Abstract

Purpose

We performed this study in order to evaluate the incidence and characteristics of urolithiasis in patients with malignant hematologic diseases.

Materials and Methods

Nine hundred one patients who underwent medical treatment for malignant hematologic disease and 40,543 patients who visited the emergency room and without malignant hematologic diseases were included in our study. The patients with malignant hematologic diseases were divided into two groups depending on their primary treatment. Group I included patients with acute and chronic leukemia (AML, ALL, CML, CLL) for which chemotherapy and steroid therapy was necessary, and group II included patients with anaplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome and who had undergone repeated transfusion for treatment. Comparisons were made between the two groups in respect to the incidence of urolithiasis and the stones' radiopacity.

Results

Twenty nine patients (3.2%) of the 901 malignant hematologic patients were diagnosed with urolithiasis, compared to 575 patients (1.4%) of 40,543 emergency room patients. There was a significant increase of the incidence of urolithiasis in the malignant hematologic group. Compared to the general patients, the patients with malignant hematologic diseases had a higher rate of radiolucent stones (46.6% versus 16.3%, respectively), and the difference was significant.

Urolithiasis is one of the most common urologic diseases, and its incidence and prevalence is generally reported between 0.1-0.3% and 5-10% in the general population.1 Although there is still debate regarding the causes of stone, the risk factors that are known to contribute to stone occurrence are Caucasian race, the male gender, a family history of urolithiasis, immobilization, urinary infection, glucocorticoid therapy, hypercalcemia, hyperuricuria, hyperoxaluria, hypocitria, etc.

The role of glucocorticoid is particularly striking in patients treated with consolidation chemotherapy for acute leukemia. Howard, et al.2 reported that the rate of urolithiasis was 4.5 times higher for patients during induction therapy and 2.2 times higher for patients during consolidation therapy using pulsatile glucocorticoids than that for patients who had completed therapy.

Despite anticipating a high incidence of stone due to the characteristic therapy for patients suffering from malignant hematologic diseases, there have been few studies on this in the English medical literature. Therefore, we performed this study to find incidences and characteristics of urolithiasis in patients with malignant hematologic diseases.

Nine hundred one patients from the Hematologic Department who received medical treatment for malignant hematologic diseases between July 2003 and June 2005 were included in our study, and 40,543 patients who visited the emergency room during that same period without malignant hematologic diseases were included in the control group.

Of the 901 evaluable patients with malignant hematologic diseases, the median age at the time of diagnosis was 46 years (age range: 20 to 67 years) and that of the 40,543 patients was 46 years (age range: 20 to 94 years). The ratio of male to female was 0.93 : 1 and 0.96 : 1 in the patients group and control group, respectively.

The patients with malignant hematologic diseases-were only enrolled after July 2003 and we excluded the patients with a history of urolithiasis before making the diagnosis of malignant hematologic diseases.

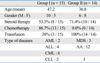

The patients with malignant hematologic diseases were divided into two groups depending on their main treatment: group I (n = 520) included acute and chronic leukemia which needed chemotherapy and glucocorticoid therapy, and group II (n = 379) included patients with anaplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome and who had undergone repeated blood transfusions for treatment. We investigated the presence of chemotherapy and glucocorticoid therapy, the number of blood transfusions, and the incidence rate of urolithiasis for each group. The diagnosis of urolithiasis was confirmed by excretory urography or abdominal computerized tomography (CT) for the patients who visited our department due to symptoms of urolithiasis-like flank pain and/or hematuria. Comparisons were made between the two groups with respect to the incidence of urolithiasis and the stones' nature by radiopacity through Plain film of the kidney, ureter, and bladder (KUB).

The patients were retrospectively identified by a computer-assisted review of the medical charts and by using an image recording system. Fisher's exact test was used to analyze the data for statistics. p values < 0.05 were regarded as significant.

