Abstract

Purpose

Metaplastic breast carcinoma (MBC) is rare. Its clinicopathologic features and prognosis are uncertain. The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes in comparison with invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC).

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the data of 29 patients with MBC and 4,851 patients with IDC, who received surgery at Yonsei University Severance Hospital between 1980 and 2008. Various clinicopathologic features, recurrence free, and overall survival were investigated and compared to each other.

Results

Stage IV cases at diagnosis were more common in MBC (10.3%) than in IDC (0.9%). The incidence rates of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) were significantly higher in MBC (84.0%) than in IDC (20.1%). Larger tumors (>2 cm) and lower tendency of axillary metastasis were frequently observed in MBC. Only one of 24 preoperative core needle biopsies (CNB) correctly diagnosed MBC. There was no significant difference in survival between the two groups.

Conclusion

MBC was characterized by a higher incidence of TNBC, larger tumor size, and lower tendency of axillary metastasis, and was difficult to diagnose with CNB. Although the incidence of stage IV disease at diagnosis was higher in MBC, the survival rates of stage I-III were comparable to those of IDC.

Metaplastic breast carcinoma (MBC) is a rare type of breast carcinoma that has heterogenous histological elements admixed with adenocarcinoma. MBC differs from typical adenocarcinomas in several pathologic and clinical aspects.

MBC is mainly manifested by a microscopic pattern of spindle cell carcinoma or extensive squamous or pseudosarcomatous metaplasia.1 With regards to nonductal components, MBC is often pathologically subdivided into several distinct subtypes, which include squamous, spindle cell, matrix-producing, carcinosarcoma, etc.2-6 Because of the rarity of these tumors, the pathogenesis is still unknown. The clinicopathologic features are characterized by larger tumor size and lesser lymph node involvement with or without poorer clinical outcomes than those seen with typical breast cancer.7,8 It has been reported that the risk of tumor recurrence of MBC is relatively higher than typical breast cancer; however, this remains controversial.9,10

Recently, MBC has been issued because this neoplasm is usually characterized by a lack of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2/neu) over-expression, which is called 'triple negativity'. Hormone receptor expression in MBC is reported only in 0-26% of cases3,11 and triple negative breast cancer has been known to be resistant to conventional endocrine therapy for hormone receptors positive breast cancer or targeted therapies such as trastuzumab for HER2/neu over-expressing breast cancers.12-16

The purpose of this study was to investigate the clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of MBC in comparison with invasive ductal carcinoma.

We retrospectively reviewed the data of 29 cases with MBC and 4,851 cases with invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), who received surgery at Yonsei University Severance Hospital, between 1980 and 2008. The incidence rates of MBC were calculated using data of 6,313 cases of the Breast Cancer Registry of Yonsei University Severance Hospital, between 1974 and 2008. Three MBC and 43 IDC patients were revealed as cases with distant metastasis at diagnosis.

To compare the clinicopathologic features between the two groups, the following variables were documented: age, subtype, tumor size, nodal status, status of ER and PR, HER2/neu over-expression, operation type, decade of operation, systemic treatment status, preoperative biopsy results, and locoregional or systemic recurrence events.

The cut off value for ER and PR positive was more than 10% staining in immunohistochemisty. Before 1994, the level of the hormone receptor was measured by ligand binding assays, and the positive level was defined as over 3 fmol/mg protein at that time. An immunohistochemistry score of three positive was defined as positive for HER2/neu overexpression.

Five years recurrence free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) rates in both groups were calculated and compared. The RFS rate considered locoregional recurrence and distant recurrence as events, and the events of overall survival were death with any cause. We excluded the cases with distant metastasis at diagnosis in survival analysis.

We used student t-test to calculate mean values in continuous variables and the results were given as mean ± standard deviation. Pearson's Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used for measuring statistical differences in categorical variables and all statistical tests were two-sided. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to plot the RFS and OS rates. Statistical significance was accessed by log-rank test. p < 0.05 is considered to be a statistically significant level. All statistical analysis was performed with PASW statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

