Abstract

Although cysticercosis is the most common parasitic disease affecting the central nervous system, spinal cysticercosis is rare. A rare form of spinal cysticercosis involving the whole spinal canal is presented. A 45-year-old Korean male had a history of intracranial cysticercosis and showed progressive paraparesis. Spinal magnetic resonance scan showed multiple cysts compressing the spinal cord from C1 to L1. Three different levels (C1-2, T1-3, and T11-L1) required operation. Histopathological examination confirmed cysticercosis. The patient improved markedly after surgery.

Cysticercosis is a systemic illness caused by Taenia Solium larvae dissemination.1 Although it can occur in almost any tissue, neurocysticercosis (NCC) is the most clinically important manifestation and may present with dramatic findings due to skull and spinal canal confines.2 Though NCC is not rare in Korea,3 spinal neurocysticercosis (SNCC) is (1.5%).3 Its rarity has been explained by the fact that intracranial cysticerci do not pass through the subarachnoid space at the cervical level due to its size.1 Although cases of SNCC have previously been reported, there has been no report of whole spinal canal involvement requiring multiple operations. We present such a rare case.

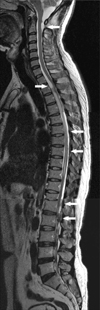

A 45-year-old Korean male presented with a 3-month history of progressive lower limb weakness and voiding difficulty. Fifteen years ago, he had been diagnosed with intracranial cysticercosis. At that time, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed mild hydrocephalus and focal meningitis in the left cerebello-pontine and ambient cistern. A enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of hos cerebrospinal fluid test confirmed cysticercosis,4,5 and the patient completed 2 cycles of oral praziquantel (PZQ; 50 mg/kg per day in 3 divided doses for 14 days)6 and carbamazepine (CMZ; 400 mg per day in 2 divided doses daily) for seizure prophylaxis. He was well until severe headache recurred 10 years later. Brain MRI then revealed slightly aggravated hydroce-phalus. Reactivated NCC was suspected as the patient complained of severe headache, CSF examination showed inflammation, and a CSF ELISA test confirmed cysticercosis. The patient received 3 cycles of albendazole (ABZ; 15 mg/kg per day in 3 divided doses for 7 days), and his antiepileptic was changed to valproic acid (VPA; 900 mg per day in 3 divided doses daily). The patient recovered well until this current presentation. Neurological examination revealed Grade 3 lower limb motor weakness, no sensory abnormality, and alert mental state. Compared with prior MRI results, brain MRI revealed unchanged hydrocephalus and no evidence of cyst or meningitis. However, T2-weighted MR images of the spine demonstrated multiple cysts compressing the spinal cord from C1 to L1 (Fig. 1). The patient underwent surgical removal. Laminectomy from C1 to C2, T1 to T3, and T11 to L1 was performed. Linear incision was made on the dura. Arachnoiditis was noticed focally. Several white encapsulated cysts containing clear fluid adhered to the arachnoid membrane and were dissected with difficulty, but the rest was easily removed. Histopathological examination confirmed cysticercosis. Albendazole (ABZ; 15 mg/kg per day in 3 divided doses for 14 days) was prescribed postoperatively. The patient improved enough to ambulate with a walker and regained urinary function.

Cysticercosis is the most common parasitic disease affecting the central nervous system.1 SNCC is rare compared with intracranial NCC, and its incidence is known to be 0.7 to 5.85%.7 Low incidence of SNCC is explained by the "sieve effect."1 The majority of cysticerci cannot pass through the subarachnoid space at the cervical level due to its size and the physiological sieve.1 CSF reflux at the craniovertebral junction, which propels floating cysts back into the intracranial space rather than the spinal canal, is an another possible reason of why SNCC is rare. On the other hand, there are several possible mechanisms of cysticercosis spinal invasion. 1) Ventricular cysticerci pass through the Magendie or Luschka foramen, and migrate via gravity through the subarachnoid space to inoculate the spinal cord.1,7 The subarachnoid form is explained by this mechanism. The subarachnoid form usually occurs at the cervical level, but our present case demonstrated that it can go as far as the cauda equina. 2) Hematogenous spread has been regarded as the invading mode of the intramedullary form. Spinal blood flow is richest at the thoracic level, which is the most common level for the intramedullary form.8 3) Intraventricular hypertension enables migration through a dilated ependymal canal into the spinal cord. It also explains the invading mode of the intramedullary form.1 Besides, there are several prodromal conditions that make cysticercosis readily invade the spinal contents. These include NCC-related hydrocephalus and/or meningitis, and use of antiepileptics and anithelminithics. SNCC occurs in patients with a prior diagnosis of intracranial NCC in approximately 75% of cases; direct extension of intracranial NCC is implied as the source.1 Antiepileptic drugs, such as carbamazepine and phenytoin, can alter immune function, and therefore, affect susceptibility to parasitic infestation. Although a recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of antihelminthic therapy in patients harboring viable cysts within the brain parenchyma, it is thought to increase inflammation because of cyst involution, leading to worsening clinical states, which might accelerate dissemination of other viable cysticerci.9,10 The long term prognosis of neurocysticercosis is still not satisfactory.3,6,10 Our patient had a long history of intracranial NCC with hydrocephalus and meningitis. In addition, he had long term administration of antihelminthic and antiepileptic drugs. These are thought to be the causative factors of extensive spinal involvement in our patient. Although the subarachnoid form has been frequently reported, there is no previous report to document SNCC involving the whole spinal canal. This case demonstrates a serious manifestation and successful surgical management of SNCC secondary to intracranial NCC.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

T2-weighted MR images of the whole spine, which demonstrate cysts located at the anterior subarachnoid space of T1-2 and posterior arachnoid space of C2, T5-T7, L1, and L2. Increased signal intensity, which indicates edema of the spinal cord, is noted at the level of T2 through T4 and T9 to T10 (arrows).

References

1. Colli BO, Valença MM, Carlotti CG Jr, Machado HR, Assirati JA Jr. Spinal cord cysticercosis: neurosurgical aspects. Neurosurg Focus. 2002. 12:e9.

2. Alsina GA, Johnson JP, McBride DQ, Rhoten PR, Mehringer CM, Stokes JK. Spinal neurocysticercosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2002. 12:e8.

3. Kim SK, Wang KC, Paek SH, Hong KS, Cho BK. Outcomes of medical treatment of neurocysticercosis: a study of 65 cases in Cheju Island, Korea. Surg Neurol. 1999. 52:563–569.

4. Lee JH, Kong Y, Ryu JY, Cho SY. Applicability of ABC-ELISA and protein A-ELISA in serological diagnosis of cysticercosis. Korean J Parasitol. 1993. 31:49–56.

5. Yong TS, Yeo IS, Seo JH, Chang JK, Lee JS, Kim TS, et al. Serodiagnosis of cysticercosis by ELISA-inhibition test using monoclonal antibodies. Korean J Parasitol. 1993. 31:149–156.

6. Rim HJ, Lee JS, Joo KH, Kim SJ, Won CR, Park CY. Therapeutic Trial Of Praziquantal (Embay 8440; Biltricide(R)) On The Dermal And Cerebral Human Cysticercosis. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi. 1982. 20:169–190.

7. Mohanty A, Das S, Kolluri VR, Das BS. Spinal extradural cysticercosis: a case report. Spinal Cord. 1998. 36:285–287.

8. Sotelo J, Guerrero V, Rubio F. Neurocysticercosis: a new classification based on active and inactive forms. A study of 753 cases. Arch Intern Med. 1985. 145:442–445.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download