Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study is to define the clinical implications of consolidations in nodular bronchiectatic type Mycobacterium avium complex (NB-MAC) infection.

Materials and Methods

A total of 69 patients (M : F = 17 : 52; mean age, 64 years; age range, 41-85 years) with MAC isolated in the sputum culture and nodular bronchiectasis on the initial and follow-up CT scans were included. We retrospectively reviewed the incidence of consolidation and analyzed its clinical course by using radiographic changes with or without anti-MAC drug therapy.

Results

In 44 of the 69 cases (64%), focal consolidations were seen on the initial and follow-up CT images. In 35 of the 44 (80%) cases, consolidations completely regressed, and in 3 cases (7%), consolidations partially regressed within 2 months with only antibiotics. In 2 cases (5%), the consolidations remained stable for over 2 months without anti-MAC drug therapy. Only in 4 cases (9%) did the consolidations improve after anti-MAC drug therapy. In 11 of the 38 cases (29%) with responsiveness to antibiotics, non-mycobacterial micro-organisms were identified in sputum, including pseudomonas, hemophilus, staphylococcus, and others.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection (NTM) mainly occurs due to the inhalation of organisms which are present in the environment. In immunocompetent patients, the occurrence rate has been gradually increasing as the major cause of chronic infection.1 Of these, mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is one of the most common worldwide human pathogens causing NTM, and it accounts for more than 70% of pathogens causing NTM lung disease.2-4

MAC lung disease is divided into two subtypes, cavitary type and nodular bronchiectatic type, each of which has been reported to feature different clinical presentations and radiologic manifestations.1 The cavitary type is observed to be a heterogeneous nodular with cavitary opacities involving upper lobe on CT scans, and it occurs in elderly male patients with a smoking history or those who had underlying lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or pulmonary fibrosis. In contrast, the nodular bronchiectatic type MAC (NB-MAC) occurs in elderly women who lack any underlying lung disease. In these patients, the characteristic CT findings include cylindrical bronchiectasis and centrilobular nodules with tree in bud. These findings are particularly seen in the middle lobe or lingula. In addition, there can also be such findings as consolidation and cavitation.5-7 Of these, bronchiectasis and cavitation in the related histopathologic findings as well as CT findings have been well documented. With regards to the consolidation, however, there were reports about various incidences. But, its significance or histopathological findings have rarely been described.8-11 Given this background, we attempted to clarify the clinical implications of consolidations of NB-MAC.

Between May 2003 and December 2007, 119 patients with MAC (M : F = 42 : 77; mean age 64, years; age range, 41-87 years) underwent a CT scan in our institute. An initial chest CT scan was performed for without underlying lung diseases or differentiating from MAC mimicking diseases such as tuberculosis or diffuse panbronchiolitis. A follow-up CT scan was obtained in patients with progressive symptoms or new lesions on a plain chest radiography. Sixty nine patients of 119 (M : F = 17 : 52; mean age, 64 years; age range, 41-85 years) showed nodules and bronchiectasis in the lung on the CT scans. All patients were immunocompetent. We checked the presence of consolidation on the CT scans of 69 patients with NB-MAC and at this time, consolidation was defined as a homogeneous increase in pulmonary parenchymal attenuation that obscured the margins of vessels and airway walls according to the Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society.12

Incidence of consolidation and its clinical course were analyzed using radiographic changes with or without anti-NTM chemotherapy. Exclusively in patients with consolidation, their clinical courses were classified as the group where there was NTM medication and where there was a lack of it. Incidence of consolidation on the initial CT scan and newly identified consolidation on the follow-up (FU) CT was analyzed. In patients with consolidation, their clinical courses with empirical antibiotic treatment only or anti-NTM chemotherapy were analyzed using radiographic changes. In each group, follow-up images were taken within a 2-month period. Based on these follow-up images, each group was divided into the responder group where there was a change and the non-responder group where there was a lack of change. All these patients fulfilled the 1997 American Thoracic Society criteria for the diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. The Institutional Review Board of our institution approved this retrospective study.

