Abstract

Kawasaki disease is an acute, self-limiting febrile mucocutaneous vasculitis of infants and young children. Retropharyngeal lymphadenopathy is a rare presentation of Kawasaki disease. We present a case of Kawasaki disease mimicking a retropharyngeal abscess, with upper airway obstruction resulting in delayed diagnosis.

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute, self-limiting febrile mucocutaneous vasculitis of infants and children. Diagnosis of KD is clinical and is based on the presence of fever with other features suggestive of KD, lymphadenopathy being the least common. Retropharyngeal abscess mimicking KD has been rarely reported from India. We discuss an 8-year-old boy presenting initially with a retropharyngeal abscess and upper airway obstruction, later developing a full-blown KD, thus resulting in a delayed diagnosis of KD.

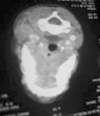

An 8-year-old boy presented with fever, pain on the left side of the neck associated with restricted neck movements, and trismus for 1 day. He also had difficulty in swallowing and breathing. On examination he was febrile (104℉), toxic, anxious, irritable, and a throat examination revealed a 4×5 cm swelling in the posterior pharyngeal wall to the left of the midline. He also had upper deep left cervical lymphadenopathy and there was no cyanosis. His respiratory rate was 48/min, and he had suprasternal indrawing and stridor. His systemic examination was normal. Investigations revealed a total white blood count (WBC) count: 20,800/mm3, polymorphs: 80%, platelet count: 3.5 lacs/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): 55 mm/hr, and a C reactive protein (CRP) of 48 mg/dL. Blood cultures showed no growth. A lateral neck X-ray revealed widening of the retropharyngeal space and narrowing of the upper airway. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck revealed ill-defined hypodense lesion extending from the C2-C6 vertebral level in the posterior pharyngeal space with no contrast enhancement compatible with a diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess (Fig. 1). In light of the high fever and toxemia, he was started on antibiotics (Cefotaxim 100 mg/kg/day) and surgical aspiration was undertaken within 24 hours of the antibiotics and yielded only 2 cc of pus, which were sterile on bacterial cultures. In light of the upper airway obstruction and dysphagia with only a scant aspirate, a tracheostomy was done. His pain reduced post surgery, but the fever and swelling persisted. He was started on amikacin and metronidazole continuing cefotaxim. On day 3, his fever persisted but the swelling reduced in size and there was no dysphasia or respiratory difficulty, and thus he was decannulated and stable. For the next few days he was febrile. During this period the ultrasonography of his abdomen, chest radiograph, echocardiography, and repeat blood and urine cultures were all normal. During the 9th day of his illness, with a persisting fever he developed a bilateral non-purulent bulbar conjunctival injection and erythema of the hands and feet. On the 10th day he developed a polymorphous generalized erythematous rash and a systolic murmur. Investigations at this point in time revealed a total count of 15,100/mm3 with polymorphonuclear leucocytosis, elevated ESR 110 mm/hr, CRP-192 mg/dL, and a platelet count of 9.5 lac/mm3. The repeat echocardiogram revealed a fusiform aneurysm of the proximal and mid right coronary artery 6.5×6 mm. The left main, anterior descending and circumflex coronary arteries were normal. The left ventricular systolic and diastolic functions were normal with an ejection fraction of 68% and a fractional shortening of 37%. There was no pericardial effusion. With these constellation of clinical and laboratory features, the diagnosis of Kawasaki disease was entertained and he was started on intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) 2 g/kg over 24 hours along with aspirin of 100 mg/kg/day. Within 36 hours he became afebrile; his murmur disappeared and he was cheerful. On the follow-up after 14 days he was afebrile, with an ESR of 48 mm/hr, and platelet count of 4.7 lacs/mm3. His repeat echocardiogram (ECHO) at 2 weeks still showed fusiform aneurysmal dilatation of the proximal and mid right coronary artery 6.5×6 mm and he continues to be on a low dose aspirin.

