficient to result in clinical consequences.1,8 Patients with nonfunctioning tumors usually present with abdominal pain or pressure secondary to the mass effect of the large tumor. Approximately 60 percent of ACCs are functioning tumors, with excessive cortisol secretion seen in approximately 30% of functioning tumors: androgen hypersecretion in 20%, estrogen hypersecretion in 10%, and aldosterone hypersecretion in 2%.1,8 Thirty-five percent of functioning ACCs secrete multiple hormones. Because many steroid enzymes are defective in the setting of ACC, which leads to inefficient steroid production, several steroids are elevated in Cushing's syndrome due to functioning ACC, including dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfate derivative DHEA-S as well as urinary 17-ketosteroid and 17-hydroxycorticosteroids. Thus, a high serum DHEA-S concentration is suggestive of ACC, whereas a low serum DHEA-S concentration is suggestive of a benign adenoma.9 In the current case, the serum ACTH was reduced, the serum cortisol level and urinary free cortisol excretion were not suppressed after 2-mg and 8-mg dexamethasone suppression tests, and the serum DHEA-S and urinary 17-KS concentrations were high. Thus, endocrine data were consistent with Cushing syndrome associated with ACC.

Tumor rupture is a rare event.2 To date, spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhages have been reported as the prevalent presentation in other adrenal tumors, such as metastases, adenoma, myelolipoma, and pheochromocytoma.10,11 Only several cases of a spontaneous rupture of nonfunctional ACCs have been reported in the literature.2,5 However, to our knowledge, spontaneous ruptures of a functional ACC have not been described before. The cause of ACC ruptures is unknown. It may be related to tumor size, necrosis caused by rapid tumor growth, rapid expansion of the tumor secondary to an internal hemorrhage, and delay in diagnosis.2,5 Similarly, in some cases of the rupture of nonfunctioning adrenal adenoma, the tumor was large in size despite being a benign tumor.12,13 Often, the general health of patients with nonfunctional ACC is preserved, except at a very late stage, leading to a delay in diagnosis.14,15 However, clinical manifestations in a functional tumor may result in relatively early detection of a tumor, and it may be related to a lower incidence of ruptures in functional ACC than in nonfunctional ACC. It is unknown whether the cortisol-producing process is related to ruptures. Thus, additional investigations to evaluate what is involved in the rupture of functioning ACC are needed.

A fine needle biopsy is often used for diagnostic purposes in patients with a known extra-adrenal malignancy who have been shown to have an adrenal mass.16 The present patient had a history of primary breast cancer. However, the fine needle biopsy is not free of complications. Thus, we did not perform a fine needle biopsy; the patient had clinical characteristics of cortisol excess, and there was no evidence of recurring breast cancer. Regarding the association with other tumors, Venkatesh, et al.17 reported that 13 out of 100 patients with adrenal carcinoma had a second primary tumor. The most frequent second primary tumors appeared to be breast carcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, and melanoma.

The current patient had a Cushingoid appearance and a large mass in the left adrenal gland. Endocrine and imaging examination were consistent with Cushing syndrome due to an ACC. While the patient was waiting for surgery, she developed left upper quadrant abdominal pain. Imaging studies showed a hemorrhage in the tumor and retroperitoneum.

Our case suggests that a spontaneous rupture of an ACC should be considered in patients who develop abdominal pain during the diagnostic work-up and in those whose pain changes, even though a rupture rarely occurs.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Adrenal T1 MRI showed an approximately 12×10.3×9.7 cm, relatively well-marginated left adrenal mass with central high signal intensity, suggesting an internal hemorrhage. (B) Gadolinium injection revealed heterogeneous enhancement on delayed phase. |

| Fig. 2Abdominal CT showed a 14×12×10 cm sized, heterogeneously enhancing tumor mass (A) and a hemorrhagic fluid collection around the left kidney (B). |

| Fig. 3(A) The tumor cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm were associated with necrotic and hemorrhagic tissue (H&E stain,×100). (B) We also noted neoplastic, pleomorphic cells with high nuclear grade (H&E stain,×400). The tumor cells had immunoreactivity for synaptophysin (C), CD56 (D), alpha-inhibin (E), and melan-A (F). |

References

1. Allolio B, Fassnacht M. Clinical review: Adrenocortical carcinoma: clinical update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006. 91:2027–2037.

2. Suyama K, Beppu T, Isiko T, Sugiyama S, Matsumoto K, Doi K, et al. Spontaneous rupture of adrenocortical carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2007. 194:77–78.

3. Liguori G, Trombetta C, Knez R, Bucci S, Bussani R, Belgrano E. Spontaneous rupture of adrenal carcinoma during the puerperal period. J Urol. 2003. 170:1941.

4. Leung LY, Leung WY, Chan KF, Fan TW, Chung KW, Chan CH. Ruptured adrenocortical carcinoma as a cause of paediatric acute abdomen. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002. 18:730–732.

5. Bussani R, Camilot D, Trombetta C, Silvestri F. Chance diagnosis of low stage non-metastasized adrenal cortical carcinoma in a young woman with retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Pathol Res Pract. 2003. 199:761–763.

6. Aubert S, Wacrenier A, Leroy X, Devos P, Carnaille B, Proye C, et al. Weiss system revisited: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 49 adrenocortical tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002. 26:1612–1619.

7. Fassnacht M, Johanssen S, Quinkler M, Bucsky P, Willenberg HS, Beuschlein F, et al. Limited prognostic value of the 2004 International Union Against Cancer staging classification for adrenocortical carcinoma: proposal for a Revised TNM Classification. Cancer. 2009. 115:243–250.

8. Sturgeon C, Kebebew E. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for malignancy. Surg Clin North Am. 2004. 84:755–774.

9. Fassnacht M, Kenn W, Allolio B. Adrenal tumors: how to establish malignancy? J Endocrinol Invest. 2004. 27:387–399.

10. Sumino Y, Tasaki Y, Satoh F, Mimata H, Nomura Y. Spontaneous rupture of adrenal pheochromocytoma. J Urol. 2002. 168:188–189.

11. Amano T, Takemae K, Niikura S, Kouno M, Amano M. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to spontaneous rupture of adrenal myelolipoma. Int J Urol. 1999. 6:585–588.

12. Denzinger S, Burger M, Hartmann A, Hofstaedter F, Wieland WF, Ganzer R. Spontaneous rupture of a benign giant adrenal adenoma. APMIS. 2007. 115:381–384.

13. Cerwenka H, Karaic R, Pfeifer J, Wolf G. Laceration of a benign adrenal adenoma mimicking a splenic rupture. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1998. 383:249–251.

14. Pommier RF, Brennan MF. An eleven-year experience with adrenocortical carcinoma. Surgery. 1992. 112:963–970.

15. Icard P, Louvel A, Chapuis Y. Survival rates and prognostic factors in adrenocortical carcinoma. World J Surg. 1992. 16:753–758.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download