Abstract

Purpose

This study compared the mental symptoms, especially symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), of women who escaped prostitution, helping activists at shelters, and matched control subjects.

Materials and Methods

We assessed 113 female ex-prostitutes who had been living at a shelter, 81 helping activists, and 65 control subjects using self-reporting questionnaires on demographic data, symptoms related to trauma and PTSD, stress-related reactions, and other mental health factors.

Results

Female ex-prostitutes had

significantly higher stress response, somatization, depression, fatigue, frustration, sleep, smoking and alcohol problems, and more frequent and serious PTSD symptoms than the other 2 groups. Helping activists also had significantly higher tension, sleep and smoking problems, and more frequent and serious PTSD symptoms than control subjects.

Conclusion

These findings show that engagement in prostitution may increase the risks of exposure to violence, which may psychologically traumatize not only the prostitutes themselves but also the people who help them, and that the effects of the trauma last for a long time. Future research is needed to develop a method to assess specific factors that may contribute to vicarious trauma of prostitution, and protect field workers of prostitute victims from vicarious trauma.

Prostitution is the practice of engaging in sexual activities with an individual other than a spouse or friend in exchange for payment. Although prostitution is a global and deeply rooted social phenomenon, substantial disparity exists in its perception, depending on different social and cultural factors.1 One view is to consider prostitution as a crime that induces violence; such as human trafficking, sexual abuse, rape, physical or verbal abuse, and racial discrimination, including serious violations of human rights.2,3 The other extreme is to consider prostitution as a type of occupation in which the people involved are known as special workers, or "sex workers".4 Despite the different points of view, a general consensus shows that women engaging in prostitution may be exposed to serious health risks,5-7 such as sexually transmitted diseases and HIV.8-10 In addition, studies on mental health problems suggest that depressive symptoms, anxiety, and psychological distress are higher in women in prostitution.5,11,12

To examine the mental health of women who are engaged in prostitution, the characteristics of the process of prostitution must be understood. According to previous studies, prostitution is essentially a multi-traumatic phenomenon.13 First, women in prostitution may occasionally be involved in violence.3 A recent study of 854 women in prostitution in 9 countries reported that 70 - 95% of the women experience physical assault, among which 60 - 75% had been raped.2 Similarly in Korea, where prostitution is illegal, prostitutes experience sexual and physical violence. In a study of 100 Korean women in prostitution, 96% of respondents answered that they experienced physical danger from weapons, physical violence, and injury from rape.14

Direct or indirect exposure to traumatic events in the course of prostitution is associated with psychological problems, including PTSD.15 PTSD can result from extremely traumatic experiences that are direct, personal, and involve actual or threatened death or serious injury; threat to one's personal integrity, witnessing an event that involves death, injury, or threat to the physical integrity of another person, or learning about unexpected or violent death, serious harm, or threat of death or injury experienced by a family member or close associate.16 Several factors have been associated with an increased risk of developing PTSD following trauma exposure. These include background variables such as childhood trauma, comorbid mental health problems, family instability, and substance abuse.17,18

PTSD is a chronically disabling disorder associated with a large degree of morbidity. It rarely exists as a pure disorder and psychiatric comorbidities such as depression, alcohol abuse, substance abuse, other anxiety disorders, and suicidal tendencies worsen the burden of this disorder.19 PTSD may be especially severe or long lasting when the stressor is planned and implemented by humans such as war, rape, incest, battery, or prostitution rather than natural catastrophes.3

Previous studies on prostitution have shown that prostitutes have a high prevalence of PTSD. Sixty-eight percent of 827 prostitutes in 9 countries met the criteria for lifetime diagnosis of PTSD.3 The severity of PTSD symptoms in the participants in the above study was in the same range as treatment-seeking combat veterans,20,21 battered women in protective shelters,22,23 rape survivors,24 and refugees.25 A study performed in Korea found that 81% of women with a history of prostitution had symptoms of PTSD,14 and research has suggested that prostitutes might have many risk factors for developing PTSD. Experiences of child sexual abuse are commonly reported among prostitutes. Additionally, violence related to prostitution and adult sexual assaults are prevalent.5,26

