Abstract

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE) is a rare tumor of vascular origin. While it can be found in any tissue, it is most often found in lung and liver and usually has an intermediate behavior. EHEs originating from pleural tissue have been less frequently described than those from other sites. Furthermore, to date, all of the cited pleural EHEs were described as highly aggressive. In the present report, we describe a rare case of pleural EHE extending to lung and bone in a 31-year-old woman. The histological diagnosis was confirmed by both conventional examination and immunohistochemistry. Her disease stabilized during the 4th course of adriamycin (45 mg/m2, day 1-3), dacarbazine (300 mg/m2, day 1-3) and ifosfamide (2,500 mg/m2, day 1-3) with mesna, and she survived for 10 months after the diagnosis.

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE) is a rare tumor of vascular origin. Pulmonary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (PEH) was first described in 1975 by Dail and Leibow and was originally termed "intravascular bronchioloalveolar tumor (IVBAT)".1 Dail confirmed the vascular nature of the tumor and thus, in recent literature, the term PEH has been used in lieu of IVBAT. PEH has subsequently been recognized as the pulmonary counterpart of EHE occurring in other sites. EHE typically arises in variable locations such as the lung, liver, bone, soft tissue, skin, gastrointestinal tract, brain, mediastinum, spleen, breast, testis, thyroid, and heart.1 The tumor has a clinical course intermediate between benign hemangioma and angiosarcoma.1 Its etiology is still unknown.

EHEs originating from pleura have been less frequently described than those from other sites. The pleural EHE is more aggressive than others.2 Here we describe an uncommon case of pleural EHE extending to the lungs and bone in a 31-year-old woman. To our knowledge, this is the first case of an EHE originating from pleura in Korea.

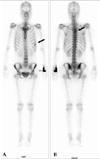

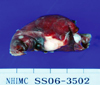

A 31-year old woman was admitted to the hospital for upper back and radiating, bilateral shoulder pain of 5 months duration. She was a non-smoker and had no history of asbestos exposure. She complained of dull pain around the 5th vertebral body that was exacerbated in the upright position and relieved when supine. Physical examination and laboratory findings were unremarkable. A chest computerized tomography (CT) showed a nodular pleural thickening on the right side of the chest including a 1.5 cm-sized extrapleural tumorous lesion on the apicoposterior segment, several foci of subpleural nodular lesions on the right middle and lower lobes, and bone metastases affecting the 5th and 12th thoracic vertebral bodies (Fig. 1A). A bone scan showed a focally increased uptake at the level of the 5th thoracic spine, suggesting bone metastasis, and a linear uptake at the 7th left anterior rib that could not be ruled out as a possible bone metastasis (Fig. 2). A thoracoscopic wedge resection of the right lower lobe of the lung was performed. Grossly, the specimen consisted of a wedge of resected lung tissue measuring 5.0 × 3.0 × 2.5 cm with multiple scattered and variably sized subpleural whitish-tan plaques, at the largest diameter measuring 1.2 × 1.0 × 0.2 cm (Fig. 3). Histologically, the tumor showed pleura-based intraparenchymal growth (Fig. 4A). Microscopically, a hyalinized stroma surrounded the tumor cells. The epithelioid cells contained slightly pleiomorphic, rounded nuclei and scanty cytoplasm with prominent intracytoplasmic vacuoles. Few mitotic figures were observed. Hemorrhagic necrosis was evident and surgical margins were clear (Fig. 4B). Immunohistologically, the tumor cells were negative for cytokeratin, calretinin, desmin, and S-100 protein (Fig. 5A). However, the tumor cells showed diffuse strong positivity for α-SMA and vimentin, diffuse weak positivity for factor VIII and CD31 and focally weak positivity for CD34 (Fig. 5B). As a result of examination and laboratory findings, the patient was diagnosed with pleural epithelioid hemangioendothelioma with peripheral lung parenchymal invasion and multiple bone metastases to the spine. Palliative radiotherapy on the spine and chemotherapy with adriamycin (45 mg/m2, day 1, every 3 weeks) were started as soon as the diagnosis was confirmed. When the progression of the disease was confirmed on the chest CT after the 3rd round of adriamycin chemotherapy (Fig. 1B), the regimen was switched to Mesna-Doxorubicin-Ifosfamide-Dacarbazine (MAID) to be administered every 4 weeks as an injection of adriamycin (45 mg/m2, day 1 - 3), dacarbazine (300 mg/m2, day 1 - 3) and ifosfamide (2,500 mg/m2, day 1 - 3) with mesna. After the 2nd course of the MAID regimen, the chest CT showed stable disease, and patient's symptoms improved (Fig. 1C). She continued to receive MAID chemotherapy and survived for 10 months after her diagnosis.

