Abstract

Purpose

This study examined the association between early initiation of problem behaviors (alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse) and suicidal behaviors (suicidal ideation and suicide attempts), and explored the effect of concurrent participation in these problem behaviors on suicidal behaviors among Korean adolescent males and females.

Materials and Methods

Data were obtained from the 2006 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey, a nationally representative sample of middle and high school students (32,417 males and 31,467 females) in grades seven through twelve. Bivariate and multivariate logistic analyses were conducted. Several important covariates, such as age, family living structure, household economic status, academic performance, current alcohol drinking, current cigarette smoking, current butane gas or glue sniffing, perceived body weight, unhealthy weight control behaviors, subjective sleep evaluation, and depressed mood were included in the analyses.

Results

Both male and female preteen initiators of each problem behavior were at greater risk for suicidal behaviors than non-initiators, even after controlling for covariates. More numerous concurrent problematic behaviors were correlated with greater likelihood of seriously considering or attempting suicide among both males and females. This pattern was more clearly observed in preteen than in teen initiators although the former and latter were engaged in the same frequency of problem behavior.

Conclusion

Early initiation of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse, particularly among preteens, represented an important predictor of later suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in both genders. Thus, early preventive intervention programs should be developed and may reduce the potential risks for subsequent suicidal behaviors.

Since the economic crisis, suicide mortality has risen sharply among Korean adolescents aged 15 to 19 years (i.e., an increase of 40.7% from 5.4 per 100,000 in 2001 to 7.6 per 100,000 in 2005) and is the second leading cause of death among this population.1 Suicide and suicidal behaviors (suicidal ideation and suicide attempts) among adolescents have become major public health concerns in Korea, and it is thus important to determine the risk factors associated with such behaviors. In recent years, early age of onset of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse (i.e., during childhood) have been identified as important predictors, beyond the multiple risk factors in adolescence previously noted in the literature,2-5 of later suicidal behaviors (during adolescence).6-13 With the exception of alcohol drinking, which is usually measured by self-reported age at first alcoholic drink excluding those imbibed for religious reasons,10,12,13 age at initiation of cigarette smoking and sexual intercourse has been conservatively measured in most previous studies (i.e., "regular/daily smoking or smoking a whole cigarette" and "unwanted/forced sexual intercourse").7,8,14 By using such methodologies, previous studies may have overestimated the contribution of early initiation of cigarette smoking and/or sexual intercourse to suicidal behaviors. Furthermore, according to Jessor's Problem Behavior Theory,15 alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse have been highly correlated, even occurring simultaneously in some cases. Kim16 and Schmid, et al.17 reported that concur-rent users of alcohol and cigarettes were at higher risk for developing other problem behaviors (e.g., leaving home, delinquency, violating school rules) and substance use (e.g., stimulants/sleeping pills, marijuana, or butane gas/glue), compared to drinkers who did not smoke, smokers who did not drink, and abstainers (neither drinking nor smoking). However, little is known about the nature and extent of the health effects of early concurrent participation in problem behaviors, particularly in regard to later suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

According to the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, the average reported age of drinking and smoking initiation decreased from 15.1 and 15.0 years in 1998 to 13.1 and 12.5 years in 2006, respectively; the prevalence of adolescent female smokers (12.8%) was about twice as high as that of adult female smokers (5.6%); and age at first experience of sexual intercourse also decreased.16,18 These findings have prompted an increased interest in the subsequent psychological status of such individuals. Nonetheless, despite the numerous factors placing this population at higher risk for problematic and suicidal behaviors, relatively few studies have been conducted in this domain.

Therefore, this study examined the associations between early initiation of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking and sexual intercourse with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. This study also determined the effects on each outcome of concurrent engagement in these problem behaviors, controlling for various confounding factors.