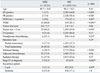

All MBC cases were female. Their mean age at diagnosis was 49 years (range, 28-68), and there were no statistical differences in mean age between both groups. The positive rates of ER, PR, and HER2/neu were 3.7%, 7.4%, and 8.0%, respectively, in the MBC cases. The incidence of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) in MBC was 84%. Tumors larger than 2 cm were more frequent in the MBC group (86.2%) than the IDC group (45.8%, p < 0.001). However, lymph node involvement was less common in MBC than IDC (31.0% vs. 46.6%, p = 0.13). There was no significant difference in operation methods, the rate of performing neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy, and radiation therapy between the groups. Only 20.7% of the MBC cases were treated with endocrine therapy, which differed from the IDC group (20.7% vs. 58.6%, p < 0.001). There were 3 (11.5%) locoregional recurrences and 4 (15.4%) systemic recurrences in the MBC group, and 422 (8.8%) and 816 (17.1%), respectively, in the IDC group. In terms of recurrence rate, there was no statistical difference between the two groups. In contrast, the incidence of stage IV disease at diagnosis was more commonly observed in MBC compared with IDC (10.3% vs. 0.9%, p = 0.002) (Table 1).

There were 7 matrix producing, 1 spindle cell, 4 sarcomatous, 3 squamous, 8 chondroid, and 4 mixed differentiations, and two cases diagnosed in the 1980s without specified subtypes.

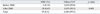

The incidence rate of the MBC was 0.5% of all breast cancers treated at our institute. Among 29 MBC cases, 24 cases (82.7%) were diagnosed between 2000 and 2008, and the incidence rate of MBC significantly increased after 2000 (Table 2).

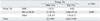

Twenty-one of 24 patients with MBC between 2000 and 2008 were tentatively diagnosed as invasive ductal carcinoma with preoperative core needle biopsy and only one case (4.2%) of them was correctly diagnosed with a preoperative core needle biopsy (Table 3).

The median follow-up time of MBC and IDC cases were 32 and 57 months, respectively. Kaplan-Meier curves for RFS and OS comparing MBC and IDC are illustrated in Fig. 1. Five-year RFS rates of MBC and IDC were 81.5% and 84.1%, and OS rates were 93.3% and 89.1%, respectively. Comparisons of the groups for recurrence-free and overall survival rates revealed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05), and RFS and OS with regard to TNM stage are also not related with histologic type (p > 0.05, data not shown).

MBC is rare and it has been reported that the incidence is less than 1% of all breast malignancies.8,17,18 In this study, the incidence of MBC was 0.5%. Interestingly, about 80% of all cases were diagnosed in the 2000s (0.19% and 0.65% before and after 2000, respectively). The increase of the diagnosis of MBC was consistent with the previous study based on the National Cancer Data Base.19 Barnes, et al.16 also reported a recent increase of MBC and it might be caused by incomplete tumor descriptions and/or misclassification in earlier years compared with the later decade, or by increased recognition of MBC as a distinct breast tumor subtype according to improved diagnostic accuracy or by a true rise in incidence.

As shown in Table 3, only one of 24 was correctly diagnosed MBC with core needle biopsy before surgery, which suggested that it is difficult to make an accurate diagnosis with core needle biopsy. Since MBC consists of at least two distinct histologic components, the volume of samples obtained by core needle biopsy might not be sufficient to distinguish MBC from common types of breast cancers, and this analysis is consistent with a previous study.7

In terms of the incidence of stage IV disease at presentation, 10.3% (3 of 29) of MBC cases were stage IV, which was much higher than 0.9% (43 of 4,851) of IDC at our institute, 2.8% of all registered breast cancers reported by the Korean Central Cancer Registry (KCCR) and Korea Breast Cancer Society Registry (KBCS) data,20 and 2.7-4.9% reported from other previous studies.18,21 The incidence of distant metastasis cases in MBC were reported as 3.3-13.2%.18,22,23 This result might suggest that MBC is more aggressive than other types of breast cancers and the incidence of stage IV disease at presentation is more common. However, because our database only includes data of patients who received surgical treatment, we must be very cautious to interpret the current results as a higher rate of stage IV disease in MBC.

There were six subtypes of MBC in the current study. Breast cancer with chondroid differentiation and matrix producing carcinoma were the most common subtypes, with an incidence of 27.6% and 24.1%, respectively. Description of the subtypes of MBC varies.2-6,8,23 Subtypes of MBC were described as matrix-producing carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, MBC with osteoclastic giant cells, spindle cell metaplasia, adenosquamous carcinoma, MBC with chondroid differentiation, and so on.2-6,16 The molecular analysis also reported the heterogeneity of MBC.24 The prognostic significance of the histologic subtypes in MBC is not established. Oberman suggested that MBC is considered a single entity, but Wargotz, et al. implied that subdivision into multiple histological phenotypes may be related with prognosis.2-6 Because of the small sample size, we could not evaluate the prognosis by subtypes.

