Abstract

Human brucellosis has a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, which includes endocarditis, a focal complication that is uncommon yet responsible for the majority of associated deaths. The most successful treatment outcomes of Brucella endocarditis have been reported with usage of both antimicrobial agents and surgery. However, there are few reports on the treatment of Brucella endocarditis using antibiotics only. We report the first case in Korea of Brucella endocarditis with aortic valve vegetations and an accompanying splenic abscess, which were treated successfully with antibiotic therapy alone.

Human brucellosis is a common zoonotic disease, which affects various organs and has a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations in both humans and animals.1 The infection usually manifests as a febrile syndrome with chills, sweating, arthralgia, and myalgia without an apparent focus.1 Endocarditis is a rare complication of Brucellosis: review of a large series of 1,500 patients with the disease reported only a 0.8% incidence of endocarditis, which is the main cause of morbidity and mortality related to this disease.2

Although the recommended treatment for Brucella endocarditis remains controversial, there is consent that antibiotic therapy should be administered prior to surgery in patients with left ventricular failure caused by severe valvular destruction or a malfunctioning prosthetic valve and those with abscess formation.3 However, patients with short evolution of the disease and mild cardiovascular infection can be treated with antibiotic therapy only.3

The first suspected case of human brucellosis in Korea was that of a livestock worker in 2002.4 Since then, the incidence of human brucellosis has been on the rise. We report the first case of Brucella endocarditis with aortic valve vegetation and an accompanying splenic abscess, which were treated successfully using antibiotic therapy only.

A 45-year-old male patient, who used to work in the livestock industry, was hospitalized with symptoms of fever, chills, sweating, headache, intermittent myalgia and a past month weight loss of 10 kg. He had taken cold medicine, which included acetaminophen, mucolytics and antihistamines, for 2 weeks. He had no past medical history of rheumatic fever or any other heart diseases. His cattle's brucellosis tests from six months ago were all negative; in addition, he stated that he had never ingested any dairy products from his cattle.