Data were derived from the 2006 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBWS) conducted by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) to monitor the prevalence of high-risk behaviors. This study applied a stratified three-stage clustering design to produce a nationally representative sample of public and private middle and high school students in grades seven through twelve in all regions of Korea. The first stage involved 234 cities and districts with similar characteristics in regard to the degree of geographic accessibility; numbers of schools and residents, and employment rate in general and in the farming, mining, and service industries in particular. In the second stage, 400 middle schools and 400 high schools were selected from within the 234 cities and districts. The third stage of sampling consisted of randomly selecting one class from each grade within each chosen school. All students in selected classes were eligible to participate. The survey proceeded as follows: during July, school teachers were trained to assist students with participating in the survey; during August, the KCDC informed each school about the schedule for conducting the survey and provided certificate numbers for each student; during September and October, students used their certificate numbers to access and complete questionnaires during a regular class period. The KYRBWS was officially approved by the Korea National Statistical Office (KNSO Certificate Number: 11758). Further details regarding the survey design and methods have been provided elsewhere.18

From an original pool of 78,593 potential participants, 71,404 students were interviewed (response rate: 90.9%). However, data obtained from 7,520 (10.5%) respondents were omitted from the analysis due to missing information in regard to important questions (e.g., alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse). Consequently, data obtained from 63,884 adolescents (32,417 males and 31,467 females) were available for analysis (age range: 13-19 years; mean age: 16.2 ± 1.7 years for both genders).

This study used two outcome variables: suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Participants were asked whether they had seriously considered attempting suicide and/or had made a suicide attempt during the past 12 months. Responses were divided into yes/no categories for each question.

The primary variables of interest in this study involved three potentially problematic behaviors: alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse. Participants provided information about when, if ever, they had initiated each of these behaviors using a 14-point scale including never, preschool, and first to twelfth grades. Responses were recoded into three categories: teen initiators (seventh to twelfth grades), preteen initiators (first to sixth grades or preschool), and non-initiators. School grade appeared to serve as a more salient cue than age in terms of eliciting recollections from students.9 To test our second hypothesis, nine different categories were derived, according to the period at first occurrence, from the combination of the three problem behaviors, as shown in Table 5. For example, "teen initiators with one behavior" referred to individuals who initially experienced one of the three problem behaviors during their teenage years; "preteen and teen initiators with two behaviors" referred to individuals who initially experienced one of the three behaviors during their teenage years and one of the other behaviors during their preteen years.

Categorizations of several important covariates, such as age (in years); family living structure (living with both parents or living with a single parent/others); household economic status (low, middle, and upper); academic performance (low, middle, and upper); perceived body weight (underweight, about right, and overweight); subjective sleep evaluation (satisfaction or dissatisfaction), and depressed mood ("yes" if they had felt so sad or hopeless almost every day for 2 weeks or more in a row that you stop doing some usual activities during the past 12 months) were conventionally defined and straightforward, as shown in Table 2.19 We also included current alcohol drinking ("yes" if they had consumed alcohol one or more days during the past 30 days), current cigarette smoking ("yes" if they had smoked at least one cigarette during the past 30 days), current butane gas or glue sniffing ("yes" if they often or sometimes sniffed butane gas or glue), and current unhealthy weight control behaviors ("yes" if they had participated in any of the following behaviors during the past 30 days: fasting for 12 hours or more; eating less; taking diet pills, laxatives, or diuretics; vomiting; and eating only one food) in the analyses to test whether early engagement in each problem behavior was independently linked to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.4,5,9,19

Distributions of the incidences of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts varied by gender; therefore, data obtained from males and females were analyzed separately in all analyses. Chi-square tests were used to examine the differences between males and females in the lifetime prevalence of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse (Table 1). Distribution of all variables was also presented by gender (Table 2). Descriptive analyses were performed using a chi-square test and univariate logistic regression analysis to investigate the associations between early initiation of problem behaviors and suicidal behaviors (Table 3). To avoid any possible confounding effects among our primary variables, multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted and included all covariates (Table 4). Multivariate analyses were also performed to determine the effect of concurrent participation in these problem behaviors on each outcome (Table 5). The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.1).

