Abstract

Purpose

Some patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope may be misdiagnosed as epilepsy because myoclonic jerky movements are observed during syncope. The seizure-like activities during the head-up tilt test (HUT) have been rarely reported. The purpose of this study was to assess the characteristics of these seizure-like activities and evaluate whether there are differences in the clinical characteristics and hemodynamic parameters of patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope with and without seizure-like activities during HUT-induced syncope.

Materials and Methods

The medical records of 1,383 consecutive patients with a positive HUT were retrospectively reviewed, and 226 patients were included in this study.

Results

Of 226 patients, 13 (5.75%) showed seizure-like activities, with 5 of these (2.21%) having multifocal myoclonic jerky movements, 5 (2.21%) having focal seizure-like activity involving one extremity, and 3 (1.33%) having upward deviation of eye ball. Comparison of patients with and without seizure-like activities revealed no significant differences in terms of clinical variables and hemodynamic parameters during HUT.

Syncope is usually defined as a sudden, transient loss of consciousness, from which a patient spontaneously recovers. It occurs across all age groups. Neurally mediated reflex syncope is a common cause of this loss of consciousness and is characterized by excessive vagal tone and sympathetic withdrawal.1 The head-up tilt test (HUT) is used to diagnose neurally mediated reflex syncope; however, neurally mediated reflex syncope may be misinterpreted as epilepsy and treated with anticonvulsant drugs because myoclonic jerky movements or upward deviation of eye ball may be observed during syncopal events.2,3 A study of convulsive syncope in blood donors reported that convulsive syncope occurred in 0.03% of all blood donors.4 The incidence of neurological manifestations in syncopal subjects was 11.9% by retrospective analysis and 41.6% by prospective analysis.4 Seizure-like activities during HUT was reported in 67% of selected patients with recurrent seizure-like episodes.5 However, seizure-like activities during HUT in patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope has not been well established.

The purpose of this study was to assess the incidence and characteristics of seizure-like activities during HUT-induced syncope in patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope. We also evaluated whether there were differences in clinical characteristics and hemodynamic parameters during HUT between patients with and without seizure-like activities.

One thousand three hundred eighty-three consecutive patients with suspected neurally mediated reflex syncope, who showed a positive response of HUT, were recruited at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea between October 1994 and October 2004. The medical records and HUT case report forms of 1,383 consecutive patients were retrospectively reviewed. Of 1,383 patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope, 226 patients, who experienced syncope during HUT and did not have any other cause of syncope, were included in this study. However, 1,157 patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope were excluded from the study because they did not lose their consciousness during HUT. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Ethnics in Medical Research.

After obtaining informed consent, HUT was performed on patients who had fasted for four hours, as previously described.6 The first phase of HUT was performed with patients tilted to an angle of 70° for 30 minutes, or until symptoms appeared. If the first phase of HUT was negative, the second phase of HUT, with isoproterenol stimulation, was initiated while patients were kept in the same 70° upright posture as in the first phase. Isoproterenol was intravenously administered at an initial rate of 1 µg/min. The infusion rate was increased by 1 µg/min every three minutes, to a maximum of 5 µg/min. During the HUT, we conducted continuous ECG monitoring of heart rate and cardiac rhythm, and each patient's blood pressure was noninvasively measured beat-to-beat using a Finapres (OhMeda Monitoring System, Englewood, CO, USA). A positive response to HUT was defined when syncope or presyncope was reproduced in association with hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 80 mmHg), bradycardia (a sinus arrest > 3 seconds or heart rate < 45 beats/min in the first phase, < 60 beats/min in the second phase), or both. Positive responses were classified according to the criteria provided in a previous study: type 1 (mixed), type 2 (cardioinhibitory), and type 3 (vasodepressive). Asystole was defined as a pause lasting longer than 3 seconds.7

Seizure-like activities were defined as myoclonic jerky movements or upward deviation of eye ball. Myoclonic jerky movements were classified as focal myoclonic jerky movements involving one extremity or multifocal myoclonic jerky movements involving more than one extremity during HUT-induced syncope.3

We retrospectively reviewed HUT case report forms to collect data of seizure-like activities during HUT-induced syncope. Seizure-like activities were described by attending internal medicine residents during HUT.

The patients were divided into two groups for analysis: 1) patients with seizure-like activities during HUT, and 2) patients without seizure-like activities during HUT. The clinical characteristics and hemodynamic parameters of two groups during HUT were examined and compared.

