Abstract

A hitherto unrecognized variant of solid-pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) of the pancreas is reported. The tumor presented in the pancreatic tail of a 44-year-old female patient. It was a well-defined, solid nodule measuring 25 mm in diameter, with homogenous tan gray cut surface. Histologically, the neoplasm was mostly composed of sheets of spindle cells. No cellular atypia and mitosis was identified. The periphery of the tumor showed typical feature of SPT. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for vimentin, CD10, CD56, β-catenin, and α1-antichymotrypsin, but negative for cytokeratin, chromogranin, synaptophysin and S-100 protein. Ultrastructurally, the tumor showed a few acinar spaces with microvilli between tumor cells. This case is peculiar in that the tumor did not show gross cystic change and predominantly consists of spindle shaped tumor cells, so may cause difficult diagnostic problem.

Solid-pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas usually present as large, hemorrhagic, and cystic masses that are mainly composed of polygonal cells, and they characteristically exhibit prominent cystic change.1 The present case was small in size and no gross cystic change was identified. The tumor was composed predominantly of spindle cells, causing a diagnostic problem. Here, we report an unusual spindle cell variant solid-pseudopapillary tumor with emphasis of differential diagnosis.

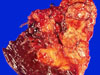

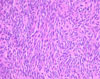

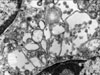

A 44-year-old female patient was admitted due to an incidentally found abdominal mass. She did not complain of any specific symptoms. Pancreatic computed tomography showed a lobulated soft tissue mass at the pancreatic tail. Radiologic impressions included solid-pseudopapillary tumor, non-functioning endocrine tumor, and pancreatic cancer. Distal pancreatectomy was done. Resected pancreatic tumor (2.5 cm in size) was grossly well-defined, homogenous, and soft (Fig. 1), and mostly composed of sheets of spindle cells microscopically (Fig. 2). The spindle cells have scanty cytoplasm and contain regular nuclei with a fine chromatin pattern but no nucleoli. No cellular atypia and mitosis were identified. Focally, the tumor cells are ovoid in shape. The periphery of the tumor showed focally cystic change and pseudopapillary formations (less than 10% of the tumor), which are typical of solid-pseudopapillary tumors (Figs. 3A and B). Occasionally, the tumor showed small hyaline globules. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for vimentin, but negative for cytokeratin, chromogranin, synaptophysin, and S-100 protein. The tumor cells were focally positive for α1-antichymotrypsin. Most of the tumor cells showed nuclear and cytoplasmic positivities for β-catenin (Fig. 4A) and cytoplasmic staining for CD10 (Fig. 4B) and CD56. These immunohistochemical results were similar between the spindle cell area and area of pseudopapillary formation. Ultrastructurally, there were a few zymogen-type granules and neurosecretory granules, and the tumor showed a few acinar spaces with microvilli between tumor cells (Fig. 5). At the time of this report, the patient was still alive with no specific symptoms (18 months after operation).

Solid-pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas are low-grade malignant epithelial tumors2 and consist of monomorphous cells variably expressing epithelial, mesenchymal, and endocrine markers.1 Grossly, they present as large, round, solitary masses (range: 3 - 18 cm) that are usually well demarcated from the remaining pancreas. The cut surface of the tumors reveals lobulated, light brown solid areas admixed with zones of hemorrhage and necrosis as well as cystic spaces filled with necrotic debris.3,4 However, cystic changes can be less prominent in smaller tumors.5 Histologically, the tumors exhibit a solid monotonous pattern with sclerosis and a pseudopapillary pattern. In both patterns, uniform polygonal cells are arranged around delicate fibrovascular stalks.6 Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells are positive for alpha-1-antitrypsin, neuron-specific enolase, and vimentin. However, inconsistent results have been reported for epithelial and neuroendocrine markers.1 Ultrastructurally, most conspicuous are tumor cells containing large, osmiophilic, zymogen-like granules. Neurosecretory granules have been described in a few tumors. Usually, intermediate cell junctions are rarely observed and microvilli are lacking, but small intercellular spaces are frequent.1

The present case was unusual in that no gross cystic change was identified, and the tumor was predominantly composed of spindle cells. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of the present case included endocrine tumors and spindle cell soft tissue tumors such as benign fibrous histiocytoma and schwannoma, malignant melanoma, and acinar cell carcinoma.

