Abstract

Coronary-subclavian steal through the left internal mammary graft is a rare cause of myocardial ischemia in patients who have had a coronary bypass surgery. We report a 70-year-old man who presented with sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia 5 years after the surgical creation of a left internal mammary to the left anterior descending artery. Cardiac catheterization illustrated that the left subclavian artery was occluded proximally and that the distal course was visualized by retrograde filling through the left internal mammary graft. Clinical ventricular tachycardia was reproducibly induced with a single ventricular extrastimulus, and antitachycardia pacing terminated the tachycardia. Restoration of blood flow by way of a Dacron graft placed between the descending aorta and the subclavian artery resulted in the total relief of symptoms. Ventricular tachycardia could not be induced during the control electrophysiologic study after surgical revascularization.

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome, which is defined as a collateral blood flow from a coronary artery to the subclavian artery through the left internal mammary artery (LIMA), is a rare but significant cause of ischemia after the coronary artery bypass surgery.1 In this syndrome, because of the total occlusion of the subclavian artery, the flow of blood in the LIMA is reversed and directed to the subclavian artery instead of the coronary artery. Very few case reports have described this syndrome, and the main symptom in these cases has been angina or pain related to the upper extremity.

We report a patient with coronary-subclavian steal syndrome who was diagnosed with sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia five years after the coronary artery bypass surgery. This patient underwent re-operation for a bypass graft between the descending aorta and the left subclavian artery, which caused a full relief of ventricular tachycardiac episodes.

A 70-year-old man showed signs of palpitation on mild exertion. He described chest pain and palpitations while walking for the past year. On admission, the heart rate was 200 beats per minute, and the arterial blood pressure was 60/30 mmHg in his right arm and was not measurable in the left arm. Surface ECG showed a sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia with a left bundle branch block pattern and an inferior QRS axis (Fig. 1). After tachycardia, which causes hemodynamic compromise, was terminated with a 200-joule DC shock, sinus rhythm was restored. The patient's history revealed that this man had had an anterior myocardial infarction and had undergone coronary artery bypass surgery using LIMA to the left anterior descending artery (LAD) 5 years ago. Recently, the patient began to feel chest pain episodes especially while using his arms. When he stopped working, these pain symptoms were spontaneously resolved within minutes. The patient was on digoxin, β-blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, and nitrate therapy. Upon physical examination, the patient's pulse rate was regular at 80 bpm, and the arterial blood pressure was 140/70 mmHg and 80/30 mmHg in the right and left arms, respectively. On auscultation, there was a 2/6 grade systolic murmur at the apex. An electrocardiography showed QS waves in the precordial leads, suggesting an old anterior myocardial infarction. The cardiac shadow was enlarged on a chest X-ray. An echocardiogram demonstrated septal and anterior wall akinesia and decreased the left ventricular function with an ejection fraction of 30%.

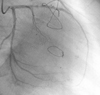

Initially, the left subclavian artery could not be located. An aortography, which was performed through the right femoral artery using the Judkins' technique, showed total occlusion from just 2 cm below the ostium of the left subclavian artery (Fig. 2). There was no retrograde flow from the vertebral artery to the subclavian artery. Left coronary angiography showed 80% stenosis of the LAD (Fig. 3). Also, the contrast material was flowing retrogradely into the LIMA graft and further into the left subclavian artery (Fig. 4). The circumflex and right coronary arteries were normal.

In the electrophysiologic (EP) study, AH and HV intervals were 110 msec and 52 msec, respectively, during the background sinus rhythm. Clinical ventricular tachycardia (VT) with a left bundle branch block pattern and an inferior QRS axis morphology with a cycle length of 300 msec was reproducibly induced by triple extrastimuli delivered to the right ventricle (Fig. 5). Thus, the origin of the VT was thought to be the anterior basal septum, which is the territory of LAD, as would be expected. The tachycardia was terminated with antitachycardia pacing.

With these findings, a decision was made to proceed with surgical treatment. A Dacron type bypass graft was placed between the descending aorta and the subclavian artery just below the LIMA, end-to-side and end-to-end, respectively. On the seventh postoperative day, the patient was taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory again. Aortography revealed that the subclavian artery was filled through the graft and the direction of flow in the LIMA was from the subclavian artery to the LAD. In the control EP study, no tachycardia was induced by a programmed stimulation, including the triple extrastimuli with three different cycle lengths of pacing at two different regions in the right ventricle, before and after isoproterenol infusion. The patient refused to have an implantable cardioverter defibrilator (ICD) and was discharged without complications 10 days after the operation on amiodarone and antiischemic medications as prescribed before. After about 6 months, the patient accepted an ICD implantation, and antiarrhythmic therapy was continued. The patient has been free of symptoms during a follow-up period of 15 months.