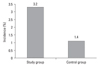

Twenty nine (3.2%) of the 901 patients with malignant hematologic diseases were diagnosed with urolithiasis, compared to 575 (1.4%) of the 40,543 general patients who visited the emergency room. The incidence of urolithiasis of the malignant hematologic group significantly increased (p = 0.043) (Fig. 1). The incidence of urolithiasis in group I and group II was 2.9% (15/520) and 3.7% (14/381), respectively. Although the latter was higher than the former, there was no significant difference (p = 0.181)

The median age of the 29 patients who were confirmed with urolithiasis and malignant hematologic diseases was 45.3 years (range: 21 years-66 years), and the gender ratio (male : female) was 1.14 to 1 (Table 1). The size of the stones was 4.3 ± 0.8 mm. The most common site was the upper ureter (41.4%, 12/29) and the main symptoms were flank pain and gross hematuria 43.3% and 36.6%, respectively (Table 2). The initial therapy for urolithiasis in the group of general patients was electric shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or ureteroscopic lithotripsy [64.0% (345/575)], while that in the group of malignant hematologic diseases was conservative therapy [55.2% (16/29)], ESWL [37.9% (11/29)] and ureteroscopic lithotripsy [6.8% (2/29)].

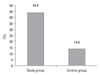

Compared to the general patients, the patients with malignant hematologic diseases had a higher rate of radiolucent stones [44.8% (13/29) versus 14.9% (86/575)], and the difference was significant (p = 0.022) (Fig. 2).

Howard, et al.2 reported in their study, which spanned 30 years and included over 20,000 person-years of follow-up that urolithiasis occurred in 0.9% of the pediatric acute lymphatic leukemia patients, and the incidence was much higher than otherwise healthy children and adolescents. In our study, the prevalence rate of urolithiasis for the patients with malignant hemotologic diseases was 3.2% compared to 1.4% for the general patients, and the rate was statistically higher than that for the general patients. This incidence rate of stone was much higher than that Hesse A, et al.4 and Curhan, et al.4 reported (0.3-0.5%) for the general population in Western countries, and it was also higher than that reported by Kim, et al.5 (0.2%) for Koreans.

We think that these differences are associated with the therapeutic methods that were used for the patients in different studies. The basis of treatment for malignant hematologic diseases are chemotherapy and maintenance therapy by glucocorticoid. Sixteen of the patients who had urolithiasis had undergone chemotherapy more than once and nine of them were given additional treatments for maintenance therapy by glucocorticoid. It is presumed that chemotherapy is a risk factor for urolithiasis due to tumorlysis syndrome that often occurs during chemotherapy of patients with malignant hematologic diseases, and tumorlysis syndrome after chemotherapy often causes an increased concentration of uric acid in the serum by the increasing cell damage and hemolysis.6

Glucocortcoid is widely used as maintenance therapy for the treatment of patients with leukemia because it decreases the leukemic blast cell count and the rate of extramedullary infiltration.7 However, glucocorticoid therapy over a long period affects the metabolic pathway of calcium, and then it induces decreased absorption of calcium in the gastrointestinal tract and increased excretion of calcium in the urine. All of these problems can lead to urinary stone disease. Almost all the patients in the aplastic anemia and myeloplastic syndrome groups, which had a relatively higher incidence rate of urolithiasis, underwent repeated blood transfusions for symptom relief. This incidence rate was 64% of those patients who underwent blood transfusion 20 times before the diagnosis of urolithiasis.

Most of patients with malignant hematologic diseases have compromised immunity. They are susceptible to urinary tract infection and renal dysfunction owing to urinary obstruction. Therefore, the occurrence of urolithiasis in these patients is more morbid and complicated compared to general patients. Yet the urolithiais of these patients can be misdiagnosed as other diseases like gastritis, cholecystitis or hemorrhagic cystitis. Pui, et al.10 reported in their study that they enrolled 2,457 patients with acute leukemia to investigate urinary stone and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and they confirmed urinary stones in only five of their patients (0.2%, 5/2457). They explained that it is possible that the urologic symptoms of urolithiasis, like flank pain and abdominal discomfort, were mistaken for neuropathy that was caused by chemotherapy or for gastritis that was caused by glucocorticoid therapy. Jaing, et al.11 asserted that when patients with acute leukemia were diagnosed as staghorn calculi, it was important to distinguish urolithiasis from hemorrhagic cystitis due to the side effects of chemotherapy, and attention should be paid to the similarity of the symptoms.

