Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to systematically review and analyze disasters involving South Korean hospitals from 1990 and to introduce a newly developed implement to manage patients' evacuation.

Materials and Methods

We searched for studies reporting disaster preparedness and hospital injuries in South Korean hospitals from 1990 to 2008, by using the Korean Studies Information Service System (KISS, copyright Korean Studies Information Co, Ltd, Seoul, Korea) and, simultaneously, hospital injuries which were reported and regarded as a disaster. Then, each study and injury were analyzed.

Results

Five studies (3 on prevention and structure, 1 on implement of new device, and 1 on basic supplement to current methods) and 8 injuries were found within this period. During the evacuations, the mean gait speed of walking patients was 0.82 m/s and the mean time of evacuation of individual patients was 38.39 seconds. Regarding structure evaluation, almost all hospitals had no balconies in patient rooms; hospital elevators were placed peripherally and were insufficient in number. As a new device, Savingsun (evacuation elevator) was introduced and had some merits as a fast and easy tool, regardless of patient status or the height of hospital.

Disasters and mass gatherings can lead to many injuries and great socioeconomic losses. If such events happen in important facilities, these losses can be greatly increased. Also, without significant disaster experience, many hospitals remain unprepared for natural disasters.1 During the last 20 years, Korea has experienced a number of disasters. In the mid-1990s, a bridge in Seoul collapsed, causing 32 deaths and plunging the city into confusion. In another case, a luxury department store in Seoul collapsed, causing 501 deaths. In 2003, a fire on a subway train killed 186 people. However, we consider that a hospital disaster would be much worse because of the number of disabled and non-movable patients and the difficulty of finding alternative treatment locations. Until now, reports of hospital disasters have been rare in Korea and have been associated with architectural deficiencies and mechanical and instrumental failures. Recently, a detailed study of "Savingsun," a device used to escape from high buildings, has been reported.2,3 This implement is able to attach to the wall of the building and will safely slide down with non-moter rubber wheel after the total body of this is pulled out during disaster situation (Fig. 1).

In this paper, we report on hospital disasters in Korea, both those that have and those that have not been reported in prior studies, and compare with other rescue devices. We also introduce a newly developed device for use in hospital disasters.

We collected studies published about hospital disasters in Korea from 1990 to 2008 through the Korean Studies Information Service System (KISS, copyright Korean Studies Information Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea).4 We used the keywords "hospital", "disaster", "fire", "instrument", and "escape" to search the KISS. Then, we searched for the corresponding author, the specialty of the lead author, the discipline represented in the study (architecture, medicine, prevention, and equipment), the study period, the publishing institution, and the results of each study. Also, searching with 3 representative internet sites (naver.com, google.co.kr, and daum. com) of South Korea, we identified accidents that had not been reported over the same period, and we analyzed these accidents according to the year of occurrence, the hospital size, and the number of injuries. We compared them with various checklists; capacity, height, application, limitation, operation, emotion, safety, and economy. The analysis was performed using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and Fisher's exact test was used to measure differences between variables.

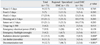

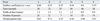

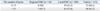

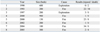

We found a total of five studies listed in KISS (Table 1). The specialty of the lead author was fire in three cases, architecture in one, and medicine in one. The field of study represented was equipment in one case, prevention in three, and emergency provisions in one. The average duration of these studies was 1.2 years. Across all studies, the mean walking speed of patients during escape was 0.82 m/s, which was a little slower than normal adult walking speed (1.2 m/s). The mean time for escape for patients who could walk was 38.39 ± 30.33 seconds. The lack of balconies was one of the greatest hindrances to escape because traditional building escape ways have been introduced two escape routes: by way of the balcony or through a hallway. Also, the elevators were located at the ends of the hallway and were few in number. The outflow coefficient [The formula of outflow coefficient = person/(width of door×time)/(m×sec)] was measured for real and ideal escape time evaluation in 6 wards. 1.3-1.6 person/(m×sec) was normal but, in this study, the mean was 0.47 person/(m×sec) and each result had difference with normal patient ratio. This formula was introduced as an effective tool to calculate the escape number of persons with considering all factors in the ward (Table 2). In terms of emergency provisions, as recorded for 71 in 118 emergency medical centers, less than one-quarter had sufficient reserve water (12.7%), food (7%), fluids (23.9%), dressings (21.1%), and sutures (21.1%) to last for 3 days. Even fewer had sufficient emergency flashlights (4.2%), emergency blankets (16.9%), and portable oxygen tanks (4.2%) available for use during a disaster. Sixty-six emergency departments (93%) had emergency electrical power, but only seven (9.9%) had independently powered equipment. A very small number of emergency departments had radiation detectors (15.5%), air raid shelters (11.3%), or decontamination tents (12.7%); regional and specialized emergency medical centers were much more likely to have such supplies available than local emergency centers (p = 0.008, 0.009, < 0.001, respectively) (Table 3). A total of 118 emergency medical centers were evaluated for height, and 30.2% of these were located in buildings over 15 stories high (Table 4). A comparison of Savingsun and other rescue devices (Descending lifeline, Air cushion, Sliding mate) showed that the descending life line was the cheapest device and Savingsun the most expensive (about 10,000 USD). In terms of capacity, Savingsun was limited to 15 individuals, whereas the Air cushion and the Sliding mate had unlimited capacity; however, Savingsun could be deployed for all kinds of patients and had a rapid rescue time (within 30 seconds) (Table 5).

