Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to investigate how clinical features such as sex, age, etiologic factors, and presenting symptoms of odontogenic sinusitis are differentiated from other types of sinusitis. Also, this study was designed to find methods for reducing the incidence of odontogenic sinusitis.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective chart analysis was completed on twenty-seven patients with odontogenic sinusitis. They were all treated at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital between February 2006 and August 2008. The study protocol and informed consent forms were approved by the institutional review boards for human beings at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital.

Results

Ten patients (37.0%) had dental implant related complications and 8 (29.6%) had dental extraction related complications. Unilateral purulent nasal discharge was the most common symptom (66.7%). The therapeutic modality included transnasal endoscopic sinus surgery in 19 (70.4%) patients, and a Caldwell-Luc operation in two (7.4%) patients.

Conclusion

In our study, there was no significant difference in the incidence between genders. The average age of the patients was 42.9 years. The incidence was highest in the fourth decade. There were no significant differences between the symptoms of odontogenic sinusitis and that of other types of sinusitis. However, almost all of the patients with odontogenic sinusitis had unilateral symptoms. Iatrogenic causes, which include dental implants and dental extractions, were the most common etiologic factors related to the development of odontogenic sinusitis. Therefore, a preoperative consultation between a rhinologist and a dentist prior to the dental procedure should be able to reduce the incidence of odontogenic sinusitis.

The origin of sinusitis is considered to be primarily rhinogenous.1 In some cases, a dental infection is a major predisposing factor.1 Sinusitis with an odontogenic source accounts for 10% of all cases of maxillary sinusitis.1,2 Although odontogenic sinusitis is a relatively common condition, its pathogenesis is not clearly understood and there is lack of consensus concerning its clinical features, treatment, and prevention. Odontogenic sinusitis deserves special consideration because it differs in microbiology, pathophysiology, and management compared to sinus diseases with other origins.2 Previous studies have reported that the incidence is higher in women,2 and Kaneko reported that younger individuals (third and fourth decade) appear to be more susceptible.2 Odontogenic sinusitis occurs when the Schneidarian membrane is perforated.3 This can happen in people with maxillary teeth caries and maxillary dental trauma. There are also iatrogenic causes, such as the placement of dental implants and dental extractions.3 The treatment of odontogenic sinusitis often requires management of the sinusitis as well as the odontogenic origin.3

We carried out a retrospective study of 27 patients who had various causes of odontogenic sinusitis to determine the clinical features, such as sex, age, etiologic factors, presenting symptoms, therapeutic tools, and radiological findings. We were looking to find the most appropriate diagnostic methods. During this study we attempted to measure the ratio of iatrogenic causes such as implants (which have an increased incidence recently), and to think about how these problems could be solved.

We examined the 30 patients who were given a diagnosis of odontogenic sinusitis in our Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery from February 2006 through August 2008. Three cases of pansinusitis with nasal polyps were excluded from this study. Twenty-three of the 27 patients were initially diagnosed in our department (85.2%). Four patients were referred from a dentist's office (14.8%). The diagnosis of odontogenic sinusitis is based on a thorough dental and medical examination. This includes an evaluation of the patient's symptoms (according to the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) criteria, a diagnosis of rhinosinusitis requires at least 2 major factors or at least 1 major and 2 minor factors from a series of clinical symptoms and signs), a past dental history, and radiological findings, including a paranasal sinus CT scan. In addition, consultation with the dentistry department supported us in making a diagnosis of odontogenic sinusitis.

The patients were retrospectively analyzed according to medical records, which includes sex, age, presenting symptom, etiologic factors, surgical and medical treatment, cultures, and radiological results which includes involved sinus and teeth.

In our study, the male to female ratio was 15 : 12, with a higher incidence in men. The age distribution was 4 to 75 years, with an average age of 42.9 years. The incidence was highest in the fourth decade. All patients have no previous history of sinusitis. The follow-up period was between 2 months and 6 months, with an average of 4.5 months.

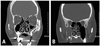

In this study, odontogenic sinusitis accounts for about 5.2% of all maxillary sinusitis cases. Several conditions of odontogenic sinusitis were found. Dental implant-related complications were the most common cause, found in 10 (37%) of the 27 patients (Fig. 1A). Dental extraction-related complications were the second most common cause, found in 8 (29.6%) of the 27 patients. A dentigenous cyst was seen in 3 (11.1%) patients. A radicular cyst, dental caries, and a supernumenary tooth were the least common causes, with each found in 2 (7.4%) of the 27 patients (Fig. 2).