Two CT scanners (Volume Zoom, Siemens, Forchheim, Germany; LightSpeed, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) were used. All scans were reconstructed into axial images with 5-mm slice thickness at 5-mm intervals. Both unenhanced and contrast-enhanced images were obtained. Two radiologists retrospectively reviewed the CT images with a consensus on a 2,048×2,560 Picture Archiving and Communication Systems Monitor (PACS; Marotech, Seoul, Korea).

In 44 of 69 cases (64%), consolidations were seen on CT images. Of these, 14 cases had a consolidation detected on the initial CT (Figs. 1 and 2). In the remaining 30 cases, a consolidation was newly identified on the FU CT while only a nodular bronchiectasis was identified on the initial CT (Figs. 3 and 4). The mean follow-up interval between the period during which an initial CT diagnosis of NTM and the time of a new consolidation on the CT was performed and a follow-up CT based on which a consolidation was newly identified was 19 months (2-47 months).

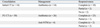

Of the 44 patients, 40 underwent empirical treatment with antibiotics. Macrolide therapy was not introduced in most cases. In a total of 95% of patients with empirical treatment (38/40), a regression of the consolidation was achieved within two months. Of these patients of the antibiotics responder group, 35 patients (88%, 35/40) showed that a consolidation completely regressed (Figs. 1 and 3). In three patients (7%, 3/40), it partially regressed. Of these, such non-NTM bacterial strains as pseudomonas, hemophilus and staphylococcus were isolated on the sputum culture in 11 cases. In 2 cases (5%, 2/40), the consolidations were not responsive to antibiotics; however, they remained stable for over 2 months without anti-MAC chemotherapy (Fig. 2).

Anti-NTM chemotherapy with macrolides was initiated in four residual patients under consideration of disease progression, and consolidation completely regressed in two patients and partially regressed in two patients in 2 months (Fig. 4) (Table 1). Anti-NTM chemotherapy was maintained using 12 months of culture negativity as the treatment end point.

The responsiveness to the antibiotics or anti-NTM chemotherapy is summarized in Table 1.

In cases of NB-MAC, centrilobular nodules and cylindrical bronchiectasis are typical CT findings. A histopathological background of these findings has been well documented. The characteristic pathological finding of MAC lung disease was extensive granuloma formation from the large airway to the bronchiole. In the bronchiole, a peribronchial granuloma protruded into the lumen which resulted in the narrowing of the bronchiole. In addition, ulceration of the bronchial wall with ensuing disruption of the muscle layer was frequently observed, which may have caused bronchiectatic changes. Centrilobular nodules might have been caused by transbronchial dissemination of necrotic materials found in the lumen of the bronchiole.8-11

NB-MAC shows a tendency that symptoms are of mild severity and it has a slow progression. It therefore requires the time extending from approximately 5 years to 10 years. Accordingly, the treatment decision on MAC lung disease is commonly made following a careful interpretation of the patients' overall status and each respiratory MAC isolate. In an actual clinical setting, prior to the suspicion of disease progression, a monitoring of the clinical courses is routinely done without specific treatments. Accordingly, in patients with NB-MAC, the changes in the radiologic findings can be objective evidence suggestive of disease progression. It can therefore be an important indicator for determining anti-MAC therapy. Actually, according to Wickremansinghe, et al., bronchiectasis was aggravated on CT findings in some patients with NB-MAC for whom the treatment was performed. Besides, there were also findings of cavities and consolidation.1,13

In patients with NB-MAC, although rare, there can be a concurrent presence of cavitation or consolidation. In cases in which there is a cavitary lesion, the inflammation progressed to the adjacent region to bronchiectasis. Otherwise, it has been known as a mixed form of a cavitary type and nodular bronchiectatic type. According to Kim, et al.,9 the cavitary lesion of MAC lung disease occurred due to the formation of large cystic bronchiectasis after inflammation developed in a nodular bronchiectatic form. According to Okumura, et al.,14 however, nodular bronchiectatic type can be aggravated but it will not progress to the cavitary lesion. However, it triggers the occurrence of repeated bronchogenic spread around the main focus.