Exposure to violence through engagement in prostitution may contribute to persistent and severe psychological problems in not only direct victims but also people in close proximity who can suffer from a range of emotional symptoms in spite of not being directly exposed to the traumatic events. This phenomenon has been described by a number of terms, including indirect traumatization, and has been documented among children of Holocaust survivors,27 wives of combat soldiers,28 and therapists who treat trauma victims.29 A number of terms describe the negative impacts that result from working with traumatized victims, including "burnout", "compassion fatigue", "secondary traumatic stress", and more recently "vicarious traumatization".30

The term "vicarious trauma" was first used by McCann and Pearlman to describe pervasive changes occurring within clinicians or counselors over time from working with victims who experienced sexual trauma.31 In our study, the term was used to describe secondary trauma and/or traumatic stress. The unique features of counseling for sexual violence that contribute to the development of vicarious traumatization result from empathically listening to victims as they share graphic details of their traumatic experiences and psychological pain. Compared to other fields, sexual violence counselors have a higher risk of experiencing vicarious trauma.31,32 In a qualitative study of female counselors working with sexual assault victims, approximately 2/3 of participants reported intrusive imagery, dreams, and thoughts, including increased vigilance related to their safety, which decreases the level of trust in social interactions.33 Counselors and researchers who experience these negative effects may stop working with traumatized individuals,34 and the activists helping women exposed to trauma may experience more vicarious traumatic effects than workers in other fields. Therefore, recognizing and resolving vicarious traumatization may be crucial to the well-being of victims as well as counselors.35

Only a few studies examined PTSD symptoms or its associations in the mental health of prostitutes and control groups. In particular, a controlled comparison of vicarious traumatic effects among field workers who help female prostitutes has not yet been performed.

The present study compared the mental health status of former female prostitutes who live in shelters, field workers helping prostitutes in shelters, and a normal control group. In keeping with the literature, we examined the specific PTSD symptoms and other manifestations of distress and mental health among the 3 groups.

We collected cross-sectional data using selfreporting questionnaires for 2 mos. Participants were former female prostitutes in shelters (exprostitutes), activists helping the ex-prostitutes in shelters (activists), and a control group. Exprostitutes and activists were recruited from 18 shelters with the support of the Bombit Women's Foundation that aids female prostitutes and workers who help prostitutes in Korea.

Female subjects age-matched to the ex-prostitutes were recruited from the surrounding community of each shelter as the control group. Data were collected from all 3 groups during the same period, and the subjects were notified orally and also in writing on the first page of the questionnaire that their answers would be used only for research purposes. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The questionnaire consisted of demographic data, symptoms related to trauma and PTSD, stress-related reactions, and other mental health factors. Participants' PTSD symptoms were assessed using the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS)36 and the modified Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R).37 DTS is a self-rating scale that assesses the frequency and severity of 17 symptoms related to PTSD on a scale from 0 to 4. IES-R includes 22 items scored on a 5-point scale that is designed to determine the impact of traumatic events. Scale validation studies conducted in Korea have shown that the measures are all high in reliability and validity.38,39 Stress reactions were assessed using the Stress Response Inventory (SRI),40 a 39-item self-rating instrument developed to assess the severity of stress responses, specifically on emotional, somatic, cognitive, and behavioral responses that occurred in the previous week. Stress reactions were rated on a Likert scale ranging from "not at all" (0), to "absolutely" (4). The rated items were factor-analyzed using 7 subscales: tension, aggression, somatization, anger, depression, fatigue, and frustration.