The interval from the dental procedures to the first visit to the outpatient clinic with symptoms was 1 month in 11 (40.8%), 1 to 3 months in 5 (18.5%), 3 months to 1 year in 8 (29.6%), and over a year in 3 cases (11.1%).

23 patients out of a total of 27 had been diagnosed directly after admission to otorhinolaryngology without dental treatment. Only four patients were diagnosed with odontogenic sinusitis via a post dental treatment consultation. 25 of 27 patients did not have a preoperative consultation between a rhinologist and a dentist prior to the dental procedure. A preoperative consultation between a rhinologist and a dentist prior to a dental procedure should be able to reduce the risk of developing odontogenic sinusitis.

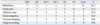

The most common presenting symptom was unilateral purulent rhinorrhea. This rhinorrhea was found in 18 patients (66.7%). This was followed by cheek pain in 9 (33.3%) patients, an offensive odor in 7 patients (25.9%), unilateral nasal congestion in 5 patients (18.5%), postnasal dripping in 4 patients (14.8%), and upper gingiva swelling and discharge in 4 patients (14.8%). No patient complained of having a febrile symptom. One patient (3.7%) without symptoms was diagnosed incidentally by radiography (Table 1). There were no significant differences between the symptoms of odontogenic sinusitis and that of other types of sinusitis. However, almost all of the patients with odontogenic sinusitis had unilateral symptoms.

A paranasal sinus CT was carried out in all cases. Bony erosion of the involved maxillary sinus was observed in 12 cases (44.4%). An oroantral fistula was observed in 7 cases (25.9%) (Fig. 1B). The distribution of paranasal sinuses showing a soft tissue density is as follows: the maxillary sinus in 19 cases (70.4%), the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses in 5 cases (18.5%), the maxillary, ethmoid, and frontal sinuses in 2 cases (7.4%), and the maxillary, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses in 1 case (3.7%). There were no cases in which all paranasal sinuses showed a soft tissue density.

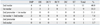

The distribution of involved teeth in the upper jaw was as follows: the 2nd molar in 11 cases (40.8%), the 1st molar in 9 cases (33.3%), the 2nd premolar and 1st molar in 3 cases (11.1%); the 1st molar and 2nd molar in 2 cases (7.4%), the 2nd premolar in 1 case (3.7%), and the 3rd molar in 1 case (3.7%) (Table 2).

In 14 patients out of a total of 27, intraoperative bacterial cultures were obtained. Aerobic organisms alone were recovered in 3 cases (21.4%), anaerobes only were isolated recovered in 1 (7.1%), and mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were recovered in 3 (21.4%). The predominant aerobes were S. aureus. The predominant anaerobes were anaerobic gram-negative bacilli and Peptostreptococcus spp. No correlation was found between the predisposing odontogenic conditions and the microbiological findings.

The therapeutic modalities included transnasal endoscopic sinus surgery in 19 cases (70.4%), a Caldwell-Luc operation in 2 cases (7.4%), 2 cases (7.4%) of dental management including dental extractions and dental implant removal, and 4 cases (14.8%) involving only antibiotic treatment (Table 3). The cases for a Caldwell-Luc operation were obvious as they provided maximal exposure for the removal of a large radicular cyst and a supernummenary tooth that was located laterally in the sinus, making the endoscopic approach impossible. No recurrences were observed during the follow-up period for all patients. Six patients who declined surgical treatment were treated only with antibiotics. Antibiotics (cefditoren pivoxil 300 mg/day or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 1,875 mg/day) were used routinely for 3 weeks after the surgery. The follow-up period was between 2 months and 6 months, with an average of 4.5 months.

There were 10 cases with dental implant-related complications. These included six males and four females with an average age of 52.3 years (range: 35-62 years). The interval from the dental implant procedures to the first visit to the outpatient clinic with symptoms was 1 month in 6 (60%), 1 to 3 months in 2 (20%), 3 months to 1 year in 1 (10%), and over a year in 1 case (10%).

Seven patients suffered from unilateral purulent rhinorrhea. There was cheek pain and an offensive odor in four cases (Table 1). The most commonly involved tooth was the second molar in the upper jaw (4 cases) (Table 2). Therapeutic modalities included transnasal endoscopic sinus surgery in nine cases and dental management, including dental extractions and dental implant removal, in one case (Table 3).

