Abstract

Type B lactic acidosis is a rare condition in patients with solid tumors or hematological malignancies. Although there have been several theories to explain its mechanism, the exact cause of lactic acidosis remains to be discovered. Lactic acidosis is usually related to increased tumor burden in patients with malignancy. We experienced a case of lactic acidosis in a 39-year-old man who visited an emergency room because of dyspnea, and the cause of lactic acidosis turned out to be recurrent acute leukemia. Chemotherapy relieved the degree of lactic acidosis initially, but as the disease progressed, lactic acidosis became aggravated. Type B lactic acidosis can be a clinical presentation of acute exacerbation of acute leukemia.

Lactic acidosis is one of the metabolic acidoses with increased anion gap. Lactic acidosis is defined as pH ≤ 7.35 and plasma lactate concentration ≥ 5 meq/L.1 There are two types of lactic acidosis. Type B occurs in malignancy, diabetes mellitus, renal or hepatic failure, severe infection, and drugs, whereas type A is caused by apparent tissue ischemia, as in shock, severe anemia, mitochondrial enzyme defects, and inhibitors such as carbon monoxide and cyanide.2 Lactic acidosis is a rare and often overlooked condition, but is associated with high mortality, because of advanced disease process and high tumor burden. We report a case of a 39-year-old man with recurred leukemia who presented with lactic acidosis.

A 39-year-old man visited an emergency room because of dyspnea for 1 week. Seventeen years prior to admission, he was diagnosed with acute lymphoid leukemia in another hospital. One year ago, he was admitted to this hospital with general weakness, and a bone marrow biopsy showed leukemia recurrence. The bone marrow biopsy revealed acute pre-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), group II with aberrant expression of CD33. Upon fluorescence in situ hybridization, p16 (CEP9) deletion on chromosome 9p21 was detected. After reinduction chemotherapy with vincristine, prednisolone, daunorubicin, and L-asparaginase (VPDL), he achieved a hematological but not a cytogenetic response. Upon admission, no specific sign was present except tachypnea, (respiratory rate 36 breaths/min). Blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg, pulse rate was 100 bpm, and body temperature was 36.9℃. No hepatomegaly was noted.

Laboratory data showed pH 7.206, PaCO2 11.7 mmHg, PaO2 131.3 mmHg, bicarbonate 4.5 mmol/L, and base excess -21.1. Serum sodium was 133 mEq/L, potassium 4.1 mEq/L, chloride 102 mEq/L, and the anion gap was 19.3 mEq/L. The complete blood cell count showed a white blood cell of 3,200/µL, hemoglobin 9.6 g/dL, and platelet count of 83,000/µL. The differential count showed 61% neutrophils, 27% lymphocytes, 11% immature cells, 1% band neutrophils, and no basophils, eosinophils or monocytes. The coagulation profile was within the normal range. Blood chemistry showed 17 mg/dL blood urea nitrogen, 0.8 mg/dL creatinine, 4.5 g/dL albumin, 8 IU/L aspartate aminotransferase, 5 IU/L alanine aminotransferase, 0.67 mg/dL total bilirubin, and 302 IU/L lactate dehydrogenase. C-reactive protein was 1.34 mg/dL. The random plasma glucose level in the emergency room was 179 mg/dL. Peripheral blood morphology examination showed 20% blasts with some spherocytes and tear drop cells. Serum thiamine level was 18.60 ng/mL (normal range, 21.3-81.9 ng/mL). A chest radiography showed no active infiltrative lesions.

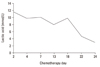

Continuous bicarbonate replacement therapy was performed to maintain cardiovascular stability. Arterial blood gas analysis improved to pH 7.346, PaCO2 20.1 mmHg, PaO2 135.2 mmHg, H CO3- 10.7 mmol/L, and base excess of -12.3 mmol/L. The blood lactate level was not checked in the emergency room. On day 3 of admission, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, and the result showed that ALL was sustained. Re-induction chemotherapy with vincristine and prednisone (VP) regimen was started immediately. Lactate was 11.6 mmol/L on day 2 of chemotherapy. After 3 weeks, lactate level decreased to 4.6 mmol/L.