Other factors related to mental health were included in the questionnaires, such as sleep, personal past history, family history varying from psychiatric illness to physical illness, and smoking or alcohol drinking history. Questions on sleep involved the frequency of awakening, whether alcohol or drugs were used for the induction of sleep, quality of sleep, early morning awakening, and the restoration level of sleep.

The statistical significance of differences among the results of the demographic data of the 3 groups was assessed by chi-square test and one-way ANOVA analysis. One-way ANOVA was also performed to analyze the differences in the total score, subscale score of the DTS, IES-R and SRI, and the sleep-, drinking-, and smoking-related scores of the 3 groups. Duncan's multiple comparisons were then applied as post-hoc analysis to determine where the differences existed among the 3 groups. Pearson's correlation analysis was applied to determine which variables correlated significantly with symptoms of PTSD and mental health problems. The significance level was determined as p < 0.05.

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. A total of 113 ex-prostitutes (mean age, 25.58 ± 3.22 yr), 81 activists (mean age, 34.78 ± 8.00 yr), and 65 control subjects (mean age, 24.81 ± 5.22 yr) participated. The ages of the ex-prostitute group and the control group were not significantly different. None theless, there was a significant age difference between the activists and the other 2 groups (p < 0.001). In addition, there were significant differences in marital status, education level, and financial status among the 3 groups. Specifically, educational level and economic level were higher in the activists and the control group than in the ex-prostitute group.

The duration of prostitution of the ex-prostitutes was 5.8 yr on average and the initial age when they first engaged in prostitution ranged from 14 to 39 yr. The longer duration the women engaged in prostitution, the more diverse types of prostitution were reported. The primary type of prostitution was bar- associated (50%; N = 57) followed by "ticket coffee shops" (selling tea with sexual activities), business of prostitution by employing women to visit customers for sex (38%; N = 43), brothels (18%; N = 21), massage parlors, and "Wonjo Kyojae" in Korean (The meaning is a date helping each other. It usually happens between people not close in age, with a middle-aged man giving money to a young girl for sexual intercourse). The mean duration of residence in shelters for those who participated in the questionnaire was 8.7 mos.

There was a significant difference in the frequency and severity of PTSD symptoms among the ex-prostitutes, activists, and control group. Exprostitutes showed more of the PTSD symptoms than the activists. The activists also showed higher scores than the control group (DTS frequency, F= 22.97, p < 0.001; DTS severity, F = 24.54, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Specifically, the subscales of the 3 cardinal symptoms (re-experience, avoidance, and hyperarousal) were significantly greater amongst the ex-prostitutes than the other 2 groups. Between the 2 groups, the activists group showed greater scores in DTS than the control group. The mean scores of the IES-R among the ex-prostitutes and activists were significantly greater than the control group, but there were no statistically significant differences between the ex-prostitutes and activists.

As shown in Table 3, the 3 groups significantly differ in SRI scores. Activists showed greater scores in somatization, fatigue, depression, and frustration than the other 2 groups. Compared to the control group, the activists group also had a higher mean total score of SRI and, particularly in the scales of depression and tension. Ex-prostitutes scored higher on tension than the control group, but were not significantly different from those of the activists.

Similarly, the total mean scores of the scales related to sleep were significantly different among the 3 groups. The total mean scores of drinkingand smoking-related scales also showed significant differences. In comparison with the activists group and the control group, sleep troubles and smoking problems were noticeable in the ex-prostitute group whereas the activists exhibited more sleep and smoking problems than the control group. The ex-prostitutes group had the most drinking problems compared to the activists and the control group.

