Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to investigate peculiar patterns of facial asymmetry following incomplete recovery from facial paralysis that require optimal physical therapy for effective facial rehabilitation, and to decrease the incidence of avoidable facial sequelae.

Materials and Methods

This study involved 41 patients who had facial sequelae following the treatment of various facial nerve diseases from March 2000 to March 2007. All patients with a follow-up of at least 1 year after the onset of facial paralysis or hyperactive function of the facial nerve were evaluated with the global and regional House-Brackmann (HB) grading systems. The mean global HB scores and regional HB scores with standard deviations were calculated. Other factors were also analyzed.

Results

Four patterns of facial asymmetry can be observed in patients with incomplete facial recovery. The most frequently deteriorated facial movement is frontal wrinkling, followed by an open mouth, smile, or lip pucker in patients with sequelae following facial nerve injury. The most common type of synkinesis was unintended eye closure with an effort to smile.

The facial nerve can be damaged in various manners: viral infection, trauma, surgery for inflammation or cancer, and idiopathic neuropathy. Unexpected sequelae as a consequence of incomplete recovery after facial nerve injury poses a grave social and emotional challenge to the health of patients, even when the sequelae are not caused by life-threatening pathology. In some patients, psychological distress may become an even more significant problem than the functional losses.

The main location of injury along the course of the facial nerve is largely dependent on the cause of injury; however, the topognostic features of facial asymmetry are known to not always be related to the cause or site of injury.

Given this, what causes the partial sequelae of facial mimetic muscles in some patients with facial paralysis? Recovery of some part of the facial muscle is either incomplete or non-existent.1 There does not appear to be a risk following neuropraxia. The unusual behavior of several facial muscles is not yet explained.

Whatever the cause of nerve damage, whatever the site of facial nerve, and whatever the grade of facial paralysis, we studied peculiar patterns of facial asymmetry following incomplete recovery from facial nerve injury using the regional House-Brackmann (HB) facial nerve grading system2 and the global HB facial nerve grading system, in an effort to better understand unexplained special features of mimetic muscles that have different restorations of each other. These systems were used to enhance the description of the partial defect of facial function, and to develop an optimal strategy of physical therapy as a final treatment option for effective facial recovery and for decreasing the incidence of avoidable sequelae.

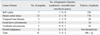

Patients who had facial nerve damage between March 1990 and March 2007 were collected for evaluation of facial sequelae between June 2007 and June 2008. 41 patients had facial function sequelae following treatment of various facial nerve diseases (Table 1).

Facial function was directly evaluated by two experienced physicians from the Department of Otorhinolarynglogy at the Yonsei University College of Medicine at least 1 year after the onset of facial paralysis (the mean follow-up period: 4.3 ± 1.8 years). The HB grading scale with regional and global scores was used.

Preoperative dysfunction in the 31 patients who underwent surgical treatment was graded using the global HB grading scale only.

Using regional scores based on the HB scale, facial nerve function was evaluated for the forehead (F), eyes (E), nose (N), and mouth (M). Synkinesis was also evaluated as absent (A) and present (P). Evaluation of facial function using the global and regional HB grading systems was carried out simultaneously.

In order to inspect any peculiar feature of facial movement or asymmetry, we attempted to identify common patterns of facial asymmetry and to describe types of facial sequelae depending on the anatomical distribution of facial nerve branches accompanied by hyperactive function of the facial nerve. The mean global HB scores and the mean regional HB scores were calculated with standard deviations to investigate frequently deteriorated facial movements.

Many factors are taken into consideration in the data collection, including age, sex, side of involvement, initial grading scores, and cause of the lesion.

