1. Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN. Breast cancer in men. Ann Intern Med. 2002. 137:678–687.

2. Giordano SH, Cohen DS, Buzdar AU, Perkins G, Hortobagyi GN. Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study. Cancer. 2004. 101:51–57.

3. The Korean Breast Cancer Society. Nationwide Korean breast cancer data of 2004 using breast cancer registration program [In Korean]. J Breast Cancer. 2006. 9:151–161.

4. Son BH, Kwak BS, Kim JK, Kim HJ, Hong SJ, Lee JS, et al. Changing patterns in the clinical characteristics of Korean patients with breast cancer during the last 15 years. Arch Surg. 2006. 141:155–160.

5. Cho J, Han W, Ko E, Lee JW, Jung SY, Kim EK, et al. The clinical and histopathological characteristics of male breast cancer patients [In Korean]. J Breast Cancer. 2007. 10:211–216.

6. Malani AK. Male breast cancer: a different disease than female breast cancer? South Med J. 2007. 100:197.

7. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006. 56:106–130.

8. Contractor KB, Kaur K, Rodrigues GS, Kulkarni DM, Singhal H. Male breast cancer: is the scenario changing. World J Surg Oncol. 2008. 6:58.

9. Sasco AJ, Lowenfels AB, Pasker-de Jong P. Review article: epidemiology of male breast cancer. A meta-analysis of published case-control studies and discussion of selected aetiological factors. Int J Cancer. 1993. 53:538–549.

10. Carlsson G, Hafström L, Jönsson PE. Male breast cancer. Clin Oncol. 1981. 7:149–155.

11. Hill TD, Khamis HJ, Tyczynski JE, Berkel HJ. Comparison of male and female breast cancer incidence trends, tumor characteristics, and survival. Ann Epidemiol. 2005. 15:773–780.

12. Lee DH, Kim JH, Nam JJ, Kim HR, Shin HR. Epidemiological findings of hepatitis B infection based on 1998 National Health and Nutrition Survey in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2002. 17:457–462.

13. Ioka A, Tsukuma H, Ajiki W, Oshima A. Survival of male breast cancer patients: a population-based study in Osaka, Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006. 36:699–703.

14. Matsuno RK, Anderson WF, Yamamoto S, Tsukuma H, Pfeiffer RM, Kobayashi K, et al. Early- and late-onset breast cancer types among women in the United States and Japan. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007. 16:1437–1442.

15. Nahleh Z, Girnius S. Male breast cancer: a gender issue. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006. 3:428–437.

16. Agrawal A, Ayantunde AA, Rampaul R, Robertson JF. Male breast cancer: a review of clinical management. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007. 103:11–21.

17. Chung HC, Koh EH, Roh JK, Min JS, Lee KS, Suh CO, et al. Male breast cancer-a 20-year review of 16 cases at Yonsei University. Yonsei Med J. 1990. 31:242–250.

18. Giordano SH. A review of the diagnosis and management of male breast cancer. Oncologist. 2005. 10:471–479.

19. Meguerditchian AN, Falardeau M, Martin G. Male breast carcinoma. Can J Surg. 2002. 45:296–302.

20. Donegan WL, Redlich PN, Lang PJ, Gall MT. Carcinoma of the breast in males: a multiinstitutional survey. Cancer. 1998. 83:498–509.

21. Ko KH, Kim EK, Park BW. Invasive papillary carcinoma of the breast presenting as post-traumatic recurrent hemorrhagic cysts. Yonsei Med J. 2006. 47:575–577.

22. Thomas DB, Jimenez LM, McTiernan A, Rosenblatt K, Stalsberg H, Stemhagen A, et al. Breast cancer in men: risk factors with hormonal implications. Am J Epidemiol. 1992. 135:734–748.

23. Volpe CM, Raffetto JD, Collure DW, Hoover EL, Doerr RJ. Unilateral male breast masses: cancer risk and their evaluation and management. Am Surg. 1999. 65:250–253.

24. Crew KD, Neugut AI, Wang X, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Raptis G, et al. Racial disparities in treatment and survival of male breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007. 25:1089–1098.

25. Guénel P, Cyr D, Sabroe S, Lynge E, Merletti F, Ahrens W, et al. Alcohol drinking may increase risk of breast cancer in men: a European population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2004. 15:571–580.

26. Weiss JR, Moysich KB, Swede H. Epidemiology of male breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005. 14:20–26.

27. Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN. Male breast cancer. Lancet. 2006. 367:595–604.

28. Ribeiro GG, Swindell R, Harris M, Banerjee SS, Cramer A. A review of the management of the male breast carcinoma based on an analysis of 420 treated cases. Breast. 1996. 5:141–146.

29. Giordano SH, Perkins GH, Broglio K, Garcia SG, Middleton LP, Buzdar AU, et al. Adjuvant systemic therapy for male breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005. 104:2359–2364.

30. Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, Buzdar A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 year' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005. 365:60–62.

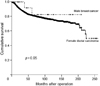

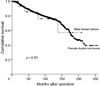

31. Willsher PC, Leach IH, Ellis IO, Bourke JB, Blamey RW, Robertson JF. A comparison outcome of male breast cancer with female breast cancer. Am J Surg. 1997. 173:185–188.

32. The Korean Breast Cancer Society. Survival analysis of Korean breast cancer patients diagnosed between 1993 and 2002 in Korea-a nationwide study of the cancer registry [In Korean]. J Breast Cancer. 2006. 9:214–229.

33. Lee WS, Lee JE, Kim JH, Nam SJ, Yang JH. Analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modality changes in breast cancer: a single institution study in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2007. 48:465–473.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download