There were eight cases with dental extraction-related complications. These included four males and four females with an average age of 39.3 years (range: 22-61 years). Five patients suffered from unilateral purulent rhinorrhea. There was cheek pain and an offensive odor in 3 cases (Table 1). The most commonly involved tooth was the second molar in the upper jaw (4 cases) (Table 2). Therapeutic modalities included transnasal endoscopic sinus surgery in seven cases and antibiotic treatment in one case (Table 3).

Previous studies have reported that the incidence is higher in women,2 but in our study the male to female ratio was 1.25 : 1. There was no significant difference in the incidence between sexes. Kaneko reported that younger individuals (third and fourth decade) appear to be more susceptible.4 In the present study, the average age of the patients was 42.9 years. The incidence was highest in the fourth decade.

The incidence of sinusitis associated with odontogenic infections is very low despite the high frequency of dental infections.5 However, this incidence is gradually increasing. In our study, the most common cause (10 cases) was dental implant-related complications.

In our study, 18 (66.7%) of the 27 patients complained of unilateral purulent rhinorrhea as the main symptom. There were no significant differences between the symptoms of odontogenic sinusitis and that of other types of sinusitis (AAO-HNS criteria for rhinosinusitis). In this study, we could not diagnose odontogenic sinusitis based only on the presenting symptoms. However, almost all of the patients with odontogenic sinusitis had unilateral symptoms. The possibility of odontogenic sinusitis should always be considered when a patient has unilateral symptoms. The appropriate work-up includes a history of dental treatment, radiological examination, and dental examinations.

The 2nd molar roots are the closest to the maxillary sinus floor, followed by the roots of the 1st molar, 2nd premolar, and 1st premolar.6,7 These short distances explain the easy extension of an infectious process from these teeth to the maxillary sinus. In our cases, the 2nd molar (40.8%) in the upper jaw was the most common source. The diagnosis of odontogenic sinusitis is based on conducting an appropriate examination that included an evaluation of current symptoms and a medical history. This history is correlated with the physical findings. Radiological imaging is an important tool for establishing the diagnosis. A CT is an excellent tool for diagnosing odontogenic sinusitis. A CT can show the relationship of the odontogenic origin to the maxillary sinus floor defect and the diseased tissues. It can also determine the exact location of a foreign body within the maxillary sinus.8,9

Concomitant management of the dental origin and the associated sinusitis will ensure complete resolution of the infection and may prevent recurrence and complications. A combination of medical and surgical approaches is generally required for the treatment of odontogenic sinusitis. The source of the infection must be eliminated in order to prevent a recurrence of sinusitis. The removal of a foreign tooth root from the sinus, or the treatment of an infected tooth by extraction or root canal therapy, was required to eliminate the source of infection. Dental infections are usually mixed polymicrobial aerobic and anaerobic bacterial infections caused by the same families of oral microorganisms made of obligate anaerobes and gram positive aerobes.6 Oral administration of antibiotics are effective against oral flora and sinus pathogens for 21 to 28 days.2 More recently, less invasive transnasal endoscopic sinus surgery has been advocated for the treatment of odontogenic sinusitis. In our study, 70.4% of the patients underwent transnasal endoscopic sinus surgery, and 7.4% of the patients were managed with a Caldwell-Luc operation. In this case, the indication of a Caldwell-Luc operation was obvious as it provided maximal exposure for the removal of a large radicular cyst and a supernummenary tooth that was located laterally in the sinus, making the endoscopic approach impossible. Six patients who declined surgical treatment were treated only with antibiotics. No recurrences were observed during the follow-up period for these patients. After rhinologic surgical treatment, proper antibiotic therapy and dental treatments (removal of dental implants or dental caries, closure of oroantral fistula) for the odontogenic origin have been performed by dentist on all of the patients.