This case is predominantly composed of solid areas showing monomorphic appearance, that resemble endocrine tumors. This type of tumor has not yet been reported. However, endocrine tumors usually lack pseudopapillary formation, as seen in the periphery of this case. Immunohistochemical criteria in favor of solid-pseudopapillary tumors included positivities for alpha-1-antitrypsin and vimentin but negativities for endocrine markers. Moreover, ultrastructural findings in the present case, including zymogen-type granules and acinar spaces with microvilli between tumor cells support the diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary tumor.

This tumor was predominantly composed of spindle cells, thus resembling spindle cell soft tissue tumors. The alternating pattern of Antoni A and B areas, which is a characteristic feature of schwannoma, was not found in this tumor. Furthermore the tumor was negative for S-100, and no long-spacing collagen was present in electron microscopic findings, thus ruling out the possibility of schwannoma.7 Immunohistochemical studies have contributed little to the practical diagnosis of benign fibrous histiocytoma, but ultrastructural findings of this case such as neurosecretory granules and acinar spaces with microvilli between tumor cells supported the diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary tumors.8

These characteristics of spindle cells can also be seen in malignant melanoma. However, no prominent nucleoli were noted in the present case, and immunohistochemical staining for S-100 protein was negative.

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinomas may have a solid pattern, reminiscent of low-grade endocrine tumors. Usually, there are necrotic areas, and prominent nucleoli are characteristic features. These tumors are usually positive for cytokeratin and diffusely positive for chymotrypsin, which are different from the present case.9

CD10 is an endopeptidase responsible for reducing the local concentration of biologic modulators by catabolizing them. It was originally identified in acute leukemia as a "common acute leukoblastic leukemia antigen", but is well known today for its ubiquitous distribution in various tissues. Recently, CD10 was demonstrated in solid-pseudopapillary tumors in a diffuse pattern, therefore, it can be helpful in differential diagnosis in addition to CD56.5

β-catenin immunostaining is useful for differential diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary tumors. The protein β-catenin was originally identified as a submembranous element of the cadherin-mediated cell-to-cell adhesion complex. It has been shown that β-catenin acts as a downstream transcriptional activator of Wnt signaling via accumulation in the nucleus and subsequent complex formation with DNA-binding proteins such as TCF and LEF-1. The association between-genetic alterations of β-catenin and pancreatic tumors had received little attention, however, recent studies revealed nuclear/cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin in solid-pseudopapillary tumors in contrast to membranous reactivity in pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma and neuroendocrine tumor.10

In this case, most of the tumor cells showed nuclear and cytoplasmic positivities for β-catenin and cytoplasmic staining for CD10 and CD56, supporting the diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary tumors.

Because solid-pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas behave as low-grade malignant tumors, an accurate diagnosis is clinically important. This case was unique in that it was small in size, did not show gross cystic change, and was predominantly composed of spindle cells, causing a difficult diagnostic problem.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 3The periphery of the tumor showed focally cystic change and pseudopapillary formations (A and B). |

References

1. Solcia E, Capella C, Kloppel G. Rosai J, Sobin LH, editors. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor. Tumors of the exocrine pancreas. Atlas of tumor pathology. Tumors of the pancreas. 1997. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C.: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;120–128.

2. Klimstra DS, Wenig BM, Heffess CS. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a typically cystic carcinoma of low malignant potential. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000. 17:66–80.

3. Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2005. 200:965–972.

4. Madan AK, Weldon CB, Long WP, Johnson D, Raafat A. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 2004. 85:193–198.

5. Notohara K, Hamazaki S, Tsukayama C, Nakamoto S, Kawabata K, Mizobuchi K, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: immunohistochemical localization of neuroendocrine markers and CD10. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000. 24:1361–1371.

6. Santini D, Poli F, Lega S. Solid-papillary tumors of the pancreas: histopathology. JOP. 2006. 7:131–136.

7. Weiss SW, Goldbrum JR. Strauss M, Gery L, editors. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. Soft tissue tumors. 2001. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby;1146–1160.

8. Weiss SW, Goldbrum JR. Strauss M, Gery L, editors. Benign fibrohistiocytic tumors. Soft tissue tumors. 2001. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby;441–455.

9. Solcia E, Capella C, Kloppel G. Rosai J, Sobin LH, editors. Acinar cell carcinoma. Tumors of the exocrine pancreas. Atlas of tumor pathology. Tumors of the pancreas. 1997. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C.: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;103–112.

10. Tanaka Y, Notohara K, Kato K, Ijiri R, Nishimata S, Miyake T, et al. Usefulness of beta-catenin immunostaining for the differential diagnosis of solidpseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002. 26:818–820.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download