Abstract

Bortezomib, an inhibitor of 26S proteosome, is recently approved treatment option for multiple myeloma. Thalidomide, a drug with immunomodulating and antiangiogenic effects, has also shown promise as an effective treatment in multiple myeloma. Pulmonary complications are believed to be rare, especially interstitial lung disease. Here, we describe a patient with dyspnea and diffuse pulmonary infiltrates while receiving bortezomib and thalidomide in combination with dexamethasone for treatment-naïve multiple myeloma. Bronchoalveolar lavage demonstrated a significant decrease in the ratio of CD4 : CD8 T lymphocytes (CD4/8 ratio, 0.54). Extensive workup for other causes, including infections, was negative. A lung biopsy under video-assisted thorascopic surgery revealed a diagnosis of nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis. The symptoms and imaging study findings improved after initiating steroid treatment. Physicians should be aware of this potential complication in patients receiving the novel molecular-targeted antineoplastic agents, bortezomib and thalidomide, who present with dyspnea and new pulmonary infiltrates and fail to improve despite treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Treatments of multiple myeloma have significantly changed with improved understanding of potential myeloma targets and have led to the era of novel molecular-targeted antineoplastic agents, such as bortezomib and thalidomide.1 Bortezomib, an inhibitor of 26S proteosome, is a recently approved treatment option for multiple myeloma.2 Thalidomide, a drug with immunomodulating and antiangiogenic effects, along with anticytokine activity, has also shown promise as an effective treatment in multiple myeloma. As novel treatments of multiple myeloma become more frequent, physicians must be aware of the possible toxicities. The reported common adverse effects of bortezomib and thalidomide are asthenic conditions, gastrointestinal disturbances, and peripheral neuropathy.3 Pulmonary complications are believed to be uncommon, and interstitial lung disease (ILD) is very rare.4 In this report, we describe a patient receiving bortezomib and thalidomide in combination with dexamethasone for treatment-naïve multiple myeloma in whom dyspnea and new pulmonary infiltrates developed, and whose workup revealed a diagnosis of histologically-confirmed nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis (NSIP).

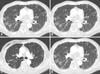

A 67-year-old man was admitted because of back pain caused by the compression fracture of the lumbar spines. Serologic tests and bone marrow studies confirmed the pathologic diagnosis of multiple myeloma, immunoglobulin G (IgG) type. After he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma at another hospital, he was referred to our hospital for chemotherapy. In this frontline setting, a bortezomib-based combination regimen was employed, consisting of bortezomib administration at 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, thalidomide at 100 mg/day, and dexamethasone at 40 mg on days 1-4 and 8-11. After the completion of the first 3-week cycle, he complained of mild dyspnea. He was afebrile. A physical examination revealed fine crackles in the bilateral upper lung fields. Room air arterial blood gas analysis showed respiratory alkalosis (PaO2, 113 mmHg; PaCO2, 19 mmHg). His chest radiograph showed mild interstitial and reticular opacities in both lungs, and a high resolution chest CT demonstrated newly developed subpleural reticulation and diffuse interstitial changes in both the upper and mid-lungs with a ground glass appearance (Fig. 1A and B). Although lung complications are not common with the use of the novel antineoplastic agents, treatment with the second cycle was discontinued on day 7 for possible drug-induced interstitial pneumonitis. Simultaneously, broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered because of his immunocompromised status.

Results of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) showed a significantly decreased ratio of CD4 : CD8 T lymphocytes (CD4/8 ratio, 0.54), and transbronchial lung biopsy showed mild interstitial fibrosis. A microbial culture obtained from BAL provided no evidence of bacterial, viral, or fungal pathogens. Subsequently, wedge resection of the upper and middle lobes of the right lung was carried on under video-assisted thoraco-scopic surgery (VATS), and he was diagnosed as NSIP (Fig. 2). Within six weeks of steroid treatment, follow-up chest radiographs and high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) revealed marked improvement of interstitial pneumonitis (Fig. 1C and D). The steroid treatment was effective and its dosage was decreased according to the tapering schedule at the time of discharge.

Previous clinical studies on bortezomib and thalidomide have shown low incidences of pulmonary adverse effects,4 and few cases of severe pulmonary toxicity associated with bortezomib and thalidomide have been reported.

ILD induced by bortezomib and thalidomide is very rare. Only one case of thalidomide-induced interstitial pneumonitis5 and one case of bortezomib-induced interstitial pneumonitis have been reported so far.6 None of the previous two ILD cases were confirmed by biopsy, thus the subtype is not known. Our case is therefore the first case of histologically-confirmed NSIP associated with bortezomib and thalidomide during multiple myeloma treatment.

The mechanism of pulmonary toxicity associated with bortezomib and thalidomide is unclear. Although the precise mechanism of action of thalidomide is still uncertain, together with its antiangiogenic activity, it appears to have immunomodulatory and anticytokine effect and alter the production and activity of cytokines. Since it is postulated that bortezomib affects not only nuclear factor (NF)-kB activity but also various signaling pathways, its metabolites might cause cellular reactions associated with pulmonary injuries in some patients.7 In vitro studies with human liver microsomes indicate that bortezomib is primarily oxidatively metabolized through the cytochrome P450 family of enzymes. Although the biotransformation occurs predominantly in the liver, the lung may be a site of active drug metabolism as well, for the lung has cytochrome P450 enzymes levels estimated at 10 to 15 percent of that of the liver, including the lung-specific cytochrome P450 enzymes. When bortezomib and thalidomide are used together, the adverse effects might synergize and result in severe pulmonary toxicity such as ILD.

In conclusion, we present the first case of histologically-confirmed NSIP after the administration of bortezomib and thalidomide. Physicians should be aware of this potential complication in patients receiving the novel targeted antineoplastic agents, bortezomib and thalidomide, who present with dyspnea and new pulmonary infiltrates and fail to improve despite treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Chest CT scans. (A and B) After the first cycle of triple regimen, at the time of clinical deterioration demonstrating newly developed subpleural reticulation and diffuse interstitial changes in both upper and mid-lungs with a ground glass appearance. (C and D) Six weeks after initiating the steroid treatment with marked improvement of interstitial pneumonitis. |

| Fig. 2Video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy photomicrographs (Hematoxylin Eosin staining). (A) Alveolar walls are thickened with diffuse interstitial fibrosis (original magnification ×12). (B) Interstitial fibrosis with characteristic temporal monogeneity is present with associated chronic interstitial inflammation, whereas fibroblastic foci are not seen (original magnification ×100). |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine for 2005 (6-2005-0054).

References

1. Ghobrial IM, Leleu X, Hatjiharissi E, Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Schlossman R, et al. Emerging drugs in multiple myeloma. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007. 12:155–163.

2. Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Anderson KC. The emerging role of novel therapies for the treatment of relapsed myeloma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007. 5:149–162.

3. Colson K, Doss DS, Swift R, Tariman J, Thomas TE. Bortezomib, a newly approved proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma: nursing implications. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2004. 8:473–480.

4. Dimopoulou I, Bamias A, Lyberopoulos P, Dimopoulos MA. Pulmonary toxicity from novel antineoplastic agents. Ann Oncol. 2006. 17:372–379.

5. Onozawa M, Hashino S, Sogabe S, Haneda M, Horimoto H, Izumiyama K, et al. Side effects and good effects from new chemotherapeutic agents. Case 2. Thalidomide-induced interstitial pneumonitis. J Clin Oncol. 2005. 23:2425–2426.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download