Abstract

Rectal syphilis, known as a great masquerader, can be difficult to diagnose because of its variable symptoms. Gastroenterologists should be aware of the possibility of rectal syphilis when confronted with anorectal ulcers, and should gather a detailed history about sexual preferences and practices, including homosexuality. We report a case of primary rectal syphilis mimicking rectal cancer on radiologic imaging. In this report, we described the clinical, endoscopic, and radiologic features of this rare case.

In recent years, risky sexual behaviors with regard to sexually transmitted diseases have increased, particularly unprotected anal intercourse.1 Consequently, sexually transmitted diseases should be considered in patients with rectal symptoms and a history of anal intercourse, and the possibility of rectal syphilis should also be considered because the incidence of syphilis has risen over the last few years.2 Physicians should be aware of the various manifestations of this rare disease in order to avoid incorrect diagnosis, inappropriate treatment, and delayed antibiotic therapy.3-5 In this paper, we describe a case of primary rectal syphilis that was suspected to be a rectal cancer.

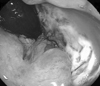

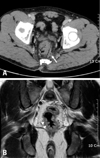

A 45-year-old man was referred to our hospital for suspected rectal cancer. He complained of anal pain with tenesmus, mucoid discharge, and intermittent presence of blood in stool. On physical examination, he revealed 1-cm-sized firm, non-tender lymphadenopathies in both inguinal areas. No gross abnormality was observed around the anus, but an ulcerative indurated mass was palpable in the right lateral side of the antorectum on a digital rectal examination. Laboratory investigation showed leukocytosis of 11.3×106/mL (normal range, 4.0-10.0×106/mL) and elevated C-reactive protein of 7.06 mg/L (normal range, 0.0-5.0 mg/L). Routine blood chemistry and serum carcinoembryonic antigen were within normal limits. Sigmoidoscopy showed a 3×4 cm sized welldemarcated, deep ulcer that was not typical of a carcinoma on the lower rectum extending from the anal canal (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis suggested rectal cancer by revealing irregular rectal wall thickening with multiple perirectal lymph node enlargements (Fig. 2A). Coronal magnetic resonance imaging revealed wall thickening of the distal rectum in the mucosa and submucosa layer with high signal intensity and perirectal fat infiltration in T2-weighted images (Fig. 2B). Histological findings of an endoscoic biopsy showed diffuse chronic inflammatory cell infiltration predominantly composed of plasma cells, an absence of atypia or neoplastic changes, and multiple spiral rods consistent with spirochetes on a Warthin-Starry stain (Fig. 3). Further questioning revealed an episode of rectal intercourse dating 2 months before the onset of the symptoms. An automated rapid plasma reagent test (Sekisui Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was positive with 40 units (normal range: < 1 unit) and a Treponema pallidum latex agglutination test (Sekisui Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was reactive with 2,100 TPLA units (normal range: < 10 unit). A human immunodeficiency virus antibody test was negative. Based on the pathologic and serologic findings, we made a diagnosis of primary rectal syphilis. The patient was treated with one dose of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine of 2.4 million units, and a single dose of penicillin therapy induced rapid regression of the rectal ulcer. Follow-up sigmoidoscopy after 3 months showed complete regression of the chancre, and a follow-up rapid plasma reagent test was negative.

People presenting with anorectal lesions may need to have a sexual history taken to establish whether anorectal intercourse has taken place.6 Although primary rectal syphilis is very rare, physicians should keep the possibility of rectal syphilis in mind because the prevalence of syphilis has risen over the last few years.7 A sexual history is important, but homosexual males may have the tendency to conceal their sexual histories from physicians. The patient in the present case also did not indicate homosexuality in the initial clinical history, and further careful questioning was necessary to prompt him to admit to passive anal intercourse. A sexual history may be unreliable and specific inquiries should be made regarding anal intercourse whenever an unusual anorectal lesion is noted.

Rectal syphilis is often missed because it is usually asymptomatic or causes only mild symptoms.8 However, instances of rectal syphilis extending between the anal verge and dentate line, as in the present case, tend to be extremely painful.9 Rectal syphilis is one of the great masqueraders due to its variable symptoms including itching, bleeding, tenesmus, urgency of defecation, and anal discharge, which may be purulent, mucoid, or blood stained.2,6,10,11 Therefore, physicians should be aware of its various manifestations to avoid inappropriate treatments.3,4