The most common cause of odontogenic sinusitis in this study was dental implant-related complications. It is known that the incidence of sinusitis associated with dental implants is very low despite the high frequency of dental implants. However, this incidence is gradually increasing. The most frequent adverse effect is local infection of the tissues around the dental implants. This may be associated with resorption of the surrounding bone. For this reason, dental implants placed very close to the maxillary sinus may offer a route for infection from the oral cavity to the sinus. The migration of a dental implant into the maxillary sinus may be another cause of maxillary sinusitis. This acts as a foreign body and produces chronic infection.10-12 The reasons dental implants migrate are unknown. It is likely that the scanty thickness of the maxillary sinus floor and edentulous induce inadequate implant anchorage and lead to a lack of primary stability.13 However, this may be simply a technical issue related to inadequate preparation or placement of the implant.14,15 Implants related to odontogenic sinusitis have a significantly higher incidence in patients who have predisposing factors, such as a thin maxillary sinus floor.4,16 We recommend preoperative evaluations for patients who suffer from previous symptoms of sinusitis or have predisposing factors in order to rule out structural drainage problems of the paranasal sinuses by intranasal observation and radiological examination. This could help identify patients with an increased risk of developing odontogenic sinusitis.

In conclusion, there was no significant difference in the incidence between male and female. The mean age of the patients was 42.9 years. The incidence was highest in the fourth decade. There were no significant differences between the symptoms of odontogenic sinusitis and that of other types of sinusitis. However, most of the patients with odontogenic sinusitis had unilateral symptoms. The possibility of odontogenic sinusitis should always be considered when a patient has unilateral nasal symptoms. A consultation between a rhinologist and a dentist before a dental procedure takes place in order to identify patients who have risk factors for odontogenic sinusitis should be able to prevent the development of odontogenic sinusitis, because the most common cause of odontogenic sinusitis is iatrogenic.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Paranasal sinus computed tomography of odontogenic sinusitis. (A) A displaced dental implant into the left maxillary sinus causing sinusitis (White arrow). (B) Oro-antral fistula occurred after right 2nd molar tooth extraction (asterix). |

| Fig. 2The etiologic factors of odontogenic sinusitis. The most common etiologic factor of odontogenic sinusitis was iatrogenic cause such as dental implants and dental extraction. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Medical Research Funds from Kangbuk Samsung Hospital.

References

1. Lopatin AS, Sysolyatin SP, Sysolyatin PG, Melnikov MN. Chronic maxillary sinusitis of dental origin: is external surgical approach mandatory? Laryngoscope. 2002. 112:1056–1059.

2. Mehra P, Murad H. Maxillary sinus disease of odontogenic origin. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004. 37:347–364.

3. Kretzschmar DP, Kretzschmar JL. Rhinosinusitis: review from a dental perspective. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003. 96:128–135.

4. Timmenga NM, Raghoebar GM, Boering G, van Weissenbruch R. Maxillary sinus function after sinus lifts for the insertion of dental implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997. 55:936–939.

5. Kaneko I, Harada K, Ishii T, Furukawa K, Yao K, Takahashi H, et al. [Clinical feature of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis--symptomatology and the grade in development of the maxillary sinus in cases of dental maxillary sinusitis]. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 1990. 93:1034–1040.

6. Ugincius P, Kubilius R, Gervickas A, Vaitkus S. Chronic odontogenic maxillary sinusitis. Stomatologija. 2006. 8:44–48.

7. Lin PT, Bukachevsky R, Blake M. Management of odontongenic sinusitis with persistent oro-antral fistula. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991. 70:488–490.

8. Yoshiura K, Ban S, Hijiya T, Yuasa K, Miwa K, Ariji E, et al. Analysis of maxillary sinusitis using computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1993. 22:86–92.

9. Konen E, Faibel M, Kleinbaum Y, Wolf M, Lusky A, Hoffman C, et al. The value of the occipitomental (Water's) view in diagnosis of sinusitis: A comparative study with computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 2000. 55:856–860.

10. Regev E, Smith RA, Perrott DH, Pogrel MA. Maxillary sinus complications related to endosseous implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1995. 10:451–461.

11. Ueda M, Kaneda T. Maxillary sinusitis caused by dental implants: report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992. 50:285–287.

12. Quiney RE, Brimble M, Hodge M. Maxillary sinusitis from dental osseointegrated implants. J Laryngol Otol. 1990. 104:333–334.

13. Güneri P, Kaya A, Caliskan MK. Antroliths: survey of the literature and a report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005. 99:517–521.

14. Sato K. [Pathology of recent odontogenic maxillary sinusitis and the usefulness of endoscopic sinus surgery]. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 2001. 104:715–720.

15. Iida S, Tanaka N, Kogo M, Matsuya T. Migration of a dental implant into the maxillary sinus. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000. 29:358–359.

16. Block MS, Kent JN. Maxillary sinus grafting for totally and partially edentulous patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993. 124:139–143.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download