Abstract

Purpose

The reliability and validity of a Korean version of the Obsessive-Compulsive-Inventory-Revised (OCI-R) was examined in non-clinical student samples.

Materials and Methods

The Korean version of OCI-R was administered to a total of 228 Korean college students. The Maudsley Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (MOCI), Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI), and Beck's Anxiety Inventory (BAI) were administered to 228 students.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is manifested by a diverse groups of symptoms that include intrusive thoughts, rituals, preoccupations and compulsions.1 The lifetime prevalence of OCD is estimated at 2.5 percent in the general population,2 and 0.4 to 2.3 percent in Korean population.3 The causes of OCD are still unclear, but there is growing evidence that OCD has some neurobiological bases. In addition, familial, twin and segregation studies support the role of a genetic component in the etiology of OCD.4,5 The obsessions or compulsions cause severe psychological and behavioral distress to patients which may result in impairments in social, occupational functioning and interpersonal relationships. Patients with OCD usually think their symptoms shameful, so they try not to expose their symptoms to others.6 Even though patients with OCD are distressed with obsessions or compulsions which are time-consuming and significantly interfere with the person's normal routine, occupational functioning, usual social activities or relationships, they are seldom referred to hospital because their cognitive functions and judgments are preserved, thus making them appear normal. As patients with OCD are likely to be misdiagnosed or undiagnosed, it is important to properly screen patients and provide a correct diagnosis to provide them with proper treatment.

Proper tools are needed to make early and correct diagnosis for OCD. Diagnostic tools involve clinical interview by clinician, behavior observation (by self or others) and self-report questionnaires. Among these, self-report questionnaires are found to be the most economic and easiest to administer, and there are many self-report questionnaires developed and used in clinical practice and research fields. New questionnaires have recently been developed to overcome limitations of their predecessors, particulary their insufficient coverage of all types of OCD symptoms. These include the Maudsley Obsessive compulsive Inventory,7 Padua Inventory,8 Vancouver Obsessive Compulsive Inventory,9 Leyton Obsessional Inventory,10 and Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory.11 Each questionnaire has several limitations. The MOCI, for example, has not been reported to be internally consistent nor factorially distinct, and coverage of OCD symptoms other than washing and checking (e.g. hoarding, convert rituals) is limited. The MOCI is also not suitable for measuring changes with treatment, both because of its dichotomous response format and of several items referred to past and permanent events.12,13 For the PI, it has been reported that several items were found to measure worry rather than obsessions, and it does not encompass certain categories of obsession and compulsions, including neutralizing and hoarding.14 The LOI is less applicable to clinical OCD than to subclinical symptoms, because it was developed for homemakers rather than OCD patients, and is insensitive to symptom reductions that are evident in other measures.15 The OCI consists of 42 items grouped in 7 subscales (checking, washing, obsessing, mental neutralizing, ordering, hoarding, and doubting), measured on two 5-point Likert scales of symptom frequency and associated distress. The OCI shows sound psychometric properties in both clinical11 and non-clinical samples.16 However, since frequency and distress scales of the questionnaire seemed to be redundant, and a revised and shortened version was developed in order to make the administration easier.

The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R)17 is a shortened version of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory that measures OCD symptoms. The OCI-R consists of 18 items and provides a total score and scores on six subscales: washing, checking, ordering, obsessing, hoarding, and neutralizing. The psychometric properties of the OCI-R showed good to excellent internal consistency, test-retest reliability and convergent validity in both clinical and nonclinical samples.17 It showed a good ability to discriminate between patients with OCD and other anxiety groups, with exceptions of its hoarding and ordering subscales. The following studies addressed the psychometric properties of the OCI-R in a student population.18 Six factors were confirmed in a factor analysis, and the OCI-R showed good convergent and divergent validity in one study.17 The psychometric properties of Spanish version of the OCI-R were also examined in a college student sample.19 Confirmatory factor analysis replicated the original six-factor structure, and the total and each of the subscales of the Spanish OCI-R demonstrated moderate to good internal consistency and convergent validity and good divergent validity. Recently the Icelandic version of the OCI-R demonstrated strong psychometric properties in a student population.20

Individuals with OCD show a considerable amount of heterogeneity and diversity of symptom contents. In addition, diagnostic differentiation from other mental disorders is often difficult, and comorbidity with other mental disorders is high, in particular with major depression and other anxiety disorders.21 The divergent validity of the OCI-R with measures of other kinds of psychopathology needs further exploration, particularly in clinical samples. A poor divergent validity with measures of depression, anxiety and worry has been a substantial shortcoming of OCD measures, and has commonly been attributed to a true symptom overlap between symptoms of OCD, other anxiety disorders, and major depression.22 Potential symptom overlap between obsessions and pathological worry has been reported.23,24 There was a high correlation (r = 0.70) between the OCI-R total score and the Beck Depression Inventory25 total score in a mixed sample of patients with OCD and non-clinical controls. Foa et al. suggest that the high correlations between OCD and depression may reflect high levels of depression observed in OCD patients.17

The goal of this study was to provide Korean version of OCI-R and examine its psychometric properties and factor structure in a sample of college students.

