Abstract

A coronary artery aneurysm is an uncommon disorder and is seen as a characteristic dilatation of a localized portion of the coronary artery. Clinical manifestation of a coronary artery aneurysm varies from an asymptomatic presentation to sudden death of a patient. Although coronary aneurysms are typically diagnosed by the use of coronary angiography, a new generation of coronary 64-slice multidetector computed tomography (64-MDCT) scanners have successfully been used for evaluating this abnormality in a noninvasive manner. In the present case, we performed coronary 64-MDCT scanning preoperatively and postoperatively on a patient with multiple giant coronary aneurysms. The use of coronary 64-MDCT may provide an evaluation technique not only for diagnosis but also for follow-up after surgery for this condition.

A coronary artery aneurysm is defined as a focal dilatation that exceeds 1.5 times or more the diameter of the adjacent normal coronary artery. It is a rare clinical entity,1 and conventional coronary angiography remains the standard reference technique for the diagnosis of coronary aneurysms. However, it is only valuable for identifying intravascular characteristics that are detected after contrast dye injection and its use provides only limited anatomic information about coronary aneurysms. Recently, the development and utilization of widely performed coronary 64-MDCT provide high quality 2-dimensional and three-dimensional images that allow a precise evaluation of coronary aneurysm size, morphology, location, and the amount of thrombus and calcification.

We present a case of multiple giant coronary aneurysms that presented with angina pain, evaluated by the use of coronary 64-MDCT imaging before and after surgical treatment.

A 66-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and bronchial asthma presented with Canadian Cardiovascular Society Functional Classification Class III angina. One month earlier, the patient was admitted after a transient ischemic attack. Coronary 64-MDCT (Aquilion 64, Toshiba Medical Systems) was performed to define the cardiac mass and evaluate ischemic heart disease. Routine preparation of the patient for coronary 64-MDCT included administration of an oral dose of 75 mg of atenolol 1 hour prior to the examination, when the heart rate was up to 65 beats per minute, and administration of a sublingual dose of nitroglycerin (0.6 mg) prior to scanning.

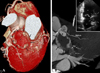

The coronary 64-MDCT showed the presence of three giant aneurysms-2 aneurysms from the left circumflex artery (LCX) and one aneurysm from the ramus intermedius (Fig. 1A). The 2 smaller aneurysms did not show the presence of a gross thrombus (Fig. 1a and 1b). The largest aneurysm was measured 3.0 × 3.5 cm, and was filled with thrombus in an aneurismal sac (Fig. 1c). In addition, 64-MDCT imaging revealed poor wall delineation and reduced blood flow in the distal portion of the vessel. The routine transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed the presence of a round, spherical, and inhomogenous mass (3.20 × 3.10 cm) at the left atrial appendage site (Fig. 1B), accompanied by moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction: 43%) and akinesis of the posterolateral and inferior wall from the base to the apex. The transesophageal echocardiography showed the presence of a round mass compressing the left atrial appendage (3.20 × 3.13 cm) that exhibited well-defined inhomogenous and hyperechogenic characteristics. A subsequent coronary angiography examination also identified the presence of 3 aneurysms: The two smaller aneurysms showed smooth vessel contours and homogenous contrast filling (Fig. 2A and 2B), and the largest aneurysm of the LCX (3.15 × 3.17 cm) showed partial and irregular contrast staining along the vessel wall and the aneurysm was filled with thrombus (Fig. 2C).

A treadmill test was performed, and chest pain was reproduced in the patient. The treadmill test demonstrated 2 mm of ST depression in leads II, III and aVF. We decided to perform surgical revascularization with a surgical resection of the aneurysms, because the patient complained of effort angina. The patient was referred to the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery and underwent coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery with the removal of the aneurysms. Saphenous vein grafts were connected in the distal ramus and distal LCX. The aneurysms were ligated proximally and distally, and were then completely resected. The pathology of the resected aneurysm sac was atherosclerosis with thrombosis. The patient received a follow-up coronary 64-MDCT examination 2 weeks after the CABG. The follow-up 64-MDCT showed no aneurysms present with good vein grafts and blood flow (Fig. 3). A follow-up TTE performed after 6 months demonstrated mild left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction: 47%) and severe hypokinesis of the posterolateral and inferior wall from the base to the apex. The patient received follow-up at the outpatient clinic and presented no angina symptoms.

The incidence of a coronary artery aneurysm is thought to occur in less than 5% of patients, but the reported incidence varies.2 The Coronary Artery Surgery Study Registry reported an angiographic incidence of 4.9% among a group of 20,087 patients.3 Most coronary aneurysms are of atherosclerotic origin, and develop in the native coronary artery adjacent to atheroma. Kawasaki's disease is also an another cause of coronary aneurysms.4 Patients with coronary aneurysms can be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Although the clinical manifestation of a coronary aneurysm is usually asymptomatic, patients may present with angina, myocardial infarction (MI),5 sudden cardiac death,6 and congestive heart failure that can be caused by aneurysm or comorbid coronary artery disease. Rupture of the aneurysm into the pericardium and fistula formation into an adjacent cardiac chamber may rarely occur, however, require prompt surgical intervention.7 The differential diagnosis of a coronary artery aneurysm includes an aneurysm of the myocardium, posttraumatic pseudoaneurysms of the ascending aorta or the pulmonary trunk, a primary tumor of the heart and a thymoma.8 The risk of aneurysm rupture is associated with size, as large aneurysms have more pressure according to Laplace's law.9 Due to the rare occurrence, standard treatment of a coronary aneurysm has not yet been determined. When there is an evidence of ischemia, multiple surgical strategies, including proximal and distal ligation of an aneurysm with coronary artery bypass grafting, aneurysm resection with direct end-to-end anastomosis and reverse saphenous vein interposition grafting, have been performed.10 In addition, endovascular approaches, such as graft stenting and coil embolization, have been introduced.11 Surgical treatment of a coronary aneurysm should be determined by physical characteristics of the aneurysm, including size, presence of a rupture or fistula, and obstruction. The prognosis of a coronary artery aneurysm is associated with the severity of concomitant coronary disease, and no significant difference in survival rate has been noted between cases with and without a coronary artery aneurysm.3 However, an excellent outcome of surgically treated coronary artery aneurysms has been reported in patients with significant coronary stenosis or angina.12