We found eight studies on hospital disasters, two in university hospitals and six in local hospitals. The disasters were caused by explosions in three cases and fires in five (Table 6). A total of 136 injuries and 48 deaths were reported; deaths included 23 patients, 11 employees, 10 relatives of patients, and four people unrelated to the hospital.

Korea has experienced relatively few natural disasters compared with neighboring countries.5 However, the current national disaster system was created in the wake of some major accidents and international events. The emergency medical system was established for the Asian Games in 1986 and the Seoul Olympic Games in 1988. The collapse of Seong-soo Bridge was the basis for the development of laws regarding emergency medical training, and the collapse of Sampoong Department Store led to the creation of the field of emergency medicine. Recently, an emergency medical fund was created after the Daegu Subway explosion, which made possible the current emergency medical system. These disasters were the result of structural defects.

In Korea, hospitals are mostly tall buildings, built without due regard to disasters; therefore, if a disaster were to happen, the number of injuries and deaths could be high. Also, the methods of escape and rescue from hospitals in any disaster would be very limited.6 In particular, few studies have examined escape routes, structural aspects of disaster prevention, disaster control personnel, and rescue equipment.7 Until now, the escape and rescue routes in most hospitals consist of a few elevators or narrow staircases, and rescue equipment has only been available for ambulatory patients.8 However, studies on the preparedness of the medical disaster system for biological or radiological disasters have rapidly developed due to the increased threat of these kinds of major disasters.9-14 The American Red Cross and the Federal Emergency Management Agency have recommended that provisions should be made for sufficient food and water for 72 hours in the event of a disaster.15,16 If a hospital disaster occurred in Korea at present, major problems would arise because only nine emergency medical centers have sufficient food, and only five have sufficient water.17 Currently, the emergency medical system of hospitals have been made with 4 division; regional, specialized, local and other facilities. But there was no facility just for disaster. Therefore, the preparedness and policy of disaster could be made in this system.

Among Asian nations, Japan has the best-prepared disaster prevention system in terms of architecture, equipment, and emergency medical systems because it has often been subject to natural disasters such as typhoons and earthquakes. However, Japan also did not fulfill the criteria for adequate disaster preparedness based on the categories queried in almost hospital unilt mid of 1990s.18 A lot of research and policies have been changed and could be a representative country in disaster preparedness of the world. In Japan, a hospital dedicated solely to disasters can supply rapidly medical teams and provide sufficient rescue materials. In particular, a disaster simulation educational center has been established to provide direct or indirect experience and knowledge to people of all ages from kindergarten on. Also, the Disaster Medical Assistance Team (DMAT), Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) have played important roles in real-life domestic and international disasters.19,20

The United States (US) is known worldwide for its disaster management. The US originated the detailed systems that have been known until now, and it has also developed more specialized disaster responses based on many actual disaster experiences within the country. In particular, the role of hospitals in the community response to disasters has received increased attention, especially since the terro-rist attacks of September 11, 2001.21 However, almost all hospitals in the US are relatively low structures compared with those in Korea; therefore, few studies have examined disaster management in very high multi-story hospitals. In 2005, hurricane Katrina was regarded as an important disaster due in part to the disruption of hospital infrastructure, and many reports have suggested that a more effective response and prevention program must be implemented.22-26

The speed of patients' escape was certainly slower than normal walking speed, and the mean time for escaping from a ward was 38 seconds (maximum, > 200 seconds). This delay resulted from the physical bottlenecks in hospitals, and greater levels of training and better facilities are required, as this situation may be more severe in a real-life disaster. Savingsun was made in Korea in 2005 and was registered at the Korean intellectual property office. The report in literature was latest compared with other devices and, from the results of study, this may be the best equipment for rescue from higher multi-story hospitals in term of time and capacity and because it is not dependent on the physical condition of the patients and does not require electrical power.2 However, it is expensive and not reported widely to other countries except of Asia. Realistic disaster drills proved to be the most effective technique for enhancing preparedness in Korea because actual hospital disasters rarely occur.27-29

In conclusion, hospital disasters must be prevented because they would cause relatively more physical and psychiatric problems and complications than would other disasters.

To prevent such disasters, more effective equipment such as Savingsun should be placed in all hospitals, and more detailed training programs and studies should be established at all kinds of hospitals in Korea.

