Abstract

A patient received combined spinal-epidural anesthesia for a scheduled total knee arthroplasty. After an injection of spinal anesthetic and ephedrine due to a decrease in blood pressure, the patient developed a severe headache. The patient did not respond to verbal command at the completion of the operation. A brain CT scan revealed massive subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhages, and a CT angiogram showed a ruptured aneurysm. Severe headaches should not be overlooked in an uncontrolled hypertensive patient during spinal anesthesia because it may imply an intracranial and intraventricular hemorrhage due to the rupture of a hidden aneurysm.

Asymptomatic aneurysms are difficult to diagnose. However, fatality due to a ruptured aneurysm is high, and prognosis is poor for survivors.1 The cause of a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a ruptured aneurysm in 85% of cases.2 Classically, the headache from an aneurysmal rupture develops in seconds,1 and it is known to rupture under conditions associated with sudden rises in blood pressure.3 Even the headache after a dural puncture needs a thorough assessment because it may indicate life-threatening intracranial problems.

A 66-year-old, 160 cm, 48 kg man was scheduled to undergo a total knee arthroplasty. His medical history revealed a ten-year history of diabetes mellitus (DM), uncertain hypertension history, and previous knee surgery. The patient suffered from occasional dyspnea and chest discomfort. An ECG showed a sinus bradycardia of 57 bpm and a 99-m Tc-MIBI scan was normal. Laboratory tests showed glucose 4+ on urinalysis, HbA1c 10.0%, and serum glucose around 200-300 mg/dL.

At the pre-anesthesia preparation room, ECG and pulse oximetry were applied and blood pressure (BP) was measured non-invasively at 5-min intervals. The initial BP was 104/56 mmHg with a heart rate (HR) of 57 bpm. Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia was administered using a 17-gauge Tuohy needle and 27-gauge Whitacre spinal needle at the level of the L3-4 interspace under standard aseptic conditions. Upon the first attempt, the epidural space was found using a loss of resistance technique, and clear cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was obtained after spinal needle insertion. There were no paresthesias. A total of 2.0 mL of 0.5% tetracaine, mixed with saline, the patient's CSF, and epinephrine 1 : 200,000, was administered slowly to the patient. An epidural catheter was inserted without resistance and advanced 5 cm upward (by having the bevel of the needle pointed cephalad) and a sensory block to T12 was achieved by a pin-prick test. Then, BP dropped to 87/46 mmHg, and the sensory block was checked at T6. Ephedrine hydrochloride 12 mg and 20 mg was administered intravenously and intramuscularly, respectively. BP raised to 120/65 mmHg, and the patient was transferred to the operating room. In the operating room, BP was 147/69 mmHg and rose to 153/79 mmHg after turning a tourniquet on. Then, the patient complained of a sudden onset of a severe headache and became restless. The BP recorded at the onset of the headache was 190/123 mmHg, and HR was 75 bpm. No ECG changes were noted. Labetalol hydrochloride (10 mg) was injected, and, to sedate the patient, midazolam (2 mg) was injected, but the patient was still irritable. Then, thiopental sodium (100 mg) was injected via IV. BP was maintained around 160/65 mmHg for an hour before a sudden tachycardia of 140 bpm and BP of 200/97 mmHg was observed. Lidocaine (80 mg) was injected and isosorbide dinitrate infusion began due to ST depression. The patient was semi-comatose with asymmetric pupils. BP gradually decreased and was maintained around 105/60 mmHg. After taking a brain CT scan, the patient was transferred to the ICU.

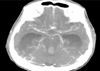

The brain CT showed a large amount of SAH and an intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) (Fig. 1), and a CT brain angiogram showed a 6-mm ruptured intracranial aneurysm at the anterior communicating cerebral artery (ACOM) and a 4-mm unruptured cerebral aneurysm at the left middle cerebral artery bifurcation (Figs. 2 and 3). GDC coil embolization at the ACOM was performed, and external ventricular drainage was carried out. The patient was transferred to the ICU for observation.

The patient was semi-comatous without light reflex, and pupils were asymmetric. BP was maintained by infusing dopamine, vasopressin, and levophad. The patient fell into a coma, unable to maintain stable vitals, and died 17 days after the surgery.