MBC is usually regarded as TNBC or basal-like breast cancer (BLBC),12,14,25,26 and the lower positive rates of ER, PR, and HER2/neu overexpression in MBC were observed in numerous studies.7,8,11,16,19,27 TNBC is clinical nomenclature based on hormone receptor and HER2/neu status, and BLBC is defined by a mRNA expression pattern of an intrinsic gene set.28,29 In fact, the TNBC clusters with BLBC, and they are often used as synonyms regardless of the distinctive clinical and molecular complimentary sets. Generally, it has been believed that the prognosis of MBC is relatively poor,7,16,23,30 even though this remains controversial.8,10 Previous studies supported the finding that the poor outcomes of MBC seemed to be associated with triple negativity.7 In addition, others reported that MBC is connected with BLBC for which no specific target therapy is available, and Weigelt, et al. reported that 95% of MBC are BLBC.22,31-33 Our analysis found that MBC showed a trend toward triple negativity, with less than 10% of ER, PR, and HER2/neu positivity, and the incidence of TNBC in MBC is remarka-bly higher than in IDC.

A number of studies have consistently reported that MBC is usually larger than typical breast cancer at presentation.7,9,16,19,34 The mean tumor size in our results was 4.6 cm (range, 1.5-31 cm) and the incidence of tumors larger than 2 cm was 86.2%, which were comparable to previous reports showing larger tumor sizes in MBC than in other types.7,9,16,19,34 The axillary node involvement rate of MBC tended to be lower than that of IDC in this study, which was consistent with other reports showing that MBC is usually associated with a lower incidence of axillary node metastasis, 0-26%, in spite of a larger tumor size than typical breast cancer.2-4,7,8,16,19,23 The reasons why MBC shows a lower rate of nodal involvement in spite of larger tumor size, which may indicate that tumor proliferation mechanism of MBC is somewhat different from that of a typical ductal origin tumor, are of interest. A large-scale transcriptional profiling study revealed that MBC has a few genes that are related with epithelial-mesenchymal transition, which may be recognized as a potential mechanism for the progression of malignancy.35 This previous report is not sufficient to fully explain why MBC shows larger tumor sizes than typical breast cancer, but it may offer clues to understand that there are possibilities of different proliferation mechanisms of MBC compared with typical ductal origin tumors.

In the survival analysis between the two groups, RFS and OS according to the histologic type did not show any statistically significant differences. These findings are consistent with previous studies that reported comparable outcomes with matched typical breast cancer and favorable prognosis.7,8 However, the prognosis of MBC still remains controversial because a series of reports demonstrated that MBC showed more aggressive behavior than typical breast cancer.16,23 In addition, it is of interest that the survival curves appear that almost all of the MBC recurrences occurred during the first five years, whereas for IDC, which is predominantly composed of ER positive patients, the curves continued to fall over time. There is a possibility that MBC may show earlier recurrence than IDC; however, the small size of the events in the MBC group limited further analysis to confirm these results.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Recurrence-free and overall survival according to histologic type of breast cancer in Stage I-III. MBC, metaplastic breast carcinoma; IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma. |

Table 1

Clinicopathological Features between Metaplastic Breast Carcinoma and Invasive Ductal Carcinoma

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Brain Korea 21 Project for Medical Science, Yonsei University College of Medicine and the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (R13-2002-054-03001-0).

References

1. Oberman HA. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast. A clinicopathologic study of 29 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987. 11:918–929.

2. Wargotz ES, Deos PH, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. II. Spindle cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1989. 20:732–740.

3. Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. III. Carcinosarcoma. Cancer. 1989. 64:1490–1499.

4. Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. I. Matrix-producing carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1989. 20:628–635.

5. Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast: V. Metaplastic carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells. Hum Pathol. 1990. 21:1142–1150.

6. Wargotz ES, Norris HJ. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. IV. Squamous cell carcinoma of ductal origin. Cancer. 1990. 65:272–276.

7. Beatty JD, Atwood M, Tickman R, Reiner M. Metaplastic breast cancer: clinical significance. Am J Surg. 2006. 191:657–664.

8. Chao TC, Wang CS, Chen SC, Chen MF. Metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. J Surg Oncol. 1999. 71:220–225.

9. Gutman H, Pollock RE, Janjan NA, Johnston DA. Biologic distinctions and therapeutic implications of sarcomatoid metaplasia of epithelial carcinoma of the breast. J Am Coll Surg. 1995. 180:193–199.

10. Bellino R, Arisio R, D'Addato F, Attini R, Durando A, Danese S, et al. Metaplastic breast carcinoma: pathology and clinical outcome. Anticancer Res. 2003. 23:669–673.