Although coronary angiography is still the gold standard for coronary aneurysm, 64-MDCT may be equivalent or better diagnostic tool, as described in a recent case report.13 The use of 64-MDCT allows more accurate delineation of the size and peculiar shape of an aneurysm than the use of coronary angiography. Furthermore, the use of 64-MDCT provides multiplanar and volumetric images that may be valuable in preoperative decision making by displaying the spatial relationship of the aneurysms, large vessels, and the heart, and also provides information regarding the extent of a thrombus and the extent of luminal blood flow.

In conclusion, 64-MDCT is considered as a useful technique for characterizing the nature and components of coronary aneurysms, and seems to provide reliable anatomical information for both preoperative evaluation as well as postoperative follow-up.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Coronary 64-MDCT scan images (A) and an apical two-chamber view of transthoracic echocardiography (B). Three-dimensional images using the volume rendered technique (left) and curved multi-planar reformation (right) show 3 large aneurysms-1 aneurysm from the ramus intermedius (a) and two aneurysms from the circumflex artery (b and c). The largest aneurysm was measured 3.0 × 3.5 cm (black arrows) and had central low attenuation from the liquefied thrombus (mean CT number of 30 Hounsfield units) (c). The second aneurysm of the left circumflex artery is noted next to the largest aneurysm and shows strong homogenous enhancement (b). The distal circumflex artery shows multiple small saccular dilatations (double arrows). Many small collateral vessels and the vascular bed are less clearly enhanced by contrast material due to slow blood flow (white arrows in A). A round, spherical, and echogenic mass (white arrows of 1B) is seen adjacent to the left atrial appendage. LAD, left anterior descending; LM, left main artery; RCA, right coronary artery; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle.

Fig. 2

A conventional coronary angiographic image at a right anterior oblique-caudal view. Two aneurysms are homogenously enhanced by contrast (A and B). The largest aneurysm shows irregular enhancement in the periphery (black arrows), and most of the central area are filled with thrombus (C). The second aneurysm of the left circumflex artery shows homogenous filling with contrast material (B). Faint contrast staining is noted on the distal side of the largest aneurysm (white arrows). A delayed image might have shown collaterals that were seen on CT angiography. Ra, ramus intermedius; CT, computed tomography.

Fig. 3

Coronary 64-MDCT images after surgical repair of the aneurysms and CABG. Three-dimensional images using the volume rendered technique show 2 free venous grafts connecting the distal ramus (white dotted arrows) and distal circumflex artery (white solid arrows). The aneurysms are no longer seen. Collateral vessels and distal circumflex arteries are better defined after the removal of the aneurysms (black arrows). LM, left main; 64-MDCT, 64-slice multidetector computed tomography; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft.

References

1. Swaye PS, Fisher LD, Litwin P, Vignola PA, Judkins MP, Kemp HG, et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1983. 67:134–138.

2. Ercan E, Tengiz I, Yakut N, Gurbuz A. Large atherosclerotic left main coronary aneurysm: a case report and review of literature. Int J Cardiol. 2003. 88:95–98.

3. Robertson T, Fisher L. Prognostic significance of coronary artery aneurysm and ectasia in the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) registry. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987. 250:325–339.

4. Wong CK, Cheng CH, Lau CP, Leung WH. Asymptomatic congenital coronary artery aneurysm in adulthood. Eur Heart J. 1989. 10:947–949.

5. Chia HM, Tan KH, Jackson G. Non-atherosclerotic coronary artery aneurysms: two case reports. Heart. 1997. 78:613–616.

6. Demopoulos VP, Olympios CD, Fakiolas CN, Pissimissis EG, Economides NM, Adamopoulou E, et al. The natural history of aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Heart. 1997. 78:136–141.

7. Channon KM, Banning AP, Davies CH, Bashir Y. Coronary artery aneurysm rupture mimicking dissection of the thoracic aorta. Int J Cardiol. 1998. 65:115–117.

8. Hinterauer L, Roelli H, Goebel N, Steinbrunn W, Senning A. Huge left coronary artery aneurysm associated with multiple arterial aneurysms. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1985. 8:127–130.

9. Ghanta RK, Paul S, Couper GS. Successful revascularization of multiple coronary artery aneurysms using a combination of surgical strategies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007. 84:e10–e11.

10. Westaby S, Vaccari G, Katsumata T. Direct repair of giant right coronary aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999. 68:1401–1403.

11. Peterson MA, Monsein LH, Dangas G, Mehran R, Leon MB. Percutaneous transcatheter management of giant coronary aneurysms. Circulation. 1999. 100:E8–E11.

13. Khositeseth A, Siripornpitak S, Pornkul R, Wanitkun S. Case report: Giant coronary aneurysm caused by Kawasaki disease: follow-up with echocardiography and multidetector CT angiography. Br J Radiol. 2008. 81:e106–e109.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download