The pleura is one of many anatomical sites of origin for EHE. EHE originating from the pleura is an extremely rare. To date, only 13 cases of pleural EHE have been reported in the English literature (Table 1).2-6

In many respects, pleural EHE differs from its pulmonary counterpart (PEH). According to the literature, pleural EHE affects symptomatic, older adult males, while PEH usually affects asymptomatic, young to middle-aged females.2-9 All reported cases of diffuse pleural EHE were highly malignant and widely metastatic regardless of the fact that they took the form of an EHE tumor.2,3 Whereas PEH usually progresses slowly with intermediate behavior, pleural EHE has an aggressive clinical course and a poor prognosis.2-8

The poor prognostic factors of PEH include the presence of respiratory symptoms or pleural effusion on chest radiography at presentation, extensive intravascular, endobronchial, or interstitial tumor spread, hepatic metastases, peripheral lymphadenopathy and the presence of spindle cells in the tumor.9 Variable chemotherapeutic agents and radiotherapy regimens have been used in affected patients but showed no demonstrable therapeutic benefit. As the treatment of choice for PEH, a surgical excision of the nodules seems to be appropriate, although in asymptomatic patients no therapy can be considered.8 However, in pleural EHE, a complete surgical resection is usually impossible. An effective treatment has not yet been established, although Pinet et al. reported a case of an aggressive form of pleural EHE with complete remission after treatment with carboplatine plus etoposide.4

Differentiation of pleural EHE from PEH is important because prognosis and treatment depend on the tumor's location. A differential diagnosis can be made by a gross or radiologic examination on the presence or absence of a discrete nodular mass formation in subpleural lung parenchyma and a histological examination on an intravascular, intraalveolar, and intrabronchial growth pattern.7

In addition, the differential diagnosis of pleural EHE from a diffuse pleural carcinomatosis or mesothelioma should be given careful consideration due to their similar radiologic appearance. The diagnosis of EHE is suspected based on histological features and confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Positive staining with an anti-vimentin antibody and anti-factor VIII, BNH9, or anti-CD 31 antibodies confirms the diagnosis.10 Anti-factor VIII and BNH 9 stain can highly distinguish endothelial cells from others. The negativity of anti-cytokeratin staining excludes tumors of an epithelial origin. This is imperative for pleural primitive tumors in order to exclude mesothelioma or carcinoma.10

In this report we describe a patient who was diagnosed with pleural EHE confirmed by immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of a unilateral pleural effusion. The patient sustained stable disease long-term and her symptoms improved after systemic chemotherapy with adriamycin, dacarbazine, and ifosfamide with mesna.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1On chest CT scan, the largest diameter of the extrapleural tumorous lesion on the apicoposterior segment is (A) 15 mm at initial diagnosis, (B) 30.7 mm after the 3rd adriamycin (45 mg/m2, day 1, every 3 wks), and (C) 30.8 mm after the 2nd MAID regimen, administered every 4 wks as an injection of adriamycin (45 mg/m2, day 1 - 3), dacarbazine (300 mg/m2, day 1 - 3) and ifosfamide (2,500 mg/m2, day 1 - 3) with mesna. |

| Fig. 2A bone scan at diagnosis shows a focally increased uptake (A) at the level of the 5th thoracic spine suggesting bone metastasis and (B) a linear uptake at the 7th left anterior rib that could not be ruled out as a potential metastasis. |

| Fig. 3Photograph of a specimen of thoracoscopic wedge resection of the right lower lobe shows multiple scattered and variably sized subpleural whitish-tan plaques. |

| Fig. 4Histological photographs of a lung specimen show (A) pleura-based intraparenchymal tumor growth (H & E ×40) and (B) tumor cells surrounded by a hyalinized stroma with intracytoplasimic vacuolization (H & E ×400). |

References

1. Dail DH, Liebow AA, Gmelich JT, Friedman PJ, Miyai K, Myer W, et al. Intravascular, bronchiolar, and alveolar tumor of the lung (IVBAT). An analysis of twenty cases of a peculiar sclerosing endothelial tumor. Cancer. 1983. 51:452–464.

2. Lin BT, Colby T, Gown AM, Hammar SP, Mertens RB, Chung A, et al. Malignant vascular tumors of the serous membranes mimicking mesothelioma. A report of 14 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996. 20:1431–1439.

3. Yousem SA, Hochholzer L. Unusual thoracic manifestations of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987. 111:459–463.

4. Pinet C, Magnan A, Garbe L, Payan MJ, Vervloet D. Aggressive form of pleural epithelioid haemangioendothelioma: complete response after chemotherapy. Eur Respir J. 1999. 14:237–238.

5. Crotty EJ, McAdams HP, Erasmus JJ, Sporn TA, Roggli VL. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the pleura: clinical and radiologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000. 175:1545–1549.

6. Al-Shraim M, Mahboub B, Neligan PC, Chamberlain D, Ghazarian D. Primary pleural epithelioid haemangioendothelioma with metastases to the skin. A case report and literature review. J Clin Pathol. 2005. 58:107–109.

7. Zhang PJ, Livolsi VA, Brooks JJ. Malignant epithelioid vascular tumors of the pleura: report of a series and literature review. Hum Pathol. 2000. 31:29–34.

8. Kitaichi M, Nagai S, Nishimura K, Itoh H, Asamoto H, Izumi T, et al. Pulmonary epithelioid haemangioendothelioma in 21 patients, including three with partial spontaneous regression. Eur Respir J. 1998. 12:89–96.

9. Weiss SW, Ishak KG, Dail DH, Sweet DE, Enzinger FM. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and related lesions. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1986. 3:259–287.

10. Miettinen M, Lindemayer AE, Chaubal A. Endothelial cells markers CD31, C34 and BNH9 antibody to H and Y-antigens. Evaluation of their specificity and sensitivity in the diagnosis of vascular tumors and comparison with Von Willebrand factor. Mod Pathol. 1994. 14:141–149.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download