Abstract

Purpose

We identified pediatric liver transplant recipients with successful withdrawal of immunosuppression who developed tolerance in Korea.

Materials and Methods

Among 105 pediatric patients who received liver transplantation and were treated with tacrolimus-based immunosuppressive regimens, we selected five (4.8%) patients who had very low tacrolimus trough levels. Four of them were noncompliant with their medication and one was weaned off of immunosuppression due to life threatening posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. We reviewed the medical records with regard to the relationship of the donor-recipients, patient characteristics and prognosis, including liver histology, and compared our data with previous reports.

Results

Four patients received the liver transplantation from a parent donor and one patient from a cadaver donor. A trial of withdrawal of the immunosuppressant was started a median of 45 months after transplantation (range, 14 months to 60 months), and the period of follow up after weaning from the immunosuppressant was a median of 32 months (range, 14 months to 82 months). None of the five patients had rejection episodes after withdrawal of the immunosuppression; they maintained normal graft function for longer than 3 years (median, 38 months; range, 4 to 53 months). The histological findings of two grafts 64 and 32 months after weaning-off of the medication showed no evidence of chronic rejection.

As survival has improved after liver transplantation, with potent immunosuppressants like tacrolimus, the quality of life and long-term immunosuppression have become important factors in addition to acute rejection and graft survival. There are reports on liver transplant recipients who acquire tolerance.1 We identified pediatric liver transplant recipients with successful withdrawal of immunosuppression who developed tolerance and analyzed the patient characteristics, donor-recipient relationship, immunosuppressant regimens, and prognosis.

From April 1997 to July 2007, 105 pediatric liver transplantation recipients received tacrolimus-based immunosuppression at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. Among them, we selected five patients (4.8%) who had a very low tacrolimus trough level (< 1 ng/mL by Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/MS). Four of them had frequently refused to take the immunosuppressive drug; they were interviewed to confirm the noncompliance. Finally, four patients weaned due to noncompliance and one patient weaned due to life threatening posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) were enrolled. The median age at transplantation was three years (range, 8 months to 9 years). The primary diseases were biliary atresia (n = 2), neonatal hepatitis of unknown cause (n = 1) and hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 2). Four patients received living-related liver transplantation from their parent and one patient received a cadaver transplant. All five patients underwent immunosuppression induced with a steroid and tacrolimus regimen during the early stage of liver transplantation and were maintained on tacrolimus-based immunosuppression. Monitoring of graft function was followed by blood tests to assess liver function. In cases of abnormal findings in the blood tests, suspicion of rejection, a liver biopsy was performed.

We reviewed the medical records and analyzed the clinical characteristics of the patients who discontinued immunosuppression, and retrospectively evaluated the immunologic relationship with their donor (blood type), immunologic status of a specific virus at pre-transplantation [Ebstein-Barr Virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV)], time between transplantation and immunosuppressant withdrawal, follow-up period after immunosuppressant withdrawal, episodes of rejection, and graft function. In addition, we attempted to confirm their histological graft status by performing a liver biopsy in two of the patients 64 and 32 months after withdrawal of immunosuppression.

Four patients received the liver transplantation from a parent donor and one patient from a cadaver donor. The immunosuppression regimen was steroid and tacrolimus treatment for a median of six months (range, 2 months to 9 months) after transplantation, followed by maintenance with tacrolimus for a median of 38 months (range, 4 months to 53 months) (Fig. 1). During the maintenance period, all patients had stable liver function. Three patients were treated with pulse steroid therapy and dose up tacrolimus therapy when there was suspicion of acute rejection; two patients were confirmed to have acute rejection by liver biopsy within a month after transplantation. None of the five patients had rejection episodes for over 1 year (range, 14 months to 82 months) after withdrawal of the immunosuppression.

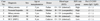

Among the five cases, there were ABO blood type-identical grafts in three cases and compatible grafts in two. Three patients were EBV high-risk (EBV seronegative recipients from EBV seropositive donor); one of them developed life threatening gastrointestinal PTLD and was weaned off immunosuppression 14 months post-transplantation. All five patients were CMV IgG positive pre-transplantation; there were no complications associated with CMV infection throughout the follow-up after transplantation (Table 1).

