Abstract

Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma (ETTL) is a rare disease with a poor prognosis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, it is a subtype of the peripheral T-cell lymphomas. This disease is associated with gluten-sensitive enteropathy, has a high risk of intestinal perforation and obstruction, and is refractory to chemotherapeutic treatment. We report the case of a 73-year-old woman who was diagnosed with enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma of the small intestine, which was positive for the markers of cytotoxic T cells, CD3, CD8, and CD56, on immunohistochemical staining after resection of the perforated terminal ileum.

Gastrointestinal lymphomas accounts for 4-20% of all non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma (ETTL) accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin's lymphomas.1,2 There are two types of ETTL according to the Association of Celiac Disease. Secondary ETTLs can develop in 7-10% of patients with gluten-sensitive enteropathy (GSE, celiac disease).1,3 However, in case of refractory celiac disease with a phenotypically aberrant intraepithelial T-cell population, the transition into ETTL is more common (52%).3 There are also de novo ETTLs without a preceding history of complicated celiac disease. These lymphomas also entail a high risk of intestinal perforation or obstruction, and are refractory to chemotherapy. ETTL generally has a poor prognosis because of its delayed diagnosis and frequent dissemination.4 Al-toma, et al.3 reported a 2-year survival in the de novo ETTL and secondary ETTL were 20% and 15%, respectively. We recently encountered a case in which an ETTL caused small bowel perforation but lacked any association with GSE.

A 73-year-old woman attended our hospital emergency department after a sudden onset of severe abdominal pain and fever. A physical examination revealed a high fever (39℃), a chilling sensation, abdominal tenderness, and muscular defense. The patient had none of the following symptoms: diarrhea, body-weight loss, history of malnutrition, or food intolerance. We could not detect any palpable cervical lymph node.

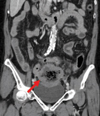

The laboratory tests on admission showed mild leukocytosis (white blood cell count of 13,050/mm2) and azotemia (serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine of 18/1.2 mg/dL). Peripheral blood morphology indicated normocytic normochromic anemia (hemoglobin of 9.9 g/dL) with anisopoikilocytosis, and the patterns of serum electrophoresis were nonspecific. A chest radiography revealed no definite free air under the diaphragm. Abdominal computed tomographic imaging showed an 8.5 cm length of wall thickening in the distal small bowel, with central necrosis and pseudoaneurysmal dilatation. Within the pelvic area, multiple homogeneous enhancing lymphadenopathies were present on the mesentery near the mass (Fig. 1). In light of these factors, we planned a laparoscopic exploration for a suspected malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

The laparoscopic findings showed localized peritonitis arising from the perforation of the terminal ileum and that the lesion was adherent to the bladder and the sigmoid colon. We performed a segmental resection of the perforated ileum and side-to-side anastomosis through a minilaparotomy after a meticulous dissection. The central wall of the resected ileum was diffusely thickened and it showed a relatively well-defined encircling the mural mass measuring 10.0 cm in length. The mass was gray-white to tan and indicated hemorrhage and necrosis (Fig. 2).

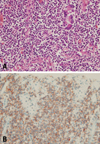

In the pathology report, immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD5, CD3, CD56, CD8, and Ki-67, and negative for CD20, CD15, and the Epstein-Barr virus (Fig. 3). The T-cell nature of the tumor was reflected in its reactivity for CD3 and CD8, and its negativity for the B-cell marker CD20. The patient expressed the HLA-DQ6 and HLA-DQ9 alleles. On the basis of the immunohistochemical and microscopic findings, we made a diagnosis of ETTL.

ETTL accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. It is a subtype of the peripheral T-cell lymphomas in the World Health Organization classification and it is known to develop in 7-10% of patients with long-standing GSE.1 A patient with ETTL and GSE generally presents with diarrhea, food intolerance, and laboratory findings suggestive of nutrient malabsorption. Immunoglobulin A antigliadin and antiendomysial antibodies are also present in the serum. About 90% of patients with GSE carry the HLA-DQ2 allele.5 The diagnosis of ETTL requires an adequate biopsy and immunophenotyping. Macroscopically, ETTL is often multifocal, with ulcerative lesions mainly on the jejunum, and there is a high risk of intestinal perforation and obstruction.4

Immunophenotyping in most cases demonstrates CD3+, CD4-, CD8-, and CD1O3+, or occasionally CD3+, CD4-, CD8+, CD56+, and CD103+, and the cells express markers of activated cytotoxic T cells.2 Several studies have suggested that the Epstein-Barr virus plays an etiological role in the pathogenesis of ETTL, but this view is still quite debatable.6

The treatment of ETTL involves chemotherapy with clophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP).3 If the ETTL is associated with GSE, gluten should be withdrawn from the diet.1,2 However, the disease is usually highly refractory to chemotherapy and is exacerbated by recurrent bowel perforation, obstruction, or other complications. ETTL is a high-grade intestinal T-cell lymphoma with a poor prognosis. Novakovic reported that the one-year and five-year survival rates of patients with intestinal T-cell non-Hodgkin's disease are 33% and 9%, respectively.2,7

In summary, we report the case of a 73-year-old woman who was diagnosed with ETTL of the small intestine after segmental resection of a perforated terminal ileum.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Hönemann D, Prince HM, Hicks RJ, Seymour JF. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma without a prior diagnosis of coeliac disease: diagnostic dilemmas and management options. Ann Hematol. 2005. 84:118–121.

2. Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Rambaud JC. Gastrointestinal lymphoma: prevention and treatment of early lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001. 15:337–354.

3. Al-Toma A, Verbeek WH, Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Mulder CJ. Survival in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: retrospective evaluation of single-centre experience. Gut. 2007. 56:1373–1378.

4. Brousse N, Meijer JW. Malignant complications of coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005. 19:401–412.

5. Ciclitira PJ, Moodie SJ. Transition of care between paediatric and adult gastroenterology. Coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003. 17:181–195.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download