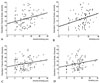

The duration of prostitution (r = 0.22, p = 0.047) and age (r = 0.21, p = 0.05) of subjects showed significant positive correlations to the severity of PTSD symptoms, measured by DTS (Fig. 1). The severity of PTSD symptoms measured by DTS was also significantly positively correlated to smoking (r = 0.32, p = 0.002) and drinking problems (r = 0.27, p = 0.01). Similarly, the frequency of PTSD symptoms had significantly positive correlations to smoking (r = 0.20, p = 0.047) and drinking problems (r = 0.22, p = 0.032; Fig. 2). Sleep troubles had a positive correlation with the frequency (r = 0.45, p < 0.001) along with the severity of the PTSD symptoms, measured by DTS (r = 0.52, p < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Age was significantly correlated with smoking problems (r = 0.30, p = 0.002) whereas duration of prostitution showed significantly positive correlations with smoking (r = 0.45, p < 0.001) and drinking problems (r = 0.30, p = 0.003). Sleep troubles were positively correlated to smoking (r = 0.25, p = 0.011) and drinking problems (r = 0.26, p = 0.007). Sleep troubles were also positively correlated to the total mean scores of SRI (r = 0.60, p < 0.001), and to the subscale scores of SRI, such as tension (r = 0.55, p < 0.001), aggression (r = 0.57, p < 0.001), somatization (r = 0.50, p < 0.001), anger (r = 0.51, p < 0.001), depression (r = 0.58, p < 0.001), fatigue (r = 0.52, p < 0.001), and frustration (r = 0.53, p < 0.001). IES-R scores also showed a significantly positive correlation to sleep problems (r = 0.50, p < 0.001).

The duration of residence in shelters was negatively correlated to the frequency (r = - 0.33, p = 0.003) and severity of PTSD symptoms (r = - 0.38, p = 0.001) whereas it was inversely correlated to IES-R (r = - 0.27, p = 0.014) and SRI (r = - 0.21, p = 0.049) with subscales of SRI, including tension (r = - 0.26, p = 0.012), somatization (r = - 0.21, p = 0.05), and frustration (r = - 0.22, p = 0.039), along with problems with smoking (r = - 0.27, p = 0.01) and drinking (r = - 0.26, p = 0.014).

We investigated PTSD symptoms of ex-prostitutes, activists helping prostitutes, and control subjects in the community. We also examined the association between PTSD symptoms and other mental health problems, such as stress reactions, sleep, smoking and alcohol problems. There are 3 implications in this research. This is the first study dealing with PTSD symptoms of not only the women engaged in prostitution, but also the vicarious traumatic effects and mental health of field workers helping the prostitutes. Second, contrary to previous studies conducted on prostitutes, this study focused on ex-prostitutes who had escaped prostitution and were rehabilitating in shelters. Third, while previous studies on female prostitutes were single-group studies, this study was a controlled and compared study among 3 female groups.

We found that field workers helping prostitutes experienced PTSD symptoms more frequently and more severely than control group. These workers also reported higher rates of tension, sleep troubles, and smoking problems than the control group. These findings support our hypothesis that traumatic experience related to prostitution would have influence on mental health, such as PTSD, not only among the ex-prostitutes but also among the activists traumatized indirectly.

To out best knowledge, there has been no previous controlled study that examined the level of vicarious trauma among field workers helping prostitutes. The present findings are consistent with previous non-controlled studies on vicarious trauma. Vicarious traumatization in sex violence counselors showed a pattern similar to that of previous studies despite its insignificant influence. Specifically, the influences include intrusion of traumatic images,32,33,41,42 avoidance,41 depression and frustration with an increase of drug use,42 disordered sleep, reduction of energy,33,43 damage to self-confidence and values32 with a change in cognitive schema.43 According to previous findings, variables that moderate the development of vicarious trauma include personal characteristics, such as gender,41 age44 and counselors' own trauma or abuse history.45,46 However, in regard to counselors' own trauma, Schauben and Franzier29 did not find that past trauma history significantly interacted with caseload characteristics in producing symptoms in counselors. It was also reported that there was no notable difference in vicarious trauma symptoms between those with and without personal abuse history.47 We found that vicarious trauma symptoms correlated significantly with the amount of exposure to trauma and the work characteristics such as the percentage of sexual violence cases within the caseload29 and the number of working hours spent with traumatized victims.41,48-50 Therefore, generalization of the results is difficult, and it may be necessary to consider individual characteristics of counselors whereas other variables that may be associated with the development of vicarious trauma are negative coping strategies, level of personal stress, and training for new and experienced counselors.51