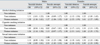

Table 1 shows the grade at first participation in alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse by gender. Overall, the lifetime prevalence for alcohol drinking (61.9% of males vs. 61.1% of females, p = 0.034), cigarette smoking (32.0% vs. 22.1%, p < 0.001), and sexual intercourse (6.4% vs. 3.2%, p < 0.001) was higher in males than in females. In addition, more males than females reported consuming alcohol (19.9% of males vs. 15.2% of females, p < 0.001), smoking tobacco (13.2% vs. 7.9%, p < 0.001), and having sexual intercourse (1.1% vs. 0.4%, p < 0.001) before attending middle school (preteen initiators).

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive information for all variables by gender. In general, females showed a greater risk for suicidal ideation (26.8% of females vs. 18.1% of males, p < 0.001), suicide attempts (5.5% vs. 4.1%, p < 0.001), unhealthy weight control behavior (57.5% vs. 31.0%, p < 0.001), sleep dissatisfaction (43.6 % vs. 37.7%, p < 0.001), and depression (45.8% vs. 35.7%, p < 0.001) than did males. However, current alcohol drinking (26.9% of females vs. 30.0% of males, p < 0.001), cigarette smoking (7.9 of females vs. 14.0% of males, p < 0.001), and butane gas or glue sniffing (0.9% of females vs. 1.8% of males, p < 0.001) were more prevalent in boys than in girls.

Table 3 provides the gender specific percentage distributions and unadjusted odds ratios (95% confidential intervals) of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts by all key variables, including the three problem behaviors. Male and female adolescents who had already initiated these behaviors at any period (either teen or preteen initiators) were at greater risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts compared to non-initiators of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, or sexual intercourse. In particular, younger initiation of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, or sexual intercourse was correlated with greater likelihood of suicidal ideation and actual attempts. That is, male and female preteen initiators were at much greater risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than were male and female teen initiators.

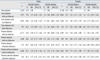

Table 4 presents the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis in the form of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the associations among alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse initiation with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, after controlling for all covariates. As observed in the descriptive analysis, although the magnitudes of the associations of problem behaviors with suicidal behaviors were considerably attenuated when covariates were taken into account, their associations remained significant, except with regard to some male and female teen or preteen initiators. This finding indicated that preteen initiation of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse was independently and significantly associated with elevated likelihood of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in both genders. Moreover, such associations were stronger among the preteen initiator group than among the teen initiator and non-initiator groups.

Table 5 displays the results of the multivariate analysis focusing on concurrent involvement in problem behaviors, and presenting logistic regression parameter estimates as odds ratios. Overall, the odds ratios increased as the frequency of concurrent engagement in problem behaviors increased during the same period of initiation. Interestingly, the odds ratios showed different patterns of associations between problem behaviors and suicidal behaviors according to when the former was initially experienced. Preteen initiators were at greater risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than were teen initiators given concurrent participation at identical frequencies in problem behavior(s). Indeed, preteen and teen initiators with two or more problem behaviors appeared much more likely to demonstrate suicidal behaviors than teen initiators reporting the same frequency of problem behaviors, but less likely than preteen initiators alone.