11. Khan HN, Wyld L, Dunne B, Lee AH, Pinder SE, Evans AJ, et al. Spindle cell carcinoma of the breast: a case series of a rare histological subtype. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003. 29:600–603.

12. Reis-Filho JS, Milanezi F, Steele D, Savage K, Simpson PT, Nesland JM, et al. Metaplastic breast carcinomas are basal-like tumours. Histopathology. 2006. 49:10–21.

13. Rakha EA, Ellis IO. Triple-negative/basal-like breast cancer: review. Pathology. 2009. 41:40–47.

14. Korsching E, Jeffrey SS, Meinerz W, Decker T, Boecker W, Buerger H. Basal carcinoma of the breast revisited: an old entity with new interpretations. J Clin Pathol. 2008. 61:553–560.

16. Barnes PJ, Boutilier R, Chiasson D, Rayson D. Metaplastic breast carcinoma: clinical-pathologic characteristics and HER2/neu expression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005. 91:173–178.

17. Tavassoli FA. Classification of metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. Pathol Annu. 1992. 27(Pt 2):89–119.

18. Park JH, Han W, Kim SW, Lee JE, Shin HJ, Kim SW, et al. The clinicopathologic characteristics of 38 metaplastic carcinomas of the breast. J Breast Cancer. 2005. 8:59–63.

19. Pezzi CM, Patel-Parekh L, Cole K, Franko J, Klimberg VS, Bland K. Characteristics and treatment of metaplastic breast cancer: analysis of 892 cases from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007. 14:166–173.

20. Son BH, Ahn SH. Survival Analysis of Korean Breast Cancer Patients Diagnosed between 1993 and 2002 in Korea - A Nationwide Study of the Cancer Registry. J Breast Cancer. 2006. 9:214–229.

21. Kim EY, Lee S, Bae TS, Kim SW, Kwon Y, Kim EA, et al. The clinical characteristics and predictive factors of stage IV breast cancer at the initial presentation: a review of a single institute's data. J Breast Cancer. 2007. 10:101–106.

22. Gilbert JA, Goetz MP, Reynolds CA, Ingle JN, Giordano KF, Suman VJ, et al. Molecular analysis of metaplastic breast carcinoma: high EGFR copy number via aneusomy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008. 7:944–951.

23. Rayson D, Adjei AA, Suman VJ, Wold LE, Ingle JN. Metaplastic breast cancer: prognosis and response to systemic therapy. Ann Oncol. 1999. 10:413–419.

24. Geyer FC, Weigelt B, Natrajan R, Lambros MB, de Biase D, Vatcheva R, et al. Molecular analysis reveals a genetic basis for the phenotypic diversity of metaplastic breast carcinomas. J Pathol. 2010. 220:562–573.

25. Leibl S, Moinfar F. Metaplastic breast carcinomas are negative for Her-2 but frequently express EGFR (Her-1): potential relevance to adjuvant treatment with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors? J Clin Pathol. 2005. 58:700–704.

26. Kim MJ, Ro JY, Ahn SH, Kim HH, Kim SB, Gong G. Clinicopathologic significance of the basal-like subtype of breast cancer: a comparison with hormone receptor and Her2/neuoverexpressing phenotypes. Hum Pathol. 2006. 37:1217–1226.

27. Chhieng C, Cranor M, Lesser ME, Rosen PP. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast with osteocartilaginous heterologous elements. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998. 22:188–194.

28. Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000. 406:747–752.

29. Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001. 98:10869–10874.

30. Luini A, Aguilar M, Gatti G, Fasani R, Botteri E, Brito JA, et al. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast, an unusual disease with worse prognosis: the experience of the European Institute of Oncology and review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007. 101:349–353.

31. Kuroda N, Fujishima N, Inoue K, Ohara M, Hirouchi T, Mizuno K, et al. Basal-like carcinoma of the breast: further evidence of the possibility that most metaplastic carcinomas may be actually basal-like carcinomas. Med Mol Morphol. 2008. 41:117–120.

32. Garcia S, Dalès JP, Charafe-Jauffret E, Carpentier-Meunier S, Andrac-Meyer L, Jacquemier J, et al. Poor prognosis in breast carcinomas correlates with increased expression of targetable CD146 and c-Met and with proteomic basal-like phenotype. Hum Pathol. 2007. 38:830–841.

33. Weigelt B, Kreike B, Reis-Filho JS. Metaplastic breast carcinomas are basal-like breast cancers: a genomic profiling analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009. 117:273–280.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download