Kawasaki disease is a mucocutaneous vasculitis primarily affecting infants and young children.1 The etiology of KD remains unknown, but clinical and epidemiological studies support an infectious etiology.2 A diagnosis is based on the presence of prolonged fever (more than five days duration) plus four of the following five signs: conjunctival injection, changes in the oral mucous membranes, changes in the peripheries (erythema of the palms and soles, swelling of the hands and feet), rash, and cervical lymphadenopathy. There is no specific diagnostic test for KD and non-specific laboratory findings like thrombocytosis, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate and an elevated CRP may supplement the diagnosis. Lymphodenopathy is the least constant of the diagnostic features of KD occurring in 50-75% of the patients, the other clinical criteria occurring in 90%.3 It has been reported that some patients may not fulfill the above criteria for KD but still develop coronary artery disease and are diagnosed as having incomplete KD.4 Some of the unusual presentations reported in KD include renal impairment,4 acute otitis media, pulmonary infiltrates, abdominal pain, arthritis, lymphadenitis,2 peritonsillar abscess,5 and retropharyngeal abscess. Medline search revealed 6 earlier case reports of KD with an initial presentation of retropharngeal abscess.6-10 CT neck in those cases including the present case revealed hypodense lesions with or without contrast enhancements suggestive of retropharyngeal abscess and cases manifested with signs and symptoms of KD subsequently during the treatment for retropharyngeal abscess. None of the patients in those reports had coronary artery abnormalities in contrast to our patient who had developed aneurysmal dilatation of the right coronary artery.

It is well-known that all criteria for KD need not be present at the same time and can appear in sequence. Thus, the diagnosis of KD in the absence of its typical features needs a high index of clinical suspicion. In our patient, there were no early clues except for a fever and all the criteria for KD only appeared in sequence later. It has been reported that once a patient is diagnosed with KD, the abscess-like lesion on the CT scan should be viewed as a type of inflammation rather than infection11 and this could be one of the reasons why the pus culture was sterile. Early recognition and aggressive medical treatment is crucial to reduce the occurrence of sudden death in adolescence and early adulthood due to coronary artery involvement. Recent studies suggest that in a child with a persistent unexplained fever, the presence of any high parameters of inflammation, anemia, low sodium, and albumin levels should alert clinicians to Kawasaki disease even in the absence of other clinical symptoms.12

In conclusion, Kawasaki disease need not always manifest with all its typical features as in our case where Kawasaki disease mimicked a retropharyngeal abscess. The unusual clinical manifestations of KD reported in previous studies, which were initially clinically missed, are due to the lack of a specific diagnostic test. Hence, a high index of suspicion and careful and repeated examination are needed to prevent dreaded complications of KD.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Stamos JK, Corydon K, Donaldson J, Shulman ST. Lymphadenitis as the dominant manifestation of Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 1994. 93:525–528.

2. Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Kawasaki disease. Nelson textbook of Pediatrics. 2004. 17th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;793–834.

3. Burgner D, Festa M, Isaacs D. Delayed diagnosis of Kawasaki disease presenting with massive lymphadenopathy and airway obstruction. BMJ. 1996. 312:1471–1472.

4. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Pediatrics. 2004. 114:1708–1733.

5. Rothfield RE, Arriaga MA, Felder H. Peritonsillar abscess in Kawasaki disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1990. 20:73–79.

6. Pontell J, Rosenfeld RM, Kohn B. Kawasaki disease mimicking retropharyngeal abscess. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994. 110:428–430.

7. Park AH, Batchra N, Rowley A, Hotaling A. Patterns of Kawasaki syndrome presentation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997. 40:41–50.

8. McLaughlin RB Jr, Keller JL, Wetmore RF, Tom LW. Kawasaki disease: a diagnostic dilemma. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998. 19:274–277.

9. Homicz MR, Carvalho D, Kearns DB, Edmonds J. An atypical presentation of Kawasaki disease resembling a retropharyngeal abscess. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000. 54:45–49.

10. Gross M, Eliashar R, Attal P, Sichel JY. Radiology quiz case 2: Kawasaki disease (KD) mimicking a retropharyngeal abscess. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001. 127:15071508–1509.

11. Hung MC, Wu KG, Hwang B, Lee PC, Meng CC. Kawasaki disease resembling a retropharyngeal abscess--case report and literature review. Int J Cardiol. 2007. 115:e94–e96.

12. Falcini F. Kawasaki disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006. 18:33–38.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download