Although Roman et al.4 reported that there was no difference in mental health between sexworkers and control groups, numerous studies have suggested that sex-workers experience diverse psychological symptoms; such as anxiety, depression, and personality disorders.5,11,12 Similar results also found that women who engage in prostitution experience PTSD symptoms as a psychological consequence of violence associated with prostitution.10,13,52,53 Compared to other groups, prostitute victims in the present study reported severe and frequent rates of PTSD and other distress symptoms, such as tension, aggression, somatization, anger, depression, fatigue, and frustration. Although ex-prostitutes who participated in this study had not engaged in prostitution for an average of 8.7 mos, they still experienced serious PTSD and other distress symptoms. The results were consistent with a Canadian study that compared women who were still in prostitution to those who were not. The study suggests that ex-prostitute respondents are only slightly less likely to experience depression but are more likely to experience anxiety attacks and emotional trauma than their counterparts who continually engage in prostitution.54

Recently, an Australian study showed that female street-based sex workers who reported current PTSD symptoms had experienced a significantly larger number of trauma than sex workers who did not report current PTSD symptoms.55 In addition, the current study found that the reported PTSD symptoms increased proportionally to the length of the years that women engaged in prostitution. Multiple traumas related to engagement in prostitution for a long time are associated with the risk of developing PTSD and severity of symptoms. These results were consistent with previous research showing that the longer the exposure period to trauma, the more severe and persistent the PTSD symptoms.15,56 Therefore, we believe that ex-prostitutes who engaged in prostitution for a long time are in need of great help and support.

In our study, smoking and drinking problems among women who engaged in prostitution were serious compared to the control group and the measures were positively correlated to the severity and frequency of PTSD symptoms. Previous studies showed that the risk of developing drinking problems is higher among women with PTSD caused by sexual violence,57 while drug abuse problems are higher among prostitutes.11,58 The theory that alcohol and cigarettes play a role in self-medication to reduce psychological pain is widely known,59 and 1 study reported that women use drugs to obtain a numbing effect during prostitution. Substance abuse enables PTSD patients to attain cognitive avoidance, while treating the concomitant substance abuse is difficult in cases with residual PTSD symptoms, due to their continuous avoidance.54,60 Therefore, problems pertinent to substance abuse should be handled at the same time as the PTSD of female prostitutes.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, demographic data such as age, marital status, education, and social and economic status showed significant differences between exprostitutes, field workers, and controls. Younger age, lower socioeconomic status, and lack of education are associated with the development of PTSD, but neither increase the risk by more than 50%.61,62 Therefore, the findings might have been influenced by demographic factors. Second, the questionnaires were all self-reports with no psychiatric diagnosis by an outside expert. Third, field workers' vicarious trauma symptoms were assessed using a modified version of a questionnaire that was developed to assess the direct victims of PTSD. Fourth, past trauma history such as child sexual abuse, rape, and family instability, which are considered risks of developing PTSD, were unfortunately not examined in this study. Since variables related to vicarious trauma were not examined in the field worker group, it is difficult to determine whether the trauma symptoms of field workers were caused indirectly by working with ex-prostitutes or directly by the field workers' own risk factors for PTSD.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study contributes to our knowledge of the populations that are directly and indirectly traumatized by after escaping from prostitution, women show diverse psychological symptoms related to PTSD and distress; furthermore, the field workers helping prostitutes also report considerable vicarious traumatic symptoms. These findings show that engagement in prostitution may increase the risks of exposure to violence that may act as psychological trauma not only to the victims themselves but also to the people who help them, indicating that the influence of the trauma lasts for a long time. PTSD is a chronic condition that can be a social and economic burden to the victims, people around them, and society. Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment are extremely important.63

