Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the relationship between depressive symptoms and health care costs in outpatients with chronic medical illnesses in Korea, we screened for depressive symptoms in 1,118 patients with a chronic medical illness and compared the severity of somatic symptoms and health care costs.

Patients and Methods

Data were compared between outpatients with depressive symptoms and those without depressive symptoms. Depression and somatic symptoms were measured by Zung's Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-15, respectively. We also investigated additional data related to patients' health care costs (number of visited clinical departments, number of visits made per patients, and health care costs). A total of 468 patients (41.9%) met the criteria for depressive disorder.

Results

A high rate of severe depressive symptoms was found in elderly, female and less-educated patients. A positive association between the severity of somatic symptoms and depressive symptoms was also identified. The effects of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic illnesses on three measures of health services were assessed by controlling for the effects of demographic variables and the severity of somatic symptoms. We found that the effects of depressive symptoms on the number of visited departments and number of visits made per patients were mediated by the severity of somatic symptoms. However, for health care costs, depressive symptoms had a significant main effect. Furthermore, the effect of gender on health care costs is moderated by the degree of a patient's depressive symptoms.

Numerous studies have addressed the risks of depression developing in patients with medical illnesses. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborative Study,1 depression was 4.7 times more likely to develop in patients with one chronic medical illness and 6 times more likely in patients with two or more chronic medical conditions than in normal, healthy persons. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis,2 asthma,3 diabetes,4-6 myocardial infarction,7 and cerebrovascular accident8,9 have been shown to have significantly more depressive symptoms.

The comorbidity of depression and medical illness imposes an even greater burden on health care services. Several studies have examined the increase in the use of general medical services in patients with specific chronic medical illnesses. Included in this group were studies of patients with heart failure,10 diabetes11 and arthritis.12 These studies reported that depression was associated with increased use or cost of general medical services. Also, depression in primary care patients,13-15 high utilizers of general medical services,16 and Medicare health maintenance organization (HMO) patients17 was associated with a significant increase in overall health care costs.

Despite increased attention on the comorbidity of depression and medical illness, little information is available on the prevalence of depression in Korean patients with chronic medical illnesses and the ensuing economic burden it poses. The present study firstly examined the prevalence of depressive symptoms in outpatients with chronic medical illnesses in Korea. Then, the associations between depressive symptoms and demographic characteristics were investigated. Furthermore, since patients with depression frequently present with somatic symptoms,18 we additionally examined the association between the depressive symptoms and the severity of the somatic symptoms. Finally, the effects of depressive symptoms in outpatients with chronic medical illnesses on three measures of health services (number of visited clinical departments, number of visits made per patients, and health care costs) were evaluated.

Subjects were 1,534 consecutive outpatients with chronic medical illnesses, aged 20 to 85, who had been treated for at least one year in the Department of Internal Medicine, St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea. A total of 1,254 patients participated in the study, and 280 patients refused to participate (18.3%). We excluded patients with a previous history of psychiatric treatments from the study, because the goal of the present study was to examine the health care costs related to depressive symptoms alone. We also excluded cancer patients because the experience of cancer includes distinct chronological phases, and research has repeatedly revealed a higher prevalence of psychiatric illness in a variety of populations of cancer patients than in those with other medical illnesses.19,20

Since patients with cancer and/or patients with a previous history of psychiatric treatments were excluded from the study, the data of 136 patients were deleted from the sample, so the data of 1,118 patients were ultimately analyzed. Subjects were relatively chronically ill patients who had been treated for at least one year for endocrine diseases (e.g. diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease; n = 195), rheumatic diseases (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); n = 173), gastrointestinal diseases (e.g. gastric ulcer, inflammatory bowel disease; n = 185), cardiovascular diseases (e.g. hypertension, cardiac arrythmia; n = 196), renal diseases (e.g. chronic renal failure, diabetic nephropathy; n = 184), or pulmonary diseases (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma; n = 185). Data were obtained by individual interviews from February 2004 through June 2004.