The sample consisted of 228 undergraduate students (85 female and 143 male) from Yonsei University in Korea. Ethical approval for all study methods was obtained from the university ethical committee. Those who have mental or medical illness were excluded from the study. Participation was voluntary and no payment or course credits were offered to the participants. The mean age was 22.5 ± 1.0 years. A subsample of 122 students (50 female and 72 male) were administered self-report measures 10 days later and they constituted for test-retest reliability.

As described above, the OCI-R17 is a 18-item self-administered questionnaire that assess the distress associated with obsessions and compulsions. There are 6 subscales, each with 3 items: washing, checking/doubting, obsessing, mental neutralizing, ordering and hoarding. The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale between 0 and 4. The English version of the OCI-R was translated to Korean each by 2 residents at the Department of Psychiatry. We made a primary translated edition of OCI-R by reviewing 2 of them. The primary translated edition of OCI-R was then back-translated by an another Korean psychiatrist. The primary translated edition and back-translated edition of OCI-R were supervised by an another Korean psychiatrist who was fluent in English. Finally, the Korean version of OCI-R was completed with supervision by Korean language professor.

The Korean version26 of Maudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory7 is a 30-item questionnaire that assess the obsessive compulsive symptoms. It is composed of dichotomous response format, and scores ranged from 0 to 30. The subscales are cleaning, checking, doubting/conscientiousness and obsessional slowness. Korean version has shown to have good internal consistency, good test-retest reliability and good discriminant, and convergent validity.26

The BDI25 is a well-performing, 21 item, self-report questionnaire designed to assess and evaluate the frequency of depressive symptoms over 1-week period. Score ranges from 0 to 64. The Korean version27 of the BDI has demonstrated good reliability and validity in both non-clinical and clinical samples. The internal consistency coefficient of the Korean version of BDI was 0.92.

The BAI29 is a well-performing, 21-item, self-report questionnaire designed to assess and evaluate the frequency of anxiety symptoms over a 1 week period. Score ranges from 0 to 63. We administered a Korean version28 of the BAI, and it demonstrated good psychometric properties. The internal consistency coefficient of the Korean version of the BAI was 0.93, with test-retest reliability at r = 0.84.

All participants were administered the questionnaires in a group setting during a lecture period. A brief description of the purpose of the study was given, and written consent was obtained. The self report questionnaires which contained OCI-R-K, MOCI-K, BDI-K and BAI-K were administered to 350 Korean college student participants. From this pool of subjects, 228 participants (male = 143, female = 85) had usable data for the current study. All of them were administered the same self-report measures 10 days later. A subset of 122 participants (male = 72, female = 50) completed a second administration of the questionnaires and constituted the sample for test-retest reliability.

Statistical analysis were performed using SPSS ver. 12.0. Significance level was set at p < 0.01. Continuius variables in male and female participants were using t-test. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed using AMOS version 5.0. Pearson'r correlation method was used for correlations among the scales, convergent validity, divergent validity and test-retest reliability. We used Cronbach's α to explore internal consistency.

Participants were college undergraduates composed of 143(62.3%) male and 85(37.3%) female students. The mean age was 22.5 ± 1.9. The mean education year was 15.1 ± 1.4. The total score of BDI-K and BAI-K were 5.8 ± 5.6 and 6.0 ± 6.6, respectively, which showed very low levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms.

We conducted a confirmatory analysis using AMOS 5.0 in SPSS version 12.0. We evaluated the fit of our data to the original sis factor structure,17 using the maximum likelihood estimation method. To facilitate comparability, we considered the same fit indices used by Foa et al.17 and Hajcak et al.18 The model had a significant χ²[χ²(120) = 205.32, p < 0.0001], a Goodness-of fit Index (GFI) of 0.91, a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.95, a root-mean-square residual (RMR) of 0.05, and a root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.06. Considering criteria30 by Hu and Bentler (adequate fit indices are GFI and CFI of 0.90 or greater, and RMR and RMSEA values of 0.06 or lower) our results indicated a good fit for the six-factor model, with values similar to those presented by Hajcak et al.18 We also tested a one-factor model, and most indices suggested a poor fit as in Hajcak et al. (χ²(135) = 450.93, p < 0.0001; GFI = 0.805; CFI = 0.80; RMR = 0.08; RMSEA = 0.10).