These findings raise several issues. In Korea, the act on the prevention of the sex trade and protection of its victims in 2004 criminalized human trafficking and stiffened penalties for brothel owners. A number of shelters, self-support centers, and legal, medical, and vocational assistance including secure housing and paying off debts have been provided. However, mental health support is relatively insufficient. The results of the present study suggest that psychiatric intervention for women engaged in prostitution are required and outreach services such as counseling centers and crisis hotlines are necessary to prevent mental health problems. Future research is needed to develop an assessment method for vicarious trauma of prostitution and specific factors that may contribute to vicarious trauma or protect field workers from vicarious trauma need to be evaluated. In this regard, longitudinal studies may be useful in understanding the processes involved in vicarious trauma and the temporal relationship between coping strategies and the traumatic effects of contact with victims.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Correlation between severity subscale of Davidson Trauma Scale, duration of engagement in the sex trade, and age in ex-prostitutes. Pearson correlation coefficient. *p = 0.047; †p = 0.05. |

| Fig. 2Correlation between severity subscale of Davidson Trauma Scale and smoking and alcohol drinking degree in ex-prostitutes. Pearson correlation coefficient. *p = 0.01; †p = 0.002; ‡p = 0.032; §p = 0.047. |

| Fig. 3Correlation between severity subscale of Davidson Trauma Scale and degree of sleep problems in ex-prostitutes. Pearson correlation coefficient. *p < 0.001; †p < 0.001. |

References

1. Kramer LA. Emotional experiences of performing prostitution: prostitution, trafficking, and traumatic stress. 2003. Binghamton: Haworth Press.

2. Barry K. The prostitution of sexuality. 1996. New York: New York University Press.

3. Farley M, Cotton A, Lynne J, Zumbeck S, Spiwak F, Reyes ME, et al. Prostitution and trafficking in nine countries: an update on violence and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Pract. 2003. 2:33–74.

4. Romans SE, Potter K, Martin J, Herbison P. The mental and physical health of female sex workers: a comparative study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001. 35:75–80.

5. Brody S, Potterat JJ, Muth SQ, Woodhouse DE. Psychiatric and characterological factors relevant to excess mortality in a long-term cohort of prostitute women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005. 31:97–112.

6. Potterat JJ, Brewer DD, Muth SQ, Rothenberg RB, Woodhouse DE, Muth JB, et al. Mortality in a longterm open cohort of prostitute women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004. 159:778–785.

7. Vanwesenbeeck I. Another decade of social scientific work on sex work: a review of research 1990-2000. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2001. 12:242–289.

8. Chen XS, Yin YP, Liang GJ, Gong XD, Li HS, Poumerol G, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Yunnan, China. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005. 19:853–860.

9. Gossop M, Powis B, Griffiths P, Strang J. Female prostitutes in south London: use of heroin, cocaine and alcohol, and their relationship to health risk behaviours. AIDS Care. 1995. 7:253–260.

10. Nguyen AT, Nguyen TH, Pham KC, Le TG, Bui DT, Hoang TL, et al. Intravenous drug use among street-based sex workers: a high-risk behavior for HIV transmission. Sex Transm Dis. 2004. 31:15–19.

11. Alegría M, Vera M, Freeman DH Jr, Robles R, Santos MC, Rivera CL. HIV Infection, risk behaviors, and depressive symptoms among Puerto Rican sex workers. Am J Public Health. 1994. 84:2000–2002.

12. El-Bassel N, Schilling RF, Gilbert L, Faruque S, Irwin KL, Edlin BR. Sex trading and psychological distress in a street-based sample of low-income urban men. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000. 32:259–267.

13. Farley M, Barkan H. Prostitution, violence, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Women Health. 1998. 27:37–49.