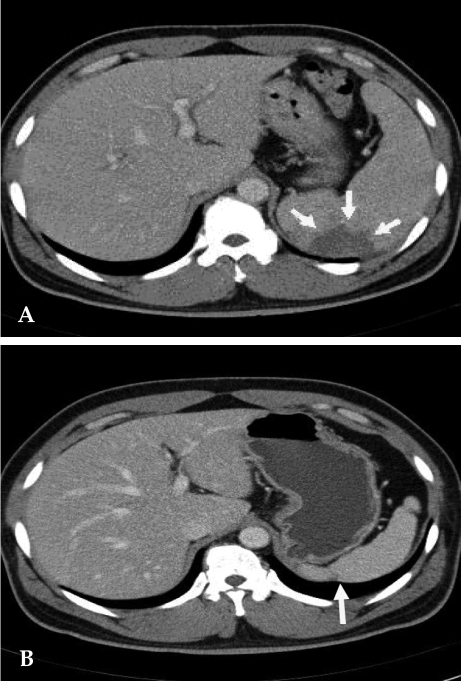

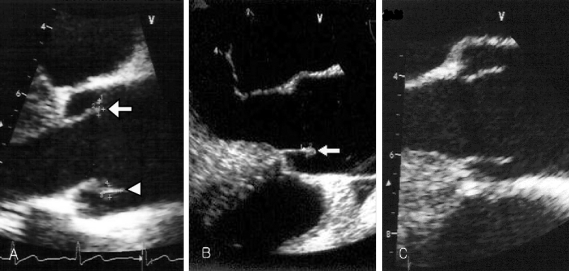

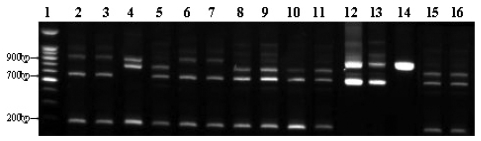

His physical examination showed a body temperature of 38.8℃, blood pressure of 102/80mmHg, and a heart rate of 90 beats/minute. A diastolic murmur of grade 2 was auscultated at Erb's point. Laboratory studies were as follows: hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL, hematocrit 35.65%, leukocyte 5,580/mm3 (granulocyte 51.4%, lymphocyte 40.6%, monocyte 5.5%), platelet 218,000/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 29 mm/hour, C-reactive protein (CRP) 4.31 mg/mL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 56 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 52 IU/L, gamma guanosine triphosphate (γ-GTP) 72 IU/L. All other lab values were normal. Chest X-ray did not show any cardiomegaly or enhanced opacity of pulmonary vasculature. Electrocardiography appeared normal without atrial enlargement, ventricular hypertrophy, ST-T change, or dysrhythmia. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 15.6 cm splenomegaly with a partial wedge shaped splenic abscess (Fig. 1). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed normal left ventricular systolic function. Mild aortic and tricuspid valve regurgitation was present. TTE also revealed an oscillating vegetation on the noncoronary cusp (3 × 5 mm) and right coronary cusp (2 × 4 mm) (Fig. 2). The other echocardiographic parameters were as follows: left ventricular end diastolic dimension (LVEDD), 57 mm, left ventricular end systolic dimension (LVESD), 33 mm, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), 72%, dimension of aortic root, 37 mm, dimension of left atrium, 38 mm, pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP), 31 mmHg, left ventricular septal thickness in diastole (LVSTd), 13 mm, and left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole (LVPWTd), 13 mm. Serum antibody test using standard tube agglutination (STA) upon admission had a positive result as the Brucella serologic titer was over by 1 : 160 dilution (200 IU). Anti-brucella IgG and IgM antibodies by ELISA (PanBio #BAB01M, G, Australia) were also positive (IgM 48, IgG 31). A blood culture test with trypticase soy agar (TSA, containing 5% sheep blood) and BACTEC culture (PEDS plus media) were used to isolate and identify the bacteria causing his symptoms. The genus-specific bcsp31 (223 bp), omp36 (195 bp), and 16s rRNA (905 bp) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) identified all the isolates as Brucella species (Fig. 3). Brucella abortus bv 1 strain was identified by a species-specific associative memory organization system (AMOS)-PCR (Fig. 4).

Gentamycin (160 mg/day, intravenous [IV]), rifampicin (600 mg/day, per os [po]) and doxycycline (200 mg/day, po) were administered. Clinical symptoms started improving beginning the fourth day of treatment and he was discharged on the 16th day. He was followed up in the outpatient department and was given further antibiotic treatment of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (320 mg/1600 mg/day, po), rifampicin (600 mg/day, po) and doxycycline (200mg/day, po). After one month of treatment, ESR and CRP were 9 mm/hour and 0.09 mg/mL respectively. Two months later, follow-up transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed no change in the size of the vegetation on the noncoronary cusp, while that on the right coronary cusp completely disappeared. Seven months later, follow up TEE showed complete resolution of the remaining vegetation. The patient completed the 12 months long drug regimen. Therapy side effects of neutropenia, hepatitis, or skin eruption were not observed. Twelve months later, we followed up with an abdominal CT scan, serological assay, and blood culture. Abdominal CT scan showed a normalized spleen size of about 11 cm compared to the previous splenomegaly size of 15 cm. The partial splenic abscess changed into cortical dimpling with segmental shrinkage without any additional abscess formation (Fig. 1). Follow-up serum antibody test results were STA 1:20 (24 IU); ELISA tests were IgM < 11 and IgG 19 and blood culture tests showed no organisms. The patient has been followed up with control visits and has shown no sign of a recurrence.

Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease that is distributed worldwide, yet still remains endemic in some developing countries. Human brucellosis is usually caused by Brucella melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, and rarely by B. canis.5 Between 2002 and 2006 human brucellosis in Korea showed an incidence of 0.01/100,000 (1 patient) and 0.44/100,000 (215 patients) respectively. B. abortus was the most frequently isolated strain in human cases of brucellosis, reaching some 99% of total cases.6 The incidence of Brucella in the province in which the patient lived was the same as for the Republic of Korea.6 Brucella spp. are usually transmitted from affected animals to humans by ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products and on rare occasions are transmitted by inhalation or by direct animal contact.7 Transmission, however, cannot occur through direct physical contact between humans. Brucellosis develops more frequently in young male patients, especially slaughterhouse workers, farmers, veterinarians, and laboratory workers.7 Human brucellosis is diagnosed using clinical symptoms and signs, serum antibody test, and isolation of Brucella spp. from blood or other tissues. Biotypes are determined by electrophoresis.

Diagnosis of Brucella endocarditis is made by detection of vegetations in an echocardiogram and isolation of Brucella spp. from blood or tissue culture.8 The usually affected valves are aortic and mitral, being aortic the most common.9-12 Although the mortality rate for brucellosis is less than 1%, endocarditis accounts for 80% of these deaths.2 Endocarditis presents with heart failure, acute aortic or mitral valve insufficiency, bradyarrhythmia, cardiac fistula, microabscess within cusps, calcification, or commissure degeneration.9,13,14 Valvular destruction resulting in left ventricular failure is the most common complication. Also septic emboli might cause embolic events in several organs.