Spontaneous SAH is a rare event, caused primarily by a rupture of a cerebral aneurysm, and the estimated incidence of SAH is 8-10 cases per 100,000 persons per year.4 An incidental finding of cerebral aneurysm on a brain MRI is 1.8%,5 and the incidence increases with age.6 We present a case where the sudden rupture of an aneurysm occurred while undergoing a well-managed spinal anesthesia. A careful diagnosis should be made when one confronts a headache after spinal anesthesia.

The differential diagnoses for a severe headache in combination with a dura puncture include post-dural puncture headache, migraine, drug-induced headache, pneumocephalus, and intracranial pathologies.7,8 In our patient, the procedure itself was completed on the first attempt and a 27-gauge hole in the dura could not have caused significant CSF loss. The dura could have been torn during epidural catheter insertion, but we did not observe any CSF leakage through the catheter. Böttiger, et al.9 reported that the loss of CSF from the puncture site decreases CSF pressure and increases transmural pressure across the arterial wall, which could be some predisposing factors for the rupture of a preexisting cerebral aneurysm. Also, ephedrine was given due to decreased BP. Aneurysms are known to rupture under conditions associated with sudden rises in blood pressure.3 These sudden swings in blood pressure could have facilitated the rupture of a potentially weakened vessel wall. Moreover, we later discovered that the patient was irregularly taking anti-hypertensive pills. This could have jeopardized cerebral autoregulation in addition to cerebral vasculature changes caused by DM. DM causes vascular remodeling which increases the incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular, peripheral vascular, and cerebrovascular disease in patients.10,11 These structural and functional modifications in the cerebral small vessels impair autoregulation of the cerebral blood flow which causes cerebral vessels to respond inappropriately to stimuli affecting cerebrovascular hemodynamics.2 It is probable that the aneurysm ruptured when the patient complained of a severe headache because a headache from an aneurysmal rupture develops in seconds,1 and a sudden increase in regional intracranial pressure causes the sudden onset of severe headache.12 On the other hand, spinal anesthetic and SAH might have been purely incidental, considering that many spontaneous SAHs occur without obvious triggering events.

Considering the sequence of events, the increase in blood pressure was not appropriately managed by impaired cerebral vasculature, which probably led to the rupture of the hidden aneurysm.

Therefore, vasopressors should not be loosely employed for the control of hypotension in a patient with cardiovascular disease, and symptoms such as a headache should be evaluated carefully.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1CT scan of a brain showing a large amount of subarachnoid hemorrhage and intraventricular hemorrhage. |

References

1. van Gijn J, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage: diagnosis, causes and management. Brain. 2001. 124:249–278.

3. Pulsinelli WA. Bennett JC, Plum F, editors. Cerebrovascular diseases, aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cecil's textbook of medicine. 1996. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders;2073–2076.

4. Wijdicks EF, Kallmes DF, Manno EM, Fulgham JR, Piepgras DG. Subarachnoid hemorrhage: neurointensive care and aneurysm repair. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005. 80:550–559.

5. Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, Vincent AJ, Hofman A, Krestin GP, et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 2007. 357:1821–1828.

6. El Khaldi M, Pernter P, Ferro F, Alfieri A, Decaminada N, Naibo L, et al. Detection of cerebral aneurysms in nontraumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage: role of multislice CT angiography in 130 consecutive patients. Radiol Med. 2007. 112:123–137.

7. Eggert SM, Eggers KA. Subarachnoid haemorrhage following spinal anaesthesia in an obstetric patient. Br J Anaesth. 2001. 86:442–444.

8. Sherer DM, Onyeije CI, Yun E. Pneumocephalus following inadvertent intrathecal puncture during epidural anesthesia: a case report and review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Med. 1999. 8:138–140.

9. Böttiger BW, Diezel G. [Acute intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage following repeated spinal anesthesia]. Anaesthesist. 1992. 41:152–157.

10. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003. 26:Suppl 1. S5–S20.

11. Banerji MA, Lebovitz HE. Insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant variants in NIDDM. Diabetes. 1989. 38:784–792.

12. Priebe HJ. Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage and the anaesthetist. Br J Anaesth. 2007. 99:102–118.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download