Means were calculated for continuous variables and the frequency was measured for categorical variables. Comparisons were made by Student's t-test for continuous variables, and the chi-square test was used for categorical variables. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 11.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with Windows 2000 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA).

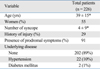

The study included 226 patients (102 men, 124 women; mean age 39 ± 15 years). The mean number of syncopal episodes was 4 ± 9. Six patients (29%) suffered physical injury during a syncopal episode, 205 patients (91%) had prodromal symptoms before a syncopal episode, 202 patients (89%) did not have any underlying disease, 22 patients (10%) had hypertension, and two patients (1%) had diabetes mellitus (Table 1).

Of the 226 patients who experienced syncope during HUT, 13 patients (5.75%) showed seizure-like activities during HUT-induced syncope. Of the 13 patients with seizure-like activities, 5 (2.21%) had apparent multifocal myoclonic jerky movements, 5 (2.21%) had focal myoclonic jerky movements, and 3 (1.33%) showed upward deviation of eye ball.

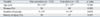

Comparison of the two groups of patients with and without seizure-like activities during HUT revealed no significant differences in patients age, gender distribution, number of syncopal episodes, proportion of underlying disease, or history of physical injury from syncope (Table 2).

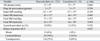

Comparison of the two groups of patients with and without seizure-like activities during HUT revealed no significant differences in tilt duration, isoproterenol infusion rate, hemodynamic parameters during HUT (initial systolic blood pressure, initial heart rate, final systolic blood pressure, final heart rate), proportion of provoked asystoles, or the pattern of positive HUTs (Table 3).

Seizure activities develop in patients with epilepsy. However, cardiovascular disease and neurally mediated reflex syncope may also cause seizure-like activities during syncopal episodes, leading to an incorrect diagnosis of epilepsy. Grubb, et al.5 showed a positive response to HUT in 10 of 15 patients (67%) with recurrent, unexplained seizure-like activities, who were unresponsive to anticonvulsant drugs.

In this study, seizure-like activities occasionally occurred during HUT-induced syncope in patients with neurally mediated syncope. A previous study reported that the incidence of seizure-like activities during HUT was 8% in patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope,8 similar to the result in this study. We also showed a diverse pattern of seizure-like activities, including multifocal myoclonic jerky movements (2.21%), focal myoclonic jerky movements (2.21%), and upward deviation of eye ball (1.33%).

Differentiation of neurally mediated syncope from epilepsy is not easy in patients with convulsive syncope. Based on symptoms alone, however, Sheldon, et al.9 proposed a simple point score in distinguishing syncope from epilepsy with very high sensitivity and specificity. Zaidi, et al.10 reported that an alternative diagnosis was found in 31 of 74 patients (41.9%) with epilepsy. They used several diagnostic tests including HUT, carotid sinus massage, electroencephalography (EEG), and implantable loop recorder. Nineteen patients (25.7%) showed a positive response to HUT, confirming the diagnosis of neurally mediated syncope.

The effect of blood pressure and heart rate on the occurrence of seizure-like activities is not well established. Lin, et al.4 reported that in blood donors, no significant difference in the changes of blood pressure or pulse was found between subjects with convulsive syncope and those with nonconvulsive syncope, and Passman, et al.8 showed that patients with multifocal or generalized myoclonic jerky movements had a significantly lower systolic blood pressure at the termination of HUT than other patients; heart rate at the termination of HUT was significantly lower in patients with seizure-like activities than in those without seizure-like activities, and asystole was more frequently noted in patients with seizure-like activities.

The definition and classification of positive response of our HUT was refered to Brignole's paper7 rather than Vasovagal Syncope International Study (VASIS) study group11. Our HUT protocol used intravenous isoproterenol infusion during the second phase of HUT. Therefore, our HUT protocol might affect the incidence of asystolic response during HUT. However, we did not see any significant difference between the subjects with and without seizure-like activities in terms of asystole. Our study also did not show any significant differences in clinical characteristics and hemodynamic parameters at the termination of HUT between the subjects with and without seizure-like activities.

Cerebral ischemia secondary to hypotension, bradycardia, or both, is an important contributing factor in provoking seizure-like activities during HUT-induced syncope in patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope. However, cerebral autoregulation in response to hemodynamic changes showed great individual variations.12,13 Stern and Tzivoni14 reported a patient with prolonged cardiac arrest who felt dizziness without convulsive syncope. Therefore, a great individual variation in the reaction of the brain to ischemia may explain the lack of significant differences in clinical characteristics and hemodynamic parameters at the termination of HUT between the subjects with and without seizure-like activities in this study.