Using a large nationally representative sample of Korean adolescents, we found that early initiation of each problem behavior (i.e., alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse) was independently and significantly associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, even when all covariates were controlled (e.g., sociodemographic characteristics, substance use, unhealthy behaviors, and psychological disorders). A similar pattern of correlations was revealed in both genders. This finding underscores that adolescent males and females whose initiation into alcohol use, tobacco use, or sexual intercourse occurred in childhood may be vulnerable to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescence. Understanding why those who have engaged in drinking, smoking, or sexual intercourse during their early lives go on to seriously consider and/or attempt suicide in later life is a complex task. It is possible that individuals with early exposure to these problem behaviors tend to be at higher risk not only for later alcohol abuse/dependence, nicotine dependence, unwanted pregnancy, abortion, and sexually transmitted diseases but also for later illicit drug abuse and antisocial characteristics, potentially leading them to consider and/or to attempt suicide.10,11,14,17,20 This finding is consistent with previous studies among U.S. high school students12,13 reporting that preteen alcohol use (i.e., before age 13), compared to abstinence during this period, was significantly associated with both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, and that initiation of alcohol use during the teen years showed a similar but less significant association with suicide and suicidal behavior. Cho et al.9 also found a significant association between cigarette smoking and suicidal ideation among adolescent males and females in the U.S., but did not find a relationship between early alcohol drinking and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in either gender. Differences between these data and our results may be attributable to differences between the studies in terms of the measures employed; in particular, early onset of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking in the former study (e.g., the grade in which a young person first got drunk and started smoking regularly) tended to be more conservative than those in our study (e.g., the grade in which they first drank alcohol and smoked). Both problem behaviors were treated as categorical variables in this study, whereas as continuous variables in the previous study. We do not know whether the measurement of the sexual intercourse variable used in this study was construed as including forced sexual intercourse; however, if so, our results support those of previous studies showing that both male and female adolescents who have been forced to have sexual intercourse appeared more likely to engage in serious suicidal ideation.7,8 Since we measured onset variables less conservatively than did previous studies, our findings may have derived stronger implications than previous studies regarding the early initiation of alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and/or sexual intercourse on suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Another distinctive finding of this study emerged in regard to the association between the likelihood of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts and the time at which the problem behaviors were initially enacted and whether they were enacted concurrently. That is, the likelihood of both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts increased when these problem behaviors were enacted concurrently, particularly among preteens. This finding also provided further evidence for our first hypothesis, and indicated that concurrent participation in multiple problem behaviors had a synergistic effect on suicidal behaviors, and that this synergistic effect may be more detrimental to preteen initiators. Further investigation is necessary to identify the patterns underlying these issues.

This study had several limitations that should be considered in interpreting and generalizing these findings. First, our findings were based on self-reported data in the absence of corroboration from other sources. In addition, each variable (e.g., depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts) was measured by a single item rather than by a scale consisting of multiple items; this may have resulted in reliability and validity problems. Nonetheless, most recent previous studies focusing on various racial and ethnic groups have used this self-reported single question method, and this trend has increased in recent years.4-7,12,13 Second, the main predictor variables (problem behaviors) used herein were addressed retrospectively. Moreover, these variables generally carry socio-cultural taboos for adolescent populations. Thus, it is possible that study participants did not answer accurately. In addition, our data were obtained from only middle and high school students, thereby excluding those who had dropped out of school and/or had a poor attendance record at the time of the survey, and we also omitted those who did not answer three primary questions (i.e., the onset of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking and sexual intercourse) from the analysis, even though this excluded group might be characterized by disproportionately greater participation in problem and suicide-related behaviors.12 Thus, because of these biases, our conclusions may be understated. Third, because certain variables were not addressed in the KYRBWS data, this study could not consider several forms of psychopathology that have been directly or indirectly associated with suicidal behaviors, including adverse childhood experiences, aggressiveness, eating disorders, clinical symptoms, and social support and capital.2-4 Finally, the KYRBWS included information on onsets of the problem behaviors but did not include information on onsets of the outcomes. Consequently, we were unable to draw inferences about the causal pathways between problem behaviors and suicide-related behaviors among Korean adolescents. Therefore, future research should consider adopting a longitudinal design to examine the relationships among our focal issues with greater precision.

Despite these limitations, this study has several important strengths. The major strength of the present study was its use of a nationally representative sample and its high response rate, which may enable to generalize our findings to the actual population of Korean adolescents. Moreover, this study was the first to analyze measures of simultaneous alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse, yielding indications that early initiations of problem behaviors are important predictors of later suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Korean adolescent males and females. In particular, preteens were more susceptible than teens to the synergistic effects of combinations of these problem behaviors. Given recent trends and unlimited access to alcohol, tobacco, and internet and/or cyberspace sex in modern Korean society, it is not surprising that the age at which problem behaviors manifest continues to decrease. Consequently, the rates of adolescent suicide-related behaviors may continue to increase in the future. In particular, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescence have been identified as important predictors of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adulthood.21 Therefore, integrated preventive intervention programs targeting the concurrent initiation of alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and sexual intercourse, especially among preteens, should take precedence over those focused on each of these issues separately, thereby reducing the potential risks for subsequent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Grade at First Participation in Alcohol Drinking, Cigarette Smoking, and Sexual Intercourse in Korean Adolescent Males (n = 32,417) and Females (n = 31,467)