On the other hand, the frequency or histopathologic findings of consolidation have rarely been reported. This might be because a surgical approach cannot be easily completed considering the clinical characteristics of NB-MAC. There are reports about incidences of consolidation, most of which have described as the cavitary type together with the nodular bronchiectatic type.8,9,15 Jeong, et al.8 performed a correlation analysis using a lobectomy specimen. These authors reported that a consolidation was centrally located caseating granulomas and marginal non-specific inflammation. Fujita, et al.11 reported that it had loosely grouped granulomas and/or coalescent inflammatory infiltrates completely replaced normal alveoli, edema, and congestion in alveolar lesions adjacent to the granulomas. However, these authors did not differentiate between these two subtypes of MAC lung disease.

Before starting the present study, we have concentrated on the consolidation whose concurrent presence was newly found to be at a follow-up in patients with NB-MAC. Then, we have also speculated that NB-MAC disease progression might be indicated based on the consolidation which was newly developed or concurrently present at the time of the initial diagnosis during a monitoring of the clinical courses in patients with NB-MAC. It is difficult to histopathologically demonstrate all the consolidations that have been observed in patients with MAC. In most of the patients, however, prior to the initiation of MAC chemotherapy, based on whether conservative or antibiotic therapy would be performed, the presence of responses was assessed.

In our series, the proportion of cases in which a consolidation was observed at the time of the initial diagnosis or during a monitoring of the clinical courses amounted to 64%. These results indicate that the frequency is relatively higher. Of these, 87% had improved symptoms only after empirical antibiotic treatment within 2 months. These responses indicate that a consolidation is pneumonia originating from other causes rather than granulomatous inflammation in patients with NB-MAC. Besides, this implies that a newly developed consolidation is not an image finding which is suggestive of disease progression.

The limitations of the current study include selection bias. Firstly, usual clinical presentations of NB-MAC are mild chronic cough or productive sputum, although the symptoms are variable and nonspecific. Based on the clinical characteristics of NB-MAC, most of the cases are asymptomatic. However, in patients who visited our medical institution, there were many cases in which new symptoms or progressive symptoms developed. Accordingly, many patients with superimposed pneumonia were included in our study. Secondly, the conclusions were drawn from the presence of treatment response to the isolated bacterial strains and antibiotics rather than a direct comparison with the histopathological findings. Considering the clinical courses of NB-MAC, a surgical approach could not be made. Actually, in most of the patients, consolidation improved. Thus, a histopathological demonstration could not be made.

Consequently in cases of NB-MAC, bronchial and peribronchial inflammation mainly occurs and this leads to the subsequent occurrence of bronchiectasis with centrilobular nodules. But there are rare cases in which a consolidation occurs due to lung parenchymal invasion of MAC in NB-MAC. Besides, a consolidation which occurs during a follow-up study cannot be considered disease progression. Before attempting anti-MAC chemotherapy, the conservative or empirical antibiotic treatments would be of great help.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1A 45-year-old woman with NB-MAC, initially presenting with consolidation. (A) Plain chest radiography shows an ill-defined ovoid consolidation in left middle lung zone (arrow). (B) Initial CT scans shows mild cylindrical bronchiectasis and adjacent centrilobular nodules in right middle lobe and lingula, suggestive of NB-MAC. A focal consolidation is seen in subpleural region of lingula (double arrows). (C) FU plain radiography after 2 weeks shows disappearance of the prior focal consolidation after antibiotic therapy. NB-MAC, nodular bronchiectatic type Mycobacterium avium complex; FU, follow-up. |

| Fig. 2A 48-year-old man with NB-MAC, who had a consolidation without response to antibiotics. (A and B) Initial CT shows multifocal clusters of centrilobular nodules with tree in bud appearance in right upper and middle lobes and lingula (arrowheads). Peripheral airways of right upper lobe are minimally dilated (thin arrow). A focal consolidation is seen at anterior subpleural region of lingula (arrow). (C) Two-month FU CT shows little change in size of the prior consolidation in lingula (double arrows) after empirical antibiotics. NB-MAC, nodular bronchiectatic type Mycobacterium avium complex; FU, follow-up. |