14. Kim HS. Violent characteristics of prostitution and posttraumatic stress disorder of women in prostitution [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. 2002. Seoul: Sung-Gong-Hoe University.

15. Kaysen D, Resick PA, Wise D. Living in danger: the impact of chronic traumatization and the traumatic context on posttraumatic stress disorder. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2003. 4:247–264.

16. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Text Rev. 2000. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

17. Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Yehuda R, Charney DS. Childhood physical abuse and combatrelated posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 1993. 150:235–239.

18. McKenzie N, Marks I, Liness S. Family and past history of mental illness as predisposing factors in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2001. 70:163–165.

19. Brunello N, Davidson JR, Deahl M, Kessler RC, Mendlewicz J, Racagni G, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder: diagnosis and epidemiology, comorbidity and social consequences, biology and treatment. Neuropsychobiology. 2001. 43:150–162.

20. Schlenger WE, Kulka RA, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, et al. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in the Vietnam generation: A multimethod, multisource assessment of psychiatric disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1992. 5:333–363.

21. In : Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM, editors. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. 1993. Paper presented at the 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, Texas:

22. Houskamp B. Assessing and treating battered women: a clinical review of issues and approaches. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 1994. 64:79–89.

23. Kemp A, Rawlings EI, Green BL. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in battered women: a shelter sample. J Trauma Stress. 1991. 4:137–148.

24. Bownes IT, O'Gorman EC, Sayers A. Assault characteristics and posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991. 83:27–30.

25. Ramsay R, Gorst-Unsworth C, Turner S. Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of organised state violence including torture. A respective series. Br J Psychiatry. 1993. 162:55–59.

26. Tyler KA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB, Cauce AM. The effects of a high-risk environment on the sexual victimization of homeless and runaway youth. Violence Vict. 2001. 16:441–455.

27. Sorscher N, Cohen LJ. Trauma in children of Holocaust survivors: transgenerational effects. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1997. 67:493–500.

28. Beckham JC, Lytle BL, Feldman ME. Caregiver burden in partners of Vietnam War veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996. 64:1068–1072.

29. Schauben LJ, Frazier PA. Vicarious trauma: the effects on female counselors of working with sexual violence survivors. Psychol Women Q. 1995. 19:49–64.

30. Sabin-Farrell R, Turpin G. Vicarious traumatization: implications for the mental health of health workers? Clin Psychol Rev. 2003. 23:449–480.

31. McCann L, Pearlman LA. Vicarious traumatization: a framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. J Trauma Stress. 1990. 3:131–149.

32. Pearlman LA, MacIan PS. Vicarious traumatization: an empirical study of the effects of trauma work on trauma therapists. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1995. 26:558–565.

33. Steed LG, Downing R. A phenomenological study of vicarious traumatisation amongst psychologists and professional counsellors working in the field of sexual abuse/assault. retrieved 2006 Nov 11. 1998-2:Australas J Disaster Trauma Studies [serial online];Available from: URL:

http://www.massey.ac.nz/%7Etrauma/issues/1998-2/steed.htm.

34. Figley CR. Stamm BH, editor. Compassion fatigue: toward a new understanding of the cost of caring. Secondary traumatic stress: Self care issues for clinicians, researchers and educators. 1999. 2nd ed. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press;3–28.

35. Pearlman LA, Saakvitne KW. Trauma and the therapist: countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. 1995. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

36. Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 1997. 27:153–160.

37. Weiss DS, Marmar CR. Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. The impact of event scalerevised. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. 2004. New York, NY: Guilford Press;168–189.

38. In : Lim HK, Woo JM, Kim TS, Kim TH, Yang JC, Choi KS, editors. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R-K). 2006. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the Korean Neuropsychiatric Association; Seoul, Korea.

39. Seo HJ, Jung SG, Lim HK, Chee IS, Lee KU, Paik KC, et al. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Davidson Trauma Scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2008. 49:313–318.