Based on the above results, therefore we used the original subscales developed by Foa et al.17 in all subsequent analysis.

Cohen's criteria31 were used to evaluate the size of the correlations. Correlations > 0.50 were defined as "large", from 0.30 to 0.49 as "medium", and from 0.10 to 0.29 as "small". Correlations between each of the subscales and the total scale for the OCI-R-K were found to be large (ranging between 0.73 and 0.84), but inter-correlations among the subscales were medium to large (ranging between 0.35 and 0.66) (Table 1).

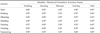

Cronbach's α was calculated and used to assess the internal consistency of the OCI-R-K total and subscale scores. Table 2 shows means, standard deviation and p value for the total OCI-R-K and each of its subscales. Internal consistency for the full scale of the OCI-R was excellent (α = 0.90) and was acceptable for all of the subscales α = 0.70 - 0.79). As in previous studies of both the OCI-R17,18 and the OCI,11 the neutralizing subscale had the lowest alpha, which in our study was same as obsessing subscale in our study. In terms of gender differences, men scored significantly higher than women on the obsessing subscale (3.10 ± 2.55 vs. 1.95 ± 2.68; p = 0.00) subscale.

The obsessing subscale consists of 3 items: "I find it difficult to control my own thoughts.", "I am upset by unpleasant thoughts that come into my mind against my will.", "I frequently get nasty thoughts and have difficulty in getting rid of them." Among these 3 items, there was no significant difference between men and women except the "nasty thoughts" (item 18), where men scored 4 times significantly higher than women (1.05 ± 0.97 vs. 0.27 ± 0.56; p = 0.01).

To assess test-retest reliability between the administrations, Pearson's r was calculated. Our results for the OCI-R total score (0.81) were higher than those of Hajcak et al.18 and Fullana et al.19 (0.70 and 0.67) after one month interval. The OCI-R-K subscale scores were somewhat smaller, but higher than 0.62, showing good test-retest reliability.

OCI-R-K total and subscale score were correlated with scores on the MOCI-K to assess its convergent validity (Table 3). The OCI-R-K total score showed large correlation with the MOCI-K total score (r = 0.60, p < 0.01), indicating good convertgent validity. The washing and checking subscales of the OCI-R-K correlated better with the corresponding cleaning and checking scales of the MOCI-K, respectively, than with other non-corresponding subscales, indicating adequate convergent validity.

The correlation between the total and subscale scores of OCI-R-K, BDI-K and BAI-K scores were small to medium except the obsessing subscale of OCI-R-K, suggesting adequate discriminant validity of the OCI-R-K (Table 4). It was very similar to previous studies by Hajcak et al.18 and Fullana et al.,19 showed that had the highest correlations with the BDI-K. There is a well-known potential symptom overlap between obsessions and pathological worry.23,24 Furthermore, Foa et al.17 found a high correlation (r = 0.70) between the OCI-R and Beck Depression Inventory, as mentioned above. The highest correlation between obsessing subscale of OCI-R-K and BDI-K can be explaned by the relationship between depressive rumination and obsession.18

The psychometric properties of newly developed Korean version of the OCI-R were investigated in a college student population. Our factor-analytic findings confirmed the original17 6-factor structure. For the total and subscales of the OCI-R-K scale, excellent internal consistency was found, which was higher than for the original vergion of the OCI-R previously employed by Foa et al.17 and Hajcak et al.18 The neutralizing and obsessing subscale had the lowest alphas, in agreement with previous studies. The test-retest reliability of the Korean version of the OCI-R scale was higher than those by Hajcak et al.18 and Fullana et al.19 The convergent validity of the Korean version of the total and subscales scores of the OCI-R scale was moderate compared with MOCI-K scale, with moderate divergent validity as well. The washing and checking subscales of the OCI-R-K correlated better with the corresponding cleaning and checking scales of the MOCI-K, respectively, than with other non-corresponding subscales, indicating adequate convergent validity. The divergent validity of the Korean version of OCI-R scale was adequate and similar to previous studies.13,14

Differences among genders were slight, with men scoring higher than women on the obsessing subscale, because of higher rates of endorsement of item 18("I frequently get nasty thoughts and have difficulty in getting rid of them"). On this item, men scored about 4 times higher than women. Fullana et al.19 reported that men reported significantly higher subscale scores than women on the hoarding and checking subscales, which was not found in our results. The gender difference shown in the OCI-R subscales may be due to cultural differences. It is highly possible that Korean men suffer more from recurrent sexual thoughts than women. However, Koreans are strongly influenced by Confucianism for a long time, therefore it may be more reasonable to except that tattoos in sexual expression by Korean women affect the result.