The ages of the 41 patients ranged from 16 to 82 years (mean: 46 years). Gender (20 male and 21 female patients) and side involvement (18 right and 23 left) were nearly equally distributed. Thirteen patients underwent facial nerve decompression for severe facial paralysis [defined as greater than 90% denervation on electroneurography (ENoG) within 3 weeks of onset and total denervation potential on electromyography (EMG)] via a middle fossa approach or a transmastoid approach within three weeks of the onset of facial paralysis. Six patients underwent facial nerve grafts with the sural nerve or the great auricular nerve immediately following radical parotidectomy for malignancy. Seven patients underwent surgery for facial nerve schwannomas using a function preservation technique proven by postoperative evaluation. Five patients underwent surgery for vestibular schwannomas via a translabyrinthine approach or an infratemporal fossa approach type A with preservation of the facial nerve. Ten patients were treated with prednisolone for 10 days (60 mg a day for the first 5 days, tapered thereafter) plus acyclovir (1,500 mg a day) for 5 days for incomplete facial paralysis caused by Bell's palsy or herpes zoster oticus. All surgical procedures were performed by the senior author (WS Lee).

The information of patients with facial sequelae is presented in Table 2. There were four common patterns of facial asymmetry, depending on the anatomical distribution of facial nerve branches.

The most common configuration of facial asymmetry includes obvious weakness of the forehead with symmetry at rest, mild weakness of eye closure, slight weakness in midface movement, obvious weakness of movement of the corner of the mouth, disfiguring asymmetry with motion, and symmetry at rest (Fig. 1A) (n = 22/41, F ≥ M ≥ E, N).

The second type of facial asymmetry includes obvious weakness of the forehead with symmetry at rest, mild weakness of eye closure, slight weakness in midface movement, slight weakness of movement of the corner of the mouth, disfiguring asymmetry with motion, and symmetry at rest (Fig. 1B) (n = 8/41, F > E, N, M).

The third type of facial asymmetry includes slight weakness of the forehead with symmetry at rest, mild weakness of eye closure, normal midface movement, obvious weakness of movement of the corner of the mouth, disfiguring asymmetry with motion, and symmetry at rest (Fig. 1C) (n = 8/41, E, M > F, N).

The fourth type of facial asymmetry includes slight weakness of the forehead with symmetry at rest, mild weakness of eye closure, normal or slight weakness of midface movement, slight weakness of movement of the corner of the mouth, disfiguring asymmetry with motion, and symmetry at rest (Fig. 1D) (n = 3/41, F≈E≈N≈M).

The mean initial HB grading score was 3.58 ± 1.44 and the final HB grading score for facial asymmetry was 2.29 ± 0.53. The mean regional HB grading score was 3.38 ± 0.96 for the forehead, 1.86 ± 0.48 for the eyelid, 1.80 ± 0.59 for the midface, and 2.65 ± 0.58 for the mouth.

The most frequently deteriorated facial movement was frontal wrinkling, followed by an open mouth, smile, or lip pucker in patients with sequelae following facial nerve injury.

Hyperactive function of the facial nerve was seen in 13 patients. Synkinesis (n = 4, unintended eye closure with an effort to smile or blow, n = 1, unintended movement of the philtrum with an effort to close the eye), crocodile tears (n = 6), and hemifacial spasm (n = 2) were found to be facial sequelae that could potentially cause distress to patients.

Incomplete recovery of the facial motor system following facial nerve injury can be an obstacle for multiple human functions critical for physical, social, and psychological well-being.3,4 Different degrees of distortion and/or recovery of individual nerve branches or individual musculature following nerve injury have made it difficult to understand the facial motor system. With no evidence of topognostic features, functional facial movements or expressions are a result of a combination of facial muscle contractions and not the outcome of a single isolated muscle contraction.5 Little is known regarding why different degrees of distortion of individual branches can be induced following facial nerve injury.

However, little is known regarding the peculiar patterns of facial sequelae following nerve deterioration. A better understanding of these patterns is critical in order to provide patients with a chance for complete recovery of facial movement. Therefore, rehabilitation for facial paralysis or facial movement dysfunction after insult to the facial neuromotor system has previously been expected to provide little benefit. Sporadic evidence shows benefits of neuromuscular reeducation; however, no randomized trials have examined if, when, or what type of physical therapy regimen provides an optimal benefit to patients suffering from acute facial paralysis. Thus, the availability of facial rehabilitation is limited, and most individuals with facial movement disorders have been instructed to wait for spontaneous recovery or told that no effective intervention exists.6,7

A recently emerging rehabilitation science called neuromuscular reeducation is gaining support as a means to provide patients with disorders of facial control an opportunity to recover facial movement and function.8-10 Neuromuscular reeducation is a process that facilitates the return of intended facial movement patterns and eliminates unwanted patterns of facial movement and expression.