EEG monitoring during HUT could give useful information to help understand seizure-like events occurring during HUT-induced syncope in patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope. In patients with myoclonic jerky movements during HUT-induced syncope, EEG showed theta and delta wave slowing without spike or spike-wave activity.15 However, simultaneous EEG recording was not performed in this study.

Seizure-like activities occasionally occurred during HUT-induced syncope in patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope. Therefore, we have to recognize the occurrence of seizure-like activities and are very cautious not to misdiagnose epilepsy in patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope.

This study was retrospective in design. Of 1,383 patients, only 226 were included, whereas 1,157 patients were excluded from the study because they did not lose consciousness during HUT. We did not have the chance to observe the seizure-like activities in these excluded patients because they were rapidly lowered to a horizontal position after showing a positive response to HUT.

We could not collect the seizure-like activities in patient's natural history of syncope. Therefore, we could not assess the relationship between the seizure-like activities during HUT and the seizure-like activities in the natural history of syncope.

Although seizure-like activities occasionally occurred during HUT-induced syncope in our patients with neurally mediated reflex syncope, the seizure-like activities might not be related to the severity of the syncopal episodes or hemodynamic changes during HUT. Therefore, further study is needed to elucidate the relationship between the occurrence of seizure-like activity and clinical characteristics and hemodynamic changes in a larger patient population.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Grubb BP. Pathophysiology and differential diagnosis of neurocardiogenic syncope. Am J Cardiol. 1999. 84:3Q–9Q.

2. Fejerman N. Nonepileptic disorders imitating generalized idiopathic epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2005. 46:Suppl 9. 80–83.

3. Lempert T, Bauer M, Schmidt D. Syncope: a videometric analysis of 56 episodes of transient cerebral hypoxia. Ann Neurol. 1994. 36:233–237.

4. Lin JT, Ziegler DK, Lai CW, Bayer W. Convulsive syncope in blood donors. Ann Neurol. 1982. 11:525–528.

5. Grubb BP, Gerard G, Roush K, Temesy-Armos P, Elliott L, Hahn H, et al. Differentiation of convulsive syncope and epilepsy with head-up tilt testing. Ann Intern Med. 1991. 115:871–876.

6. Kim PH, Ahn SJ, Kim JS. Frequency of arrhythmic events during head-up tilt testing in patients with suspected neurocardiogenic syncope or presyncope. Am J Cardiol. 2004. 94:1491–1495.

7. Brignole M, Menozzi C, Gianfranchi L, Oddone D, Lolli G, Bertulla A. Carotid sinus massage, eyeball compression, and head-up tilt test in patients with syncope of uncertain origin and in healthy control subjects. Am Heart J. 1991. 122:1644–1651.

8. Passman R, Horvath G, Thomas J, Kruse J, Shah A, Golderberger J, et al. Clinical spectrum and prevalence of neurologic events provoked by tilt table testing. Arch Intern Med. 2003. 163:1945–1948.

9. Sheldon R, Rose S, Ritchie D, Connolly SJ, Koshman ML, Lee MA, et al. Historical criteria that distinguish syncope from seizures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002. 40:142–148.

10. Zaidi A, Clough P, Cooper P, Sheepers B, Fitzpatrick AP. Misdiagosis of epilepsy: many seizure-like attacks have a cardiovascular cause. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000. 36:181–184.

11. Brignole M, Menozzi C, Del Rossa A, Costa S, Gaggioli G, Bottoni P, et al. New classification of hemodynamics of vasovagal syncope: beyond the VASIS classification. Analysis of the presyncopal phase of the tilt test without and with nitroglycerin challenge. Vasovagal Syncope International Study. Europace. 2000. 2:66–76.

12. Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1990. 2:161–192.

13. Carey BJ, Manktelow BN, Panerai RB, Potter JF. Cerebral autoregulatory responses to head-up tilt in normal subjects and patients with recurrent vasovagal syncope. Circulation. 2001. 104:898–902.

14. Stern S, Tzivoni D. Atrial and ventricular asystole for 19 seconds without syncope. Report of a case. Isr J Med Sci. 1976. 12:28–33.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download