There were several limitations in this study. First, the subjects were highly educated and their average age was in early 20s, therefore, it is difficult to state that the subjects represent general population. Therefore, more studies with various groups should be replicated. Second, subjects of Korean version of OCI-R constituted a non-clinical sample. To ascertain its ability to discriminate OCD from other types of anxiety and depression, the psychometric properties of the Korean OCI-R need to be further examined in clinical samples.

In summary, the Korean version of the OCI-R seems to retain the sound psychometric properties of its original version. Further research is needed, nevertheless, it appears to be an excellent instrument for assessment of obsessive compulsive symptoms in a Korean population.

Figures and Tables

Table 2

Means, Standard Deviations and Internal Consistency (Cronbach's α) for the OCI-R-K Total Scale and Subscales, for the Whole Sample and by Gender

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 2000. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press.

2. Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA. The epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988. 45:1094–1099.

3. Lee CK. A nationwide epidemiological study of mental disorders in Korea. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998. 52 Suppl:S268–SS74.

4. Kim SJ, Kim CH. The genetic studies of obsessive-compulsive disorder and its future directions. Yonsei Med J. 2006. 47:443–454.

5. Kim SJ, Kim YS, Kim CH, Lee HS. Lack of association between polymorphisms of the dopamine receptor D4 and dopamine transporter genes and personality traits in a Korean population. Yonsei Med J. 2006. 47:787–792.

6. Thomsen PH. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: pharmacological treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000. 9:76–84.

7. Sanavio E, Vidotto G. The Components of the Maudsley Obsessional-Compulsive Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1985. 23:659–662.

9. Thordarson DS, Radomsky AS, Rachman S, Shafran R, Sawchuk CN, Ralph Hakstian A. The Vancouver Obsessional Compulsive Inventory (VOCI). Behav Res Ther. 2004. 42:1289–1314.

11. Foa EB, Kozak MJ, Salkovskis PM, Coles ME, Amir N. The validation of a new obsessive-compulsive disorder scale: the obsessive-compulsive inventory. Psychol Assess. 1998. 10:206–214.

12. Emmelkamp PM, Kraaijkamp HJ, van den Hout MA. Assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Modif. 1999. 23:269–279.

13. Taylor S, Thordarson DS, Söchting I. Antony MM, Barlow DH, editors. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Handbook of assessment and treatment planning for psychological disorders. 2004. New York: The Guilfore Press;182–214.

14. Freeston MH, Ladouceur R, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Gagnon F, Thibodeau N. Self report of obsessions and worry. Behav Res Ther. 1994. 32:29–36.

15. Stanley MA, Prather RC, Beck JG, Brown TC, Wagner Stanley, Davis ML. Psychometric analyses of the Leyton Obsessional Inventory in patients with obsessive-compulsive and other anxiety disorders. Psychol Assess. 1993. 5:187–192.

16. Wu KD, Watson D. Further investigation of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: psychometric analysis in two non-clinical samples. J Anxiety Disord. 2003. 17:305–319.

17. Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, et al. The Obsessive-compulsive Inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess. 2002. 14:485–495.

18. Hajcak G, Huppert JD, Simons RF, Foa EB. Psychometric properties of the OCI-R in a college sample. Behav Res Ther. 2004. 42:115–123.

19. Fullana MA, Tortella-Feliu M, Caseras X, Andión O, Torrubia R, Mataix-Cols D. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Obsessive-compulsive Inventory-revised in a non-clinical sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2005. 19:893–903.

20. Smári J, Olason DT, Eypórsdóttir A, Frölunde MB. Psychometric properties of the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised among Icelandic college students. Scand J Psychol. 2007. 48:127–133.

21. Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001. 110:585–599.

22. Taylor S. Swinson RP, Antony MM, Rachman S, Richter MA, editors. Assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Obsessive-Compulsive disorder: theory, research, and treatment. 1998. New York: The Guilford Press;229–257.

23. Abramowitz JS, Foa EB. Worries and obsessions in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1998. 36:695–700.

24. Holaway RM, Heimberg RG, Coles ME. A comparison of intolerance of uncertainty in analogue obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2006. 20:158–174.

25. Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol. 1984. 40:1365–1367.

26. Min BB, Won HT. Reliability and Validity of the Korean translations of Maudsley Obsessional-Compulsive Inventory and Padua Inventory. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1999. 18:163–182.

27. Lee YH, Song JY. A Study of the reliability and the Validity of the BDI, SDS, and MMPI-D Scales. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1991. 10:98–118.

28. Kwon SM. Assessment of psychopathology in anxiety disorder. Korean J Psychopathol. 1997. 6:37–51.

29. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988. 56:893–897.

30. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Model. 1999. 6:1–55.

31. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 1988. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download