Unresolved facial sequelae and synkinesis, which can occur during recovery from facial nerve injury despite steroid and/or antiviral treatment and even surgical intervention, can be cured with facial neuromuscular reeducation concentrating on the most frequently deteriorated facial movements.

However, facial rehabilitation has not been widely available in the past because it was not considered to provide significant benefits to patients.

Is it helpful to conduct physical therapy concentrated on the most frequently deteriorated facial movements, such as frontal wrinkling, an open mouth, smiling, or lip puckering? Can physical therapy work to avoid synchronous movement of the ipsilateral periocular and perioral muscles?

VanSwearingen, et al.11 demonstrated a pattern of reductions in synkinesis and increases in intended facial movement after neuromuscular reeducation in physical therapy.

In our experience, following an insult to the facial nerve, recovery of the frontalis muscle is either incomplete or non-existent. In our study, frontal wrinkling was observed to be a facial movement that was easily distorted by changes in the resting facial posture or voluntary movement. The frontalis muscle is a thin, bilateral, quadrilateral muscle intimately adhered to the superficial fascia. This muscle is innervated by the facial nerve, and inserts deeply into the skin.12

It is reasonable to think that the frontalis muscle is susceptible to atrophy and fibrosis. Histologic examination of this muscle after varying periods of denervation may lend support to this idea.13

Hyperactive function of the facial nerve was seen in 13 patients. Synkinesis more frequently occurred in herpes zoster oticus than in Bell's palsy. This phenomenon is thought to be due to virulent characterisctics of the varicella zoster virus.14

Crocodile tears and hemifacial spasms were found to be facial sequelae that could potentially cause distress to patients. In conclusion, we described common configurations of facial asymmetry seen in incomplete recovery following facial nerve injury in an attempt to develop an optimal strategy for physical therapy for complete and effective facial recovery, and to decrease the incidence of avoidable sequelae.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Lundborg G. Nerve Injury and Repair. 2004. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

2. Yen TL, Driscoll CL, Lalwani AK. Significance of House-Brackmann facial nerve grading global score in the setting of differential facial nerve function. Otol Neurotol. 2003. 24:118–122.

3. Neely JG, Neufeld PS. Defining functional limitation, disability, and societal limitations in patients with facial paresis: initial pilot questionnaire. Am J Otol. 1996. 17:340–342.

4. Twerski A, Twerski B. May M, editor. The emotional impact of facial paralysis. The facial nerve. 1986. New York, NY: Thieme;788–794.

5. Schmidt KL, VanSwearingen JM, Levenstein RM. Speed, amplitude, and asymmetry of lip movement in voluntary puckering and blowing expressions: implications for facial assessment. Motor Control. 2005. 9:270–280.

6. Bateman DE. Facial palsy. Br J Hosp Med. 1992. 47:430–431.

7. Ohye RG, Altenberger EA. Bell's palsy. Am Fam Physician. 1989. 40:159–166.

8. Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM, Lenert J, Johnson PC. Facial neuromuscular retraining for oral synkinesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997. 99:1922–1931.

9. Deleyiannis FW, Askari M, Schmidt KL, Henkelmann TC, VanSwearingen JM, Manders EK. Muscle activity in the partially paralyzed face after placement of a fascial sling: a prelliminary report. Ann Plast Surg. 2005. 55:449–455.

10. Manikandan N. Effect of facial neuromuscular re-education on facial symmetry in patients with Bell's palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2007. 21:338–343.

11. VanSwearingen JM, Brach JS. Changes in facial movement and synkinesis with facial neuromuscular reeducation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003. 111:2370–2375.

12. Spiegel JH, Goerig RC, Lufler RS, Hoagland TM. Frontalis midline dehiscence: an anatomical study and discussion of clinical relevance. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009. 62:950–954.

13. Miehlke A, Fisch Ugo, Eneroth CM. Surgery of the facial nerve. 1973. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg.

14. Meier JL, Straus SE. Comparative biology of latent varicellazoster virus and herpes simplex virus infections. J Infect Dis. 1992. 166:S13–S23.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download