40. Koh KB, Park JK, Kim CH, Cho S. Development of the stress response inventory and its application in clinical practice. Psychosom Med. 2001. 63:668–678.

41. Kassam-Adams N. Stamm BH, editor. The risks of treating sexual trauma: stress and secondary trauma in psychotherapists. Secondary traumatic stress: Self care issues for clinicians, researchers, and educators. 1999. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press;37–48.

42. Rich KD. Edmunds SB, editor. Vicarious traumatization: A preliminary study. Impact: Working with sexual abusers. 1999. Brandon, VT: Safer Society Press;75–88.

43. Iliffe G, Steed LG. Exploring the counselor's experience of working with perpetrators and survivors of domestic violence. J Interpers Violence. 2000. 15:393–412.

44. Ghahramanlou M, Brodbeck C. Predictors of secondary trauma in sexual assault trauma counselors. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2000. 2:229–240.

45. Jenkins SR, Baird S. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma: a validational study. J Trauma Stress. 2002. 15:423–432.

46. In : Pearlman LA, MacIan PS, Johnson G, Mas K, editors. Understanding cognitive schemas across groups: empirical findings and their implications. 1992. Paper presented at the 8th annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; Los Angeles.

47. Benatar M. A qualitative study of the effect of a history of childhood sexual abuse on therapists who treat survivors of sexual abuse. J Trauma Dissociation. 2000. 1:9–28.

48. Brady JL, Guy JD, Poelstra PL, Brokaw BF. Vicarious traumatization, spirituality, and the treatment of sexual abuse survivors: a national survey of women psychotherapists. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1999. 30:386–393.

49. Chrestman KR. Stamm BH, editor. Secondary exposure to trauma and self reported distress among therapists. Secondary traumatic stress: Self care issues for clinicians, researchers and educators. 1999. 2nd ed. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press;29–36.

50. Steed L, Bicknell J. Trauma and the therapist: the experience of therapists working with the perpetrators of sexual abuse. . retrieved 2006 Nov 11. 2001-1:Australas J Disaster Trauma Studies [serial online];Available from: URL:

http://www.massey.ac.nz/~trauma/issues/2001-1/steed.htm.

51. Follette VM, Polusny MM, Milbeck K. Mental health and law enforcement professionals: trauma history, psychological symptoms, and impact of providing services to child sexual abuse survivors. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1994. 25:275–282.

52. Chudakov B, Ilan K, Belmaker RH, Cwikel J. The motivation and mental health of sex workers. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002. 28:305–315.

53. Valera RJ, Sawyer RG, Schiraldi GR. Perceived health needs of inner-city street prostitutes: a preliminary study. Am J Health Behav. 2001. 25:50–59.

54. Benoit C, Millar A. Dispelling myths and understanding realities: working conditions, health status and exiting experiences of sex workers. Retrieved 2006 Nov 11. Available from: URL: http://web.uvic.ca/~cbenoit/papers/DispMyths.pdf.

55. Roxburgh A, Degenhardt L, Copeland J. Posttraumatic stress disorder among female street-based sex workers in the greater Sydney area, Australia. BMC Psychiatry. 2006. 6:24.

56. Buydens-Branchey L, Noumair D, Branchey M. Duration and intensity of combat exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990. 178:582–587.

57. Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L. Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997. 54:81–87.

58. Gilchrist G, Gruer L, Atkinson J. Comparison of drug use and psychiatric morbidity between prostitute and non-prostitute female drug users in Glasgow, Scotland. Addict Behav. 2005. 30:1019–1023.

59. Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997. 4:231–244.

60. Read JP, Brown PJ, Kahler CW. Substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders: symptom interplay and effects on outcome. Addict Behav. 2004. 29:1665–1672.

61. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in traumaexposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000. 68:748–766.

62. Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003. 129:52–73.

63. Davidson JR. Long-term treatment and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004. 65:Suppl 1. 44–48.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download