A trial of withdrawal of immunosuppressant was started a median of 45 months after transplantation (range, 14 months to 60 months), and the period of follow up after weaning from the immunosuppressant was a median of 32 months (range, 14 months to 82 months). None of the five patients had rejection episodes after withdrawal of immunosuppression; four of them maintained normal graft function for longer than 3 years (median, 38 months; range, 4 to 53 months) (Table 2). There was no case of an immune-mediated primary liver disease. Two of the four noncompliant patients (patient 1 and 3) were intentionally weaned from their medication. The main reason for weaning off the immunosuppression was parents' anxiety about the complications from immunosuppression therapy. The other two noncompliant patients (patient 4 and 5) had taken the medication irregularly. These two older children refused to take the life-long medication.

We compared these five patients with previous reports to determine the favorable clinical markers and selection criteria for discontinuation of immunosuppression (Table 3). Devlin, et al.2 and Takatsuki, et al.3 reported on the withdrawal of immunosuppression, including pediatric liver transplant recipients, and analyzed the favorable markers for successful withdrawal of immunosuppression and the selection criteria for elective weaning. The five patients reported here had non-immune mediated liver disease, long-term maintenance of normal graft function without rejection and were all pediatric recipients. Excluding the one patient with PTLD, four patients attempted to wean the immunosuppressant treatment two years post-transplantation.

We performed a liver biopsy in two of our patients at 64 months and 32 months after withdrawal of the immunosuppressant to rule out chronic rejection in spite of their normal liver function. The histological findings of their grafts showed normal hepatic architecture without any evidence of acute cellular or chronic rejection (Fig. 2).

Tolerance is defined as the clinical situation when a graft maintains stable function without the need for chronic immunosuppression;4 it occurs more frequently in liver allografts than with other solid organ transplantation. Some reports support elective immunosuppressive drug weaning for selected liver transplant recipients.1 It is thought that donor cell chimerism is associated with donor specific tolerance and allograft acceptance. Studies reporting on the possibility of these hypotheses have not revealed the exact mechanism underlying tolerance.5-7 Thomson, et al.4 attempted to evaluate the validity of immunologic and biologic tests that correlated with and were predictive of a state of tolerance. They analyzed dendritic cell types, cytokine secretion, donor specific antibody prevalence, and cytokine genotypes, however, failed to identify any clinically useful markers. Mazariego, et al.8 suggested that an increased ratio of plasmacytoid dendritic cell to myeloid dendritic cell was a significant factor for achieving operational tolerance. Therefore, the mechanism underlying tolerance is not known, and there have been no large-scale studies of elective weaning off of immunosuppressant treatment. There are only a limited number of studies on accidentally weaned noncompliant patients and withdrawal of immunosuppressant due to severe infection or PTLD, or small groups of selectively chosen patients for elective weaning at certain centers.1-3,9-14

Mazariego, et al.12 reported that azathioprine/prednisone- and tacrolimus-based treatment of patients were more likely to be off drugs at one year after transplantation compared to cyclosporine treated patients, and Takatsuki, et al.3 suggested that the graft survival was better in patients who received a living-related donor transplantation. Lerut, et al.1 reviewed reports on the withdrawal of immunosuppression and found that immunosuppression withdrawal is possible in 19.4% of transplant recipients, and that the common favorable clinical markers were: 1) an age > two years post liver transplantation, 2) a low incidence of rejection, 3) non-immune mediated liver disease, and 4) minimal immunosuppression. Most of the prospective elective withdrawal studies included patients followed for longer than two years. However, Eason, et al.10 enrolled patients with less than six months of follow-up, and only one of their eighteen patients was weaned off the immunosuppression successfully. Therefore, it remains unclear when immunosuppression can safely be withdrawn.

Some reports have raised concerns about chronic rejection after withdrawal of immunosuppression.1,15 Koshiba, et al.16 reported that liver biopsy after complete withdrawal of the immunosuppressant revealed changes of the bile duct and fibrosis. However, there were no such findings in our study.