Brucella spp. are a homogenous group of gram-negative coccobacilli, which are ingested by cells of the monocyte-macrophage system and can survive and replicate within them.15 This intracellular lifestyle of the organism makes it more difficult to kill using antibiotic therapy. Also, primary treatment of human brucellosis is prone to fail because of an oftentimes delayed diagnosis, the tendency for the disease to recur, and its chronic clinical course. Human brucellosis usually has a severe progression, thus early diagnosis is crucial for adequate treatment. The treatment regimen and duration for Brucella endocarditis are not yet established. The therapeutic approach for Brucella endocarditis traditionally involved the combination of medical and surgical treatment,10,16,17 with significant mortality reduction.14 When there are signs of left ventricular failure due to severe valvular destruction or dysfunction of the prosthetic valve, valvular abscess formation or a life-threatening embolic event, surgery is deemed necessary after attempting to stabilize the patient first by medical treatment. In those conditions, medical treatment cannot be adequate, if used alone. But if the clinical course is short: less than 2 months, and shows mild heart involvement without left ventricular failure, treatment with antibiotics alone may be attempted.18 There have been occasional reports on previous cases of complete remission with medical treatment alone.2,18-20 Reguera et al. reported that the triple combination of streptomycin for the first three weeks, followed by doxycycline and rifampicin without surgery for the next three months showed successful treatment in a Brucella endocarditis patient.18 Three out of eleven patients with Brucella endocarditis received only medical treatment, with favorable results. Early surgical treatment was undertaken in the other eight patients. Mert et al. used a triple antibiotics combination regimen of doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for four months with satisfactory clinical results.2 In our case, there was a splenic abscess resulting from septic emboli, but it was not life-threatening. An abdominal CT scan revealed the small area of very early splenic abscess formation that did not have a liquid component, which thereby could not be drained. Clinical manifestations such as fever and chills improved very quickly; ESR and CRP decreased rapidly. Therefore, drainage or splenectomy was not performed. Also the evolution was short without left ventricular failure, which made medical treatment alone a successful therapy. There seems to be unanimous agreement that the treatment period of Brucella endocarditis should be prolonged compared to Brucellosis without complications. As demonstrated in a previously published report of Brucella endocarditis,2 regimen and duration of antibiotic therapy may differ among various centers, depending upon clinical behaviour of the patients.

We treated the patient with antibiotic therapy for twelve months to prevent relapse, with complete resolution of the valvular vegetation without ever using surgery. We decided to prolong the duration of the drug regimen since medical treatment was our main and only mode of therapy. We used gentamicin, rifampicin, and doxycycline for the first month, followed by a triple combination of antibiotics including trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, rifampicin, and doxycycline for 11 months as outpatient medications. The treatment response was quite good showing no side effects, disappearance of the valvular vegetation and splenic abscess, and no illness relapses.

Nevertheless, until now, antibiotic treatment alone in Brucella endocarditis has been reported in isolated cases (in 14 adult patients) in literature2 and neither the combination of drugs nor duration of treatment is well established. As we have seen in our case, with select patients and disease presentations, the option of medical therapy alone may be considered as an equally effective alternative to the medical-surgical strategy. Further prospective studies are required to establish a treatment guideline to the various forms of Brucella endocarditis.

References

1. Young EJ. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Brucella species. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 2000. 5th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone;p. 2386–2391.

2. Mert A, Kocak F, Ozaras R, Tabak F, Bilir M, Kucukuglu S, et al. The role of antibiotic treatment alone for the management of Brucella endocarditis in adults: a case report and literature review. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002; 8:381–385. PMID: 12517300.

3. Memish Z, Mah MW, Al Mahmoud S, Al Shaalan M, Khan MY. Brucella bacteraemia: clinical and laboratory observations in 160 patients. J Infect. 2000; 40:59–63. PMID: 10762113.

4. Park MS, Woo YS, Lee MJ, Shim SK, Lee HK, Choi YS, et al. The first case of human brucellosis in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2003; 35:461–466.

5. Peery TM, Belter LF. Brucellosis and heart disease. II. Fatal brucellosis: a review of the literature and report of new cases. Am J Pathol. 1960; 36:673–697. PMID: 14431371.

6. KCDC. Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. CDWR. 2006; 52:1–36.

7. Young EJ. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Brucella species. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 1995. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone;p. 2053–2060.

8. Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med. 1994; 96:200–209. PMID: 8154507.

9. Delvecchio G, Fracassetti O, Lorenzi N. Brucella endocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 1991; 33:328–329. PMID: 1743797.

10. al-Mudallal DS, Mousa AR, Amin Marafie AA. Apyrexic Brucella melitensis aortic valve endocarditis. Trop Geogr Med. 1989; 41:372–376. PMID: 2635455.

