Abstract

Chronic pneumonitis of infancy (CPI) is a very rare interstitial lung disease. Its pathological features differ from other types of interstitial pneumonia that occur in adults and children. The mortality rate of CPI is high, even with treatment. We report a case of a 3 month old girl diagnosed with CPI after an open lung biopsy who improved after proper treatment.

Chronic pneumonitis of infancy (CPI) was first described by Katzenstein et al. in 1995.1

CPI is a very rare form of interstitial lung disease occurring in otherwise healthy infants and very young children.1,2 The true incidence of CPI is unknown. Its pathological features differ from other types of interstitial pneumonia that occur in adults and children,1,3 and the mortality rate of CPI is high, even with treatment.1,2 Among the few previously reported cases of CPI, we could not find any which showed clinical improvement after treatment.1-5 In this report, we present the case of a 3 month old girl diagnosed with CPI following open lung biopsy who improved after proper treatment.

The patient, a 3-month-old girl born by normal delivery at term, had been healthy up until the onset of symptoms immediately prior to admission. She was admitted to the pediatric department of Severance hospital after a 10 day history of loose cough, rhinorrhea, and deterioration of her general health with progressive dyspnea and tachypnea. The family had no specific history of lung disease.

On arrival, the patient had a temperature of 38.1℃ (100.6°F), respiration rate of 48/min, pulse rate of 180/min, and a blood pressure reading of 100/50mmHg (50-75th percentile for her age). On physical examination, she exhibited tachypnea, chest wall retraction, and cyanosis.

Arterial blood gas analysis gave values of pH 7.42, PaO2 29mmHg, PaCO2 30mmHg, and Sa O2 58% (on mask oxygen at a rate of 10L/min).

Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 19400/uL, with neutrophils comprising 73% of total cells. C reactive protein was negative, and other chemistry results were all within normal limits without any abnormal findings in blood and sputum cultures. Test results for respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, influenza, and parainfluenza were all negative.

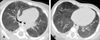

The chest radiograph revealed bilateral ground glass opacity, while the chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed bilateral ground glass opacities with some mosaic perfusion patterns, and emphysematous changes in the right middle lobe (RML) and interlobular septal thickening (Fig. 1).

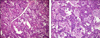

The patient developed respiratory distress requiring intubation and was transferred to our intensive care unit. We diagnosed the interstitial pneumonia and treated her with IV antibiotics, IV dexamethasone, and ventilator care. By the 18th hospital day, her clinical symptoms had improved and she was extubated successfully. On day 27 of her hospital stay, the patient underwent an open lung biopsy to establish a definitive diagnosis. The biopsy of the lung suggested CPI, due to the presence of cellular interstitial and airspace processes with a relative paucity of inflammatory cells, alveolar septal thickening in association with type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, and an increased number of airspace macrophages (Fig. 2).

From day 28 onward, her oxygen dependency decreased, and radiologic findings improved. She discharged on day 50, and has shown no problems in follow-up visits in the outpatient clinic.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is rare in children, and the classification schemes used for adult disorders have generally been applied to these childhood variants.2 Interstitial lung diseases, including CPI, share common clinical, physiologic, and radiolographic features.2 But, its pathological features differs from the classical patterns of interstitial lung disease (desquamative interstitial pneumonia, usual interstitial pneumonia, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia) seen in adults and children.1,3,7

CPI was first described by Katzenstein et al. in 1995.1 The histologic features of CPI are a striking combination of interstitial and air-space processes in which the inflammatory cells are inconspicuous. Interstitial changes observed include a combination of diffuse thickening alveolar septa associated with hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes, and primitive mesenchymal cells within the alveolar septa. Alveolar changes include alveolar exudates containing an increased number of macrophages and foci of pulmonary proteinosis-like material found in air spaces.1-3

The radiologic features of CPI correlate well with their pathologic appearance.4 Typical chest radiograph findings of CPI include ground-glass densities, consolidation, volume loss, and hyperinflation.4

Kavantzas et al. commented that many infant deaths previously attributed to other types of interstitial pneumonia or unknown etiology, may be due to CPI.3 When treating infants and very young children with progressive lung disease, CPI should be considered in the differential diagnosis.4 A lung biopsy may be required and helpful in establishing a diagonosis of CPI because the radiologic and clinical patterns are non-specific and overlap with that of other lung diseases.4

Treatment of CPI uses high-dose steroids, and in refractory cases, hydroxylchloroquine and other immunosuppressive drugs, or ultimately lung transplantation.5

The prognosis of this entity has been poor, and mortality rate of CPI is very high, even with treatment.1,2,6 In Katzenstein's study, 2 of the 6 patients whose outcome was known died within 3 months of the onset of symptoms, and another patient underwent lung transplantation.1 Fisher et al. had previously described a similar process in 8 children, although the majority were much older.7

An autopsy study of 12 cases of CPI revealed an age of onset of 1-9 months, with an ultimate fatal outcome despite treatment.3

In summary, we report a case of a 3 month old girl diagnosed with CPI from an open lung biopsy who improved after proper treatment.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Katzenstein AL, Gordon LP, Oliphant M, Swender PT. Chronic pneumonitis of infancy. A unique form of interstitial lung disease occurring in early childhood. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995. 19:439–447.

2. Nicholson AG, Kim H, Corrin B, Bush A, du Bois RM, Rosenthal M, et al. The value of classifying interstitial pneumonitis in childhood according to defined histological patterns. Histopathology. 1998. 33:203–211.

3. Kavantzas N, Theocharis S, Agapitos E, Davaris P. Chronic pneumonitis of infancy. An autopsy study of 12 cases. Clin Exp Pathol. 1999. 47:96–100.

4. Abe K, Kamata N, Okazaki E, Moriyama S, Funata N, Takita J, et al. Chronic pneumonitis of infancy. Eur Radiol. 2002. 12:S155–S157.

5. Olsen E ØE, Sebire NJ, Jaffe A, Owens CM. Chronic pneumonitis of infancy: high-resolution CT findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2004. 34:86–88.

ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download