Table 3

Percentage Distributions and Unadjusted Odds Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) of the Study Variables by Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts in Korean Adolescent Males and Females

Table 4

Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals)* for the Associations of Early Initiation of Alcohol Drinking, Cigarette Smoking and Sexual Intercourse with Sucidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts in Korean Adolescent Males and Females

References

1. 2005 Annual report on the causes of death statistics, Korea National Statistical Office. Korea National Statistical Office. accessed August 6, 2008. Available from:

http://www.kosis.kr.

2. Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006. 47:372–394.

3. Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K. Factors associated with suicidal phenomena in adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004. 24:957–979.

4. Kim DS. [Experience of parent-related negative life events, mental health, and delinquent behavior among Korean adolescents]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2007. 40:218–226.

5. Kim DS. Body image dissatisfaction as an important contributor to suicidal ideation in Korean adolescents: gender difference and mediation of parent and peer relationships. J Psychosom Res. 2009. 66:297–303.

6. Torikka A, Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M, Rimpelä A, Rantanen P, Rimpela M. Drinking, other substance use and suicidal ideation in middle adolescence: a population study. J Subst Use. 2002. 7:237–243.

7. Basile KC, Black MC, Simon TR, Arias I, Brener ND, Saltzman LE. The association between self-reported lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse and recent health-risk behaviors: findings from the 2003 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006. 39:752.e1–752.e7.

8. Chen J, Dunne MP, Han P. Child sexual abuse in Henan province, China: association with sadness, suicidality, and risk behaviors among adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2006. 38:544–549.

9. Cho H, Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ. Early initiation of substance use and subsequent risk factors related to suicide among urban high school students. Addict Behav. 2007. 32:1628–1639.

10. DuRant RH, Smith JA, Kreiter SR, Krowchuk DP. The relationship between early age of onset of initial substance use and engaging in multiple health risk behaviors among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999. 153:286–291.

11. Gruber E, Diclemente RJ, Anderson MM, Lodico M. Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Prev Med. 1996. 25:293–300.

12. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. Gender, early alcohol use, and suicide ideation and attempts: findings from the 2005 youth risk behavior survey. J Adolesc Health. 2007. 41:175–181.

13. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Sullivent EE 3rd. Age of alcohol use initiation, suicidal behavior, and peer and dating violence victimization and perpetration among high-risk, seventh-grade adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008. 121:297–305.

14. Howard DE, Wang MQ. Psychosocial correlates of U.S. adolescents who report a history of forced sexual intercourse. J Adolesc Health. 2005. 36:372–379.

15. Jessor R. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. 1998. 1st ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press;135.

16. Kim YM. A study on concurrent use of alcohol and cigarette among adolescents. Ment Health Soc Work. 2005. 20:40–68.

17. Schmid B, Hohm E, Blomeyer D, Zimmermann US, Schmidt MH, Esser G, et al. Concurrent alcohol and tobacco use during early adolescence characterizes a group at risk. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007. 42:219–225.

18. Kim YT, Lee YK, Kim YJ, Yoon PK, Park JY, Jung SH, et al. The second annual report on the statistics of youth risk behavior web-based survey. Accessed August 28, 2008. Available from:

http://healthy1318.cdc.go.kr.

19. Kim DS. Gender differences in body image and suicidal ideation among Korean adolescents [dissertation]. 2008. Seoul: Seoul National University;48–51.

20. McGue M, Iacono WG. The association of early adolescent problem behavior with adult psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry. 2005. 162:1118–1124.

21. Herba CM, Ferdinand RF, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Long-term associations of childhood suicide ideation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007. 46:1473–1481.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download