| Fig. 3A 53-year-old women with NB-MAC, who had newly detected consolidations during FU period managed with empirical antibiotic therapy. (A) Initial CT shows bronchiectasis with atelectasis and nearby clustered micronodules in right middle lobe. Faint nodular opacities are also visible at posterior aspect of right lower lobe (arrowheads). (B) Six-month FU HRCT at the same level to A shows a new irregular consolidation at posterior subpleural region of right lower lobe (arrow). Another smaller consolidation is seen in right middle lobe (double arrows). Bronchiectasis and clustered centrilobular nodules of right middle lobe, indicative of NB-MAC, are more clearly demarcated than before. The pre-existing faint nodules of right lower lobe are invisible, suggestive of improvement of focal bronchiolitis. (C) One-month FU HRCT after antibiotic therapy shows complete regression of the prior consolidations in right middle and lower lobes. NB-MAC, nodular bronchiectatic type Mycobacterium avium complex; FU, follow-up; HRCT, high-resolution CT. |

| Fig. 4A 72-year-old man with NB-MAC, who had newly detected consolidations during FU with response to anti-MAC therapy. (A) Axial CT shows multifocal cylindrical bronchiectasis and centrilobular nodules with volume loss in both lungs. Irregular consolidations are seen at posterior aspect of right lower lobe (arrow). Anti-MAC therapy was initiated. (B) Plain radiograph obtained at the same day to A shows multifocal consolidations and small nodular opacities in right lung and left lower lung zone. (C) FU plain radiography after 2 months shows decreased extent of the consolidations and nodules of both lungs. NB-MAC, nodular bronchiectatic type Mycobacterium avium complex; FU, follow-up. |

References

1. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was approved by the Board of Directors, March 1997. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997. 156:S1–S25.

2. Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Lee KS. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases in immunocompetent patients. Korean J Radiol. 2002. 3:145–157.

3. O'Brien RJ, Geiter LJ, Snider DE Jr. The epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases in the United States. Results from a national survey. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987. 135:1007–1014.

4. Tsukamura M, Kita N, Shimoide H, Arakawa H, Kuze A. Studies on the epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteriosis in Japan. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988. 137:1280–1284.

5. Prince DS, Peterson DD, Steiner RM, Gottlieb JE, Scott R, Israel HL, et al. Infection with Mycobacterium avium complex in patients without predisposing conditions. N Engl J Med. 1989. 321:863–868.

6. Reich JM, Johnson RE. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease presenting as an isolated lingular or middle lobe pattern. The Lady Windermere syndrome. Chest. 1992. 101:1605–1609.

7. Koh WJ, Lee KS, Kwon OJ, Jeong YJ, Kwak SH, Kim TS. Bilateral bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis at thin-section CT: diagnostic implications in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Radiology. 2005. 235:282–288.

8. Jeong YJ, Lee KS, Koh WJ, Han J, Kim TS, Kwon OJ. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection in immunocompetent patients: comparison of thin-section CT and histopathologic findings. Radiology. 2004. 231:880–886.

9. Kim TS, Koh WJ, Han J, Chung MJ, Lee JH, Lee KS, et al. Hypothesis on the evolution of cavitary lesions in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection: thin-section CT and histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005. 184:1247–1252.

10. Fujita J, Ohtsuki Y, Shigeto E, Suemitsu I, Yamadori I, Bandoh S, et al. Pathological findings of bronchiectases caused by Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex. Respir Med. 2003. 97:933–938.

11. Fujita J, Ohtsuki Y, Suemitsu I, Shigeto E, Yamadori I, Obayashi Y, et al. Pathological and radiological changes in resected lung specimens in Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex disease. Eur Respir J. 1999. 13:535–540.

12. Austin JH, Müller NL, Friedman PJ, Hansell DM, Naidich DP, Remy-Jardin M, et al. Glossary of terms for CT of the lungs: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 1996. 200:327–331.

13. Wickremasinghe M, Ozerovitch LJ, Davies G, Wodehouse T, Chadwick MV, Abdallah S, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria in patients with bronchiectasis. Thorax. 2005. 60:1045–1051.

14. Okumura M, Iwai K, Ogata H, Ueyama M, Kubota M, Aoki M, et al. Clinical factors on cavitary and nodular bronchiectatic types in pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease. Intern Med. 2008. 47:1465–1472.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download