The dark-field microscopy may constitute the initial diagnostic maneuvers, however, dark-field microscopy of exudates from a rectal ulcer may be inaccurate because of contamination from commensal spirochetes found in the normal flora of the rectum. In our case, a dark-field examination was not performed due to these reasons. The diagnosis of rectal syphilis is based primarily on serology and an endoscopic biopsy of anorectal lesions.12,13 The spectrum of endoscopic findings of rectal syphilis appears to be very diverse and includes proctitis, masses, ulcers, and pseudotumors.10,14 The differential diagnosis should include inflammatory bowel disease, proctitis of another etiology, solitary rectal ulcer, chancroid, viral anorectal ulcers (herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus), lymphomas, lymphogranuloma venereum, and rectal cancer.14-17 Ulcers of rectal syphilis may be eccentrically located, multiple, or irregular, and two ulcers may be opposite each other in a "kissing" configuration.18 Therefore, any anorectal ulcer that is not typical of carcinoma or other conditions should be viewed with suspicion. Endoscopists should perform multiple biopsies because standard histological evaluation may occasionally be nonspecific.16,19 The yield from conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining is known to be low, and Warthin-Starry staining, which is known to be specific for syphilis, is usually required to identify spirochetes. The initial treatment of patients with rectal syphilis is a single dose of benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units in one intramuscular injection as in our case; however, patients with long-standing diseases may require this dose repeated at weekly intervals for three weeks.17,20 Careful serologic and rectal reexaminations at regular intervals are necessary to document eradication of the infection.

In conclusion, patients with rectal syphilis may undergo unnecessary investigations if a detailed history about their sexual preferences and practices are not asked. The possibility of rectal syphilis should be included in the differential diagnosis of an anorectal ulcer whenever the ulcer is not typical of carcinoma or other conditions.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Sigmoidoscopic findings indicated a large, well-demarcated ulcer that was not typical of carcinoma on the lower rectum. |

| Fig. 2Radiologic findings of rectal syphilis. (A) CT of the abdomen and pelvis suggested rectal cancer by revealing irregular rectal wall thickening with multiple perirectal lymph node enlargements (white arrow). (B) Coronal MRI showed wall thickening of the distal rectum in the mucosa and submucosa layer with high signal intensity (white arrowheads) and perirectal fat infiltration in T2-weighted images. |

| Fig. 3Histologic features of the rectal syphilis. (A) The rectal chancre showed diffuse chronic inflammatory cell infiltration predominantly composed of plasma cells in the lamina propria and some blood vessels (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200). (B) Large numbers of spirochetes (white arrows) were present on a special staining of the rectal biopsy specimen (Warthin-Starry stain, ×1,000). |

References

1. Elford J, Bolding G, Davis M, Sherr L, Hart G. Trends in sexual behaviour among London homosexual men 1998-2003: implications for HIV prevention and sexual health promotion. Sex Transm Infect. 2004. 80:451–454.

2. Bassi O, Cosa G, Colavolpe A, Argentieri R. Primary syphilis of the rectum--endoscopic and clinical features. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991. 34:1024–1026.

3. Quinn TC, Lukehart SA, Goodell S, Mkrtichian E, Schuffler MD, Holmes KK. Rectal mass caused by Treponema pallidum: confirmation by immunofluorescent staining. Gastroenterology. 1982. 82:135–139.

4. Drusin LM, Homan WP, Dineen P. The role of surgery in primary syphilis of the anus. Ann Surg. 1976. 184:65–67.

5. Hetch H. Venereal diseases in homosexuals. Acta Derm Venereol. 1957. 37:462–466.

6. Hamlyn E, Taylor C. Sexually transmitted proctitis. Postgrad Med J. 2006. 82:733–736.

7. Righarts AA, Simms I, Wallace L, Solomou M, Fenton KA. Syphilis surveillance and epidemiology in the United Kingdom. Euro Surveill. 2004. 9:21–25.

8. Hughes E, Cuthbertson AM, Killingback MK. Venereal diseases of the anal canal and rectum. Colorectal surgery. 1983. New York: Churchill Livingston;203–208.

9. Goligher JC. Sexually transmitted disease. Diseases of the anus, rectum, and colon. 1985. 5th ed. London: Balliere-Tindall;1033–1045.

11. Mindel A, Tovey SJ, Timmins DJ, Williams P. Primary and secondary syphilis, 20 years' experience. 2 Clinical features. Genitourin Med. 1989. 65:1–3.

12. Goh BT. Syphilis in adults. Sex Transm Infect. 2005. 81:448–452.

13. Larsen SA. Syphilis. Clin Lab Med. 1989. 9:545–557.

14. Le Marchant JM, Ferrand B. [Primary syphilitic proctitis associated with liver involvement (autor's transl)]. Sem Hop. 1981. 57:1434–1438.

15. McMillan A, Lee FD. Sigmoidoscopic and microscopic appearance of the rectal mucosa in homosexual men. Gut. 1981. 22:1035–1041.

16. Faris MR, Perry JJ, Westermeier TG, Redmond J 3rd. Rectal syphilis mimicking histiocytic lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983. 80:719–721.

18. Wexner SD. Sexually transmitted diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus. The challenge of the nineties. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990. 33:1048–1062.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download