In our study, we have some limitations for diagnosis because we surveyed patients who consulted our clinic for symptoms that were suspicious of urolithiasis. Therefore, it is possible that symptoms of urolithiasis were in fact neglected or mistaken for those seeming side effects of chemotherapy given in other departments. We did not perform an analysis of urolithiasis in our study, therefore we cannot confirm the accurate composition of the stones. However, the most basic test to diagnose urinary stones is a simple X-ray of the KUB, and the level of radiopacity on KUB enables us to infer the composition of urinary stones indirectly.12 The total ratio of radiolucent stones in patients with hematologic diseases was much higher than that for general patients. Yet the control group was limited to patients with confirmed urolithiasis and who visited the emergency room. So this cannot completely represent the general population.

ESWL is inadequate to completely remove stones in the group of patients with malignant hematologic diseases because of the existence of radiolucent stones or hematologic abnormalities, and many cases were unsuitable for invasive ureteroscopic lithotripsy due to the chemotherapy patients were receiving or their generally poor condition.

Further studies on the risk factors associated with the incidence of urolithiasis, the electrolyte levels of serum or urine, and an analysis of the composition of urinary stones need to be done in the near future.

In conclusion, the incidence rate of urolithiasis and radiolucent stone in the group of patients with malignant hematologic diseases was higher than that in the group of general patients. We cannot definitely find out the pathophysiology of the stone in this study. However, close attention should be paid to the possibility of misdiagnosing urolithiasis because of the treatment side effects for malignant hematologic diseases.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Comparison of the stone incidence in the study group and the control group. Study group: patients of malignant hematologic disease, Control group: patients who visited the emergency room (p = 0.04). |

| Fig. 2Comparison of the incidence of radiolucent stones between control and study group. Study group: patients of malignant hematologic disease. Control group: patients who visited the emergency room (p = 0.02). |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Presented in Joint Annual Meeting of American Urological Association, Anaheim, California (19-24 May 2007)

References

1. Leusmann DB, Blaschke R, Schmandt W. Results of 5,035 stone analyses: a contribution to epidemiology of urinary stone disease. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1990. 24:205–210.

2. Howard SC, Kaplan SD, Razzouk BI, Rivera GK, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro RC, et al. Urolithiasis in pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2003. 17:541–546.

3. Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ. A prospective study of dietary calcium and other nutrients and the risk of symptomatic kidney stones. N Engl J Med. 1993. 328:833–838.

4. Hesse A, Siener R. Current aspects of epidemiology and nutrition in urinary stone disease. World J Urol. 1997. 15:165–171.

5. Kim SC, Moon YT, Hong YP, Hwang TG, Choi SH, Kim KJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of urinary stones in Koreans. J Korean Med Sci. 1998. 13:138–146.

6. Jabbour E, Ribrag V. [Acute tumor lysis syndrome: update on therapy.]. Rev Med Interne. 2005. 26:27–32.

7. Hiçsönmez G. The effect of steroid on myeloid leukemic cells: the potential of short-course high-dose methylprednisolone treatment in inducing differentiation, apoptosis and in stimulating myelopoiesis. Leuk Res. 2006. 30:60–68.

8. Rubin MR, Bilezikian JP. Clinical review 151: The role of parathyroid hormone in the pathogenesis of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: a re-examination of the evidence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002. 87:4033–4041.

9. Bolan CD, Greer SE, Cecco SA, Oblitas JM, Rehak NN, Leitman SF. Comprehensive analysis of citrate effects during plateletpheresis in normal donors. Transfusion. 2001. 41:1165–1171.

10. Pui CH, Roy S 3rd, Noe HN. Urolithiasis in childhood acute leukemia and nonHodgkin's lymphoma. J Urol. 1986. 136:1052–1054.

11. Jaing TH, Hung IJ, Lin CJ, Chiu CH, Luo CC, Wang CJ. Acute myeloid leukemia complicated with staghorn calculus. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002. 32:365–367.

12. Pietrow PK, Preminger GM. Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Evaluation and medical management of urinary lithiasis. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 2007. Philadelphia: Saunders;1393–1430.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download