After finishing the chemotherapeutic schedule, leukemic blasts still showed on the follow-up bone marrow examination, and the number and percentage of blast cells in the peripheral blood started to increase. As the number of immature cells in peripheral blood increased, the lactic acid began to increase again. The serum lactic acid level fluctuated from 12 to 20 mmol/L, regardless of bicarbonate replacement. However, the patient was asymptomatic and blood pH remained neutral without bicarbonate replacement therapy. On day 147 of admission, the patient expired as a result of disease progression combined with uncontrolled infection (Fig. 1).

Lactic acid is a degradation product of glucose in anaerobic conditions. After glycolysis, pyruvate is converted to acetylcoenzyme A (CoA) to form energy in the Krebs cycle in aerobic conditions. However, in anaerobic conditions, pyruvate is converted to lactate. Lactate is normally formed in skeletal muscle, red blood cells, and the brain, and its amount is usually less than 1,500 mmol/day. It is metabolized to form water and carbon dioxide in liver and kidneys. Lactic acidosis results from an imbalance of formation and degradation of lactic acid.3

More frequent causes of lactic acidosis in patients with malignancy are heart failure, sepsis, and decreased effective circulating volume, and these result in type A lactic acidosis. Type B lactic acidosis in malignancy was first reported in 1963, in an acute leukemia patient.4 In Korea, a case of lactic acidosis in a patient with leukemia transformed from lymphoma was reported in 1999,5 and a case of lactic acidosis due to thiamine deficiency was reported in 2007.6

The present case did not have any signs of infection, hypoxia, or circulatory failure. The mechanism of type B lactic acidosis in malignancy is unidentified, but it may be caused by tumor microembolism, increased glycolysis, and decreased gluconeogenesis by abnormal tumor metabolism, or decreased degradation of lactic acid because of extensive liver involvement. Tumor necrosis factor-α is thought to play a role by reducing the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase, which converts pyruvate to acetyl-CoA.7 It also inhibits the cytochrome-dependent electron transport system and increases anaerobic glycolysis.7 Lactic acid is metabolized mainly in the liver and kidneys. The liver contributes to 90% of lactate metabolism and is frequently involved in patients with lactic acidosis.8-10 In the present case, there was no evidence of liver involvement. Thiamine deficiency is also known to be a cause of lactic acidosis,11 but this patient was refractory to thiamine replacement.

Treatment of the primary condition, such as chemotherapy in malignancy, remains the mainstay of treatment.1 Treatment with renal replacement therapy is controversial. In 2001, Sillos, et al.1 reported a case of lactic acidosis in an 11-year-old girl with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood pH improved rapidly after continuous veno-venous hemofiltration, but her plasma lactate concentration continued to increase. It decreased after chemotherapy began to take effect.

In patients with metabolic acidosis of unknown origin, lactic acidosis should be considered. Serum lactic acid levels should be checked in cases of metabolic acidosis with increased anion gap. Leukemia usually presents as a fever, infection, and bleeding tendency, with lactic acidosis as a rare presentation. Physicians should be aware of lactic acidosis in recurring or advanced malignancy, and treatment of the underlying disease should be performed immediately.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Sillos EM, Shenep JL, Burghen GA, Pui CH, Behm FG, Sandlund JT. Lactic acidosis: a metabolic complication of hematologic malignancies: case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 2001. 92:2237–2246.

2. Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson JL, Fauci AS. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 2004. 16th ed. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc..

3. Woops HF. Some aspects of lactic acidosis. Br J Hosp Med. 1971. 6:666–676.

4. Scheerer PP, Pierre RV, Schwartz DL, Linman JW. Reed-Sternberg-cell leukemia and lactic acidosis; unusual manifestations of Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med. 1964. 270:274–278.

5. Ma KA, Seo YJ, Kim SJ, Ahn SK, Kim MS, Chung HJ, et al. Lactic acidosis associated with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Korean J Nephrol. 1999. 18:505–509.

6. Byun SW, Choi SH, Park HG, Kim BJ, Kim EY, Lee KH, et al. A case of lactic acidosis caused by thiamine deficiency. Korean J Med. 2007. 73:443–447.

7. Friedenberg AS, Brandoff DE, Schiffman FJ. Type B lactic acidosis as a severe metabolic complication in lymphoma and leukemia: a case series from a single institution and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007. 87:225–232.

8. Block JB. Lactic acidosis in malignancy and observations on its possible pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974. 230:94–102.

9. Weber G. Enzymology of cancer cells (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1977. 296:541–551.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download