The five patients included in this study had long-term (> 3 years) stable graft function, no rejection for more than 1 year after withdrawal of immunosuppression, non-immune mediated liver diseases, and were all pediatric cases; all of these factors are favorable markers, according to previous reports. Although a small number of patients were studied, this is the first report on tolerance in pediatric liver transplant recipients in Korea after withdrawal of immunosuppression. To improve the quality of life for liver transplant recipients, confirmation of our findings with a multicenter trial is now needed to determine patient factors, clinical timing and biological markers associated with successful immunosuppressant withdrawal.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Liver histologic finding in one patient at 32 months after withdrawal of the immunosuppressant. Hepatic lobular architecture is well preserved showing focal balooning degeneration. Portal space displays intact bile ducts with no inflammatory infiltrate. Mild periportal fibrosis is found (original magnification × 200, Masson Trichrome). |

Table 1

Characteristics of the Subjects

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; R, recipient; D, donor, EBV, Ebstein-Barr Virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

EBV high-risk group: EBV-seronegative patients receiving allograft from EBV-seropositive donors.

EBV low-risk group: EBV- seropositive recipient or EBV-seronegative patients receiving allograft from EBV-seronegative donors.

References

1. Lerut J, Sanchez-Fueyo A. An appraisal of tolerance in liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006. 6:1774–1780.

2. Devlin J, Doherty D, Thomson L, Wong T, Donaldson P, Portmann B, et al. Defining the outcome of immunosuppression withdrawal after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1998. 27:926–933.

3. Takatsuki M, Uemoto S, Inomata Y, Egawa H, Kiuchi T, Fujita S, et al. Weaning of immunosuppression in living donor liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2001. 72:449–454.

4. Thomson AW, Mazariegos GV, Reyes J, Donnenberg VS, Donnenberg AD, Bentlejewski C, et al. Monitoring the patient off immunosuppression. Conceptual framework for a proposed tolerance assay study in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2001. 72:8 Suppl. S13–S22.

5. Starzl TE, Demetris AJ, Murase N, Ildstad S, Ricordi C, Trucco M. Cell migration, chimerism, and graft acceptance. Lancet. 1992. 339:1579–1582.

6. Pons JA, Yélamos J, Ramírez P, Oliver-Bonet M, Sánchez A, Rodríquez-Gago M, et al. Endothelial cell chimerism does not influence allograft tolerance in liver transplant patients after withdrawal of immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2003. 75:1045–1047.

7. Tryphonopoulos P, Tzakis AG, Weppler D, Garcia-Morales R, Kato T, Madariaga JR, et al. The role of donor bone marrow infusions in withdrawal of immunosuppression in adult liver allotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005. 5:608–613.

8. Mazariegos GV, Zahorchak AF, Reyes J, Ostrowski L, Flynn B, Zeevi A, et al. Dendritic cell subset ratio in peripheral blood correlates with successful withdrawal of immunosuppression in liver transplant patients. Am J Transplant. 2003. 3:689–696.

9. Hurwitz M, Desai DM, Cox KL, Berquist WE, Esquivel CO, Millan MT. Complete immunosuppressive withdrawal as a uniform approach to post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2004. 8:267–272.

10. Eason JD, Cohen AJ, Nair S, Alcantera T, Loss GE. Tolerance: is it worth the risk? Transplantation. 2005. 79:1157–1159.

11. Massarollo PC, Mies S, Abdala E, Leitão RM, Raia S. Immunosuppression withdrawal for treatment of severe infections in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1998. 30:1472–1474.

12. Mazariegos GV, Reyes J, Marino I, Flynn B, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Risks and benefits of weaning immunosuppression in liver transplant recipients: long-term follow-up. Transplant Proc. 1997. 29:1174–1177.

13. Mazariegos GV, Reyes J, Marino IR, Demetris AJ, Flynn B, Irish W, et al. Weaning of immunosuppression in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1997. 63:243–249.

14. Tisone G, Orlando G, Cardillo A, Palmieri G, Manzia TM, Baiocchi L, et al. Complete weaning off immunosuppression in HCV liver transplant recipients is feasible and favourably impacts on the progression of disease recurrence. J Hepatol. 2006. 44:702–709.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download