LIMA is the conduit of choice for cardiac revascularization. The phenomenon of retrograde flow in this graft that is secondary to the proximal occlusion of the subclavian artery is a rare entity that has been termed the "coronary-subclavian steal syndrome". Angina pectoris and symptoms that are related to the upper extremities have been associated with this phenomenon.2-7 In this study, the patient was diagnosed with ventricular tachycardia (VT), which has not previously been reported ever". Since the VT could not be induced after the aorta-subclavian bypass operation, we hypothesized that VT was caused by the coronary-subclavian steal syndrome and resultant ischemia.

In the reported cases, the most significant finding was the difference between the arterial blood pressures in both arms. This diagnosis is considered in patients in whom ischemia is still demonstrable after the coronary artery bypass surgery utilizing LIMA and when the blood pressure difference between both upper extremities is more than 20 mmHg.2-7

The therapy of choice for the coronary-subclavian steal syndrome is surgical revascularization. The only case of rejection of this operation was reported by Bryan et al.2; however, the patient of this case died after 12 months. We can speculate that, without surgery, our patient would be at high risk for a sudden cardiac death due to fatal arrhythmias. Angioplasty to the subclavian artery has been reported as an alternative to surgery.8-10 The graft can be placed from the carotid artery or aorta to the subclavian artery, or alternatively, the proximal part of the LIMA can be transferred to some other arterial source, in particular, the aorta.1-3,6,7 Because there was heavy calcification at the occlusion site of the subclavian artery, our choice of therapy was surgical revascularization of the left upper extremity, and the carotid artery was not preferred for anastomosis because of its thin calibration.

EP study can be used to study the mechanisms and hemodynamic consequences of the VT for risk assessment of patients with clinically documented tachycardias and also can be used to establish the response to antitachycardia pacing as well as the efficacy of medical therapy.

It was shown that ventricular arrhythmia can be induced with exercise-related ischemia and can be suppressed after the correction of ischemia in patients with a history of myocardial infarction.11 Geelen, et al.,12 showed that the number of shocks delivered by the ICD decreased after revascularization. These findings support the role of acute ischemia in triggering malign ventricular arrhythmias in patients with a chronic substrate. In our case, the tachycardia was no longer inducible at the control EP study done after surgical revascularization. However, the patient was treated with ICD because noninducibility does not exclude the possibility of VT in daily life settings of the depressed left ventricular function and in the history of myocardial infarction.13

In summary, we report an unusual case of coronary-subclavian steal syndrome presented with ventricular tachycardia. In such patients, an ischemic trigger should be sought and corrected, if found.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Surface electrogram shows sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia with a left bundle branch block pattern and an inferior QRS axis. |

| Fig. 2Aortography shows the total occlusion from just 2 cm below of the ostium of the left subclavian artery. |

| Fig. 3Left coronary angiography reveals severe stenosis of the proximal LAD and normal circumflex artery. Additionally, blood flow is observed into the LIMA from the LAD (right anterior oblique projection). LAD, left anterior descending; LIMA, left internal mammary artery. |

References

1. Horowitz MD, Oh CJ, Jacobs JP, Chahine RA, Livingstone AS. Coronary-subclavian steal: a cause of recurrent myocardial ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg. 1993. 7:452–456.

2. Bryan FC, Allen RC, Lumsden AB. Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome: report of five cases. Ann Vasc Surg. 1995. 9:115–122.

3. Norsa A, Gamba G, Ivic N, Peranzoni P, Brunelli M, Pasquin I, et al. The coronary subclavian steal syndrome: an uncommon sequel to internal mammary-coronary artery bypass surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994. 42:351–354.

4. Tuseth V, Hegland O, Fietland L, Nilsen DW. Reversed flow in internal mammary artery conduit and vertebral artery with left subclavian artery occlusion causing angina and vertigo. The coronary--subclavian steal syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2001. 79:311–314.

5. Mary-Rabine L, Henroteaux D, Pourbaix S. [Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome: an unusual cause of recurrent myocardial ischemia following aortocoronary bypass.]. Rev Med Liege. 1994. 49:342–345.

6. Rashkow AM. Angina pectoris caused by subclavian coronary steal. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1993. 30:230–232.

7. Philippe F, Folliguet T, Carbogniani D, Dibie A, Bouabdallah K, Larrazet F, et al. [Coronary subclavian steal syndrome after internal mammary artery bypass grafting. A cause of severe postoperative recurrent myocardial ischemia.]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2000. 93:1555–1559.

8. Nguyen NH, Reeves F, Therasse E, Latour Y, Genest J Jr. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in coronary-internal thoracicsubclavian steal syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 1997. 13:285–289.

9. Kneale BJ, Irvine AT, Coltart DJ. Coronary subclavian steal syndrome following coronary by-pass surgery. Postgrad Med J. 1996. 72:358–360.

10. Wallis F, Kidney D, Molloy M. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of subclavian stenosis to improve inflow to internal mammary coronary arterial grafts. Eur Radiol. 1996. 6:220–223.

11. Codini MA, Sommerfeldt L, Eybel CE, De Laria GA, Messer JV. Efficacy of coronary bypass grafting in exercise-induced ventricular tachycardia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1981. 81:502–506.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download