Figures and Tables

Table 3

Comparison of Disaster Preparedness between Regional or Specialized and Local Emergency Medical Center (EMC): Presence of Supplies and Equipments6 (n (%))

References

1. Barbera JA, Yeatts DJ, Macintyre AG. Challenge of hospital emergency preparedness: analysis and recommendations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009. 3:S74–S82.

2. Lee YJ, Yoon MO, Park JS, Lee DH. A study on the life saving implement of high-rise building. T. of Korean Institute of Fire Sci. & Eng. 2005. 365–371. (C-16).

3. Accessed February 7, 2010. Available at: http://119savingsun.com/.

4. Accessed February 7, 2010. Available at: http://kiss.kstudy.com/.

5. Disaster response system. National Emergency Medical Center. Accessed september 11, 2007. available at: http://www.nemc.go.kr/.

6. Kim ES, Lee JS, Park SM, You HK. A study on evacuation of patients in hospitals: part II. T. of Korean Institute of Fire Sci & Eng. 2005. 19:28–36.

7. Kim ES, Lee JS, Kim MH, You HK, Song YH, Min KC. A study on evacuation of patients in hospitals: part I. T. of Korean Institute of Fire Sci. & Eng. 2005. 19:20–28.

8. Yim JH, Kim HJ, Kim E, Park HS, Choi J. A study on the fire protection plan of hospital building through case studies. T. of Korean Institute of Fire Sci. & Eng. 2005. 199–204. (C-01).

9. Park TJ, Kim WJ, Yun JC, Oh BJ, Lim KS, Lee BS, et al. Emergency medical centers preparedness for a biological disaster in Korea. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2008. 19:263–272.

10. Baker DJ. The pre-hospital management of injury following mass toxic release; a comparison of military and civil approaches. Resuscitation. 1999. 42:155–159.

11. Srivatsa LP. The Bhopal tragedy. J Toxicol Clin Exp. 1987. 7:47–49.

12. Okumura T, Suzuki K, Fukuda A, Kohama A, Takasu N, Ishimatsu S, et al. The Tokyo subway sarin attack: disaster management, Part I: Community emergency response. Acad Emerg Med. 1998. 5:613–617.

13. Greenberg MI, Hendrickson RG. CIMERC. Drexel University Department Terrorism Preparedness Consensus Panel. Report of the CIMERC/Drexel university emergency department terrorism preparedness consensus panel. Acad Emerg Med. 2003. 10:783–788.

14. Kim DO, Oh BJ, Hong ES, Lee JH, Kim W, Ahn JY, et al. Surveillance on hazardous material preparedness in the emergency deparment in Korea: personal protection equipment. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2007. 18:48–55.

15. Preparedness kit features recommended items ofr emergencies. American Red Cross. Accessed September 11, 2007. available at: http://www.redcorss.org/.

16. Basic disaster supplies. Federal Emergency Management Agency. Accessed September 11, 2007. available at: http://www.fema.gov/.

17. Sohn CH, Yoon JC, Oh BJ, Kim W, Lim KS. Hospital disaster preparedness in Korea: aspect of basic sypplies during a disaster. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2008. 19:22–30.

18. Kai T, Ukai T, Ohta M, Pretto E. Hospital disaster preparedness in Osaka, Japan. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1994. 9:29–34.

19. Accessed February 7, 2010. Available at: http://www.jica.go.jp/.

20. Accessed February 7, 2010. Available at: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/.

21. Sauer LM, McCarthy ML, Knebel A, Brewster P. Major influences on hospital emergency management and disaster preparedness. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009. 3:S68–S73.

22. Gray BH, Hebert K. Hospitals in Hurricane Katrina: challenges facing custodial institutions in a disaster. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007. 18:283–298.

23. Sanders CV. Hurricane Katrina and the LSU-New Orleans Department of Medicine: impact and lessons learned. Am J Med Sci. 2006. 332:283–288.

24. Sariego J. A year after hurricane katrina: lessons learned at one coastal trauma center. Arch Surg. 2007. 142:203–205.

25. Braun BI, Wineman NV, Finn NL, Barbera JA, Schmaltz SP, Loeb JM. Integrating hospitals into community emergency preparedness planning. Ann Intern Med. 2006. 144:799–811.

26. LaCombe DM. 72 hours: what rescuers can anticipate before help arrives. JEMS. 2005. 30:75–79.

27. Ferrer RR, Ramirez M, Sauser K, Iverson E, Upperman JS. Emergency drills and exercises in healthcare organizations: assessment of pediatric population involvement using after-action reports. Am J Disaster Med. 2009. 4:23–32.

28. Timm N, Kennebeck S. Impact of disaster drills on patient flow in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2008. 15:544–548.

29. Kaji AH, Langford V, Lewis RJ. Assessing hospital disaster preparedness: a comparison of an on-site survey, directly observed drill performance, and video analysis of teamwork. Ann Emerg Med. 2008. 52:195–201. 201.e1–201.e12.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download