11. Caldarera I, Albanese S, Piovaccari G, Ferlito M, Galli R, Squadrini F, et al. Brucella endocarditis: role of drug treatment associated with surgery. Cardiologia. 1996; 41:465–467. PMID: 8767636.

12. Kumar N, Prabhakar G, Kandeel M, Mohsen IZ, Awad M, al-Halees Z, et al. Brucella mycotic aneurysm of ascending aorta complicating discrete subaortic stenosis. Am Heart J. 1993; 125:1780–1782. PMID: 8498327.

13. al-Harthi SS. The morbidity and mortality pattern of brucella endocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 1989; 25:321–324. PMID: 2613379.

14. Fernández-Guerrero ML. Zoonotic endocarditis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1993; 7:135–152. PMID: 8463649.

15. Young EJ. An overview of human brucellosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995; 21:283–289. quiz 290. PMID: 8562733.

16. Bayer AS, Bolger AF, Taubert KA, Wilson W, Steckelberg J, Karchmer AW, et al. Diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis and its complications. Circulation. 1998; 98:2936–2948. PMID: 9860802.

17. Arslan H, Korkmaz ME, Kart H, Gül C. Management of brucella endocarditis of a prosthetic valve. J Infect. 1998; 37:70–71. PMID: 9733385.

18. Reguera JM, Alarcón A, Miralles F, Pachón J, Juárez C, Colmenero JD. Brucella endocarditis: clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic approach. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003; 22:647–650. PMID: 14566576.

19. Flugelman MY, Galun E, Ben-Chetrit E, Caraco J, Rubinow A. Brucellosis in patients with heart disease: when should endocarditis be diagnosed? Cardiology. 1990; 77:313–317. PMID: 2073648.

20. Micozzi A, Venditti M, Gentile G, Alessandri N, Santero M, Martino P. Successful treatment of Brucella melitensis endocarditis with pefloxacin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990; 9:440–442. PMID: 2387299.

Fig. 1

(A) Contrast-enhanced abdomen CT scan reveals partial splenic abscess that is a wedge shape (arrow) and splenomegaly. (B) Twelve months later, follow-up CT scan reveals normalized spleen size of about 11 cm compared with the previous splenomegaly size of 15 cm. A portion of the splenic abscess changed into cortical dimpling (arrow) with segmental shrinkage.

Fig. 2

(A) Transesophageal echocardiography reveals one vegetation (4 × 2 mm, arrow) on the right aortic coronary cusp and the other vegetation (5 × 3 mm, arrow head) on the noncoronary aortic cusp upon admission. (B) Two months later, follow up transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) reveals no interval change of the vegetation (arrow) size within the noncoronary cusp, but vegetation within the right coronary cusp was completely resolved. (C) Seven months later, follow up TEE shows complete resolution of the remained vegetation.

Fig. 3

Genus-specific PCR. Molecular diagnostic assays based on PCR amplification of different genomic targets for the identification of Brucella spp. tested of the isolate. The clinical isolate was tested by the conventional biochemical tests and detected with common genes (BCSP-31 kDa, OMP2-36kDa, 16S rRNA) of Brucella spp. M, 100 bp marker; Lane 1, Brucella abortus ATCC 2308; Lane 2, Patient's isolate.

Fig. 4

Species-specific AMOS-Multi-PCR. We have adopted Multiplex AMOS-PCR method for the species-specific typing of clinical isolate. In the profile of Multiplex AMOS-PCR, B. abortus (biovar 1, 2, 3, 4, 6), B. melitensis (biovar 1, 2), B. canis, and B. suis (biovar 3) showed characterization patterns into the respective species and four different amplification patterns were observed. Multiplex AMOS-PCR patterns I (200, 600 and 900 bp) were B. melitensis (biovar 1, 2), B. abortus (biovar 3, 6), patterns II (200, 600 and 720 bp) were B. abortus (biovar 1, 2, 4), patterns III (600 and 900 bp) were B. canis, B. suis (biovar 3) and patterns IV (200, 720 and 900 bp) were B. abortus ATCC 7705. The clinical isolate of our patient had identical patterns as B. abortus biovar 1 (patterns II). Lane 1, 100 bp ladder; Lane 2 & 3, B. melitensis; Lane 4, B. abortus ATCC 7705; Lane 5, B. abortus bv.1; Lane 6, B. abortus bv. 3; Lane 7, B. abortus bv.6; Lane 8, B. abortus bv.2; Lane 9, B. abortus bv4; Lane 10, S19; Lane 11, RB51; Lane 12, B. canis; Lane 13, B. suis; Lane 14, B. ovis; Lane 15, other patient's isolate (B. abortus bv.1); Lane 16, our patient's isolate.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download