Zung's Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) was used to screen the patients for depressive symptoms.21 The SDS is a self-rating scale containing 20 questions about depressive symptoms. We used a Korean version of the SDS which was translated by Shin et al.22 Each item is anchored on a 4-point scale (1 = no to 4 = always). In SDS, an adjusted score of less than 49 points is regarded as indicating a normal state, and 50 to 59 points, 60 to 69 points, and over 70 points indicate mild, moderate, and severe depressive symptoms, respectively.22

The Patient Health Questionnaire somatic symptom severity scale (PHQ-15) was used to measure the severity of somatic symptoms in subjects.23 PHQ-15 is also a self-rating scale containing 15 questions. All items are anchored on a 3-point scale (0 = no pain to 2 = severe pain). A score of 0 to 4 points on the PHQ-15 indicates minimal somatic symptom severity, and 5 to 9 points, 10 to 14 points, and 15 to 30 points indicate low, medium and high somatic symptom severities, respectively.

We also obtained additional data related to patients' health care services during the year of 2003, including health care costs, number of visited clinical departments, and number of visits made per patients in any Korean hospital. Computerized data were provided by the National Health Insurance Corporation of Korea.

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after a full description of the objectives and procedures of the present study. The ethical committee of St. Mary's Hospital approved this study.

The association between depressive symptoms and somatic symptoms was analyzed by using the Kruakal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significances of the differences in health care costs, numbers of visited clinical departments, and the difference in numbers of visits between patients with depressive symptoms and those without any symptoms were assessed by regressions which incorporated demographic variables and the severity of somatic symptoms as covariates. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS PC version 6.0.

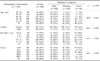

Of the 1,118 patients with chronic medical illnesses, 468 (41.9%) were categorized as having significant depressive symptoms [242 mild depression (21.6%), 142 had moderate depression (12.7%), and 84 suffered from severe depression (7.5%)]. Table 1 presents demographic information for the four patient groups after stratification for the severity of depressive symptoms, and it includes patients without significant depressive symptoms. Comparisons of demographics across the four patient groups revealed that depressive symptoms were associated with all demographic data. In particular, the prevalence of mild depressive symptoms was higher for younger patients, while the prevalence of moderate or severe depressive symptoms was higher for older patients (χ2 = 46.4, p < 0.001). Female patients were also more likely to show depressive symptoms than male patients (χ2 = 49.1, p < 0.001). With regard to education level, less educated patients were more likely to develop moderate or severe depressive symptoms (χ2 = 67.9, p < 0.001). Finally, patients who had endocrine diseases or cardiovascular diseases were more likely to show severe depressive symptoms (χ2 = 96.5, p < 0.001).

To evaluate the association between depressive symptoms and somatic symptoms, we used a Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA to analyze the severity of the somatic symptoms across four groups (normal, mild, moderate, severe depression). Table 2 reveals that the severity of somatic symptoms differed significantly across the four groups (χ2 = 322.7, p < 0.001). The severe depressive group showed significantly higher somatic symptoms than the mild and moderately depressive groups. However, the mild and moderately depressive groups had significantly higher somatic symptoms than the normal controls.

Table 3 shows three measures of health services according to the degree of depressive symptoms. ANOVA results (Table 3) suggest strong evidence for the association between depressive symptoms and increased use of health services at all levels of medical comorbidity (number of visited clinical departments, F = 2.9, p = 0.032; number of visits made per patients, F = 6.0, p < 0.001; healthcare costs, F = 3.9, p = 0.009). Post-hoc analyses, which are presented at the bottom of Table 3, display homogeneous subsets for each dependent variable. However, attention should be paid to interpreting the results in Table 3, since, as we have seen in Tables 1 and 2, depressive symptoms were associated with demographic characteristics and the severity of somatic symptoms. Therefore, to appropriately assess the influence of depressive symptoms on the use of health services, the effects of demographic variables and the severity of somatic symptoms should be controlled. Tables 4-6 present the results of regressions in which demographic variables and the severity of somatic symptoms were included as covariates.

The regression model for the number of visited departments (Table 4) was significant (F = 13.8, p < 0.001) and gender and age turned out to be significant, as well. The number of visited departments was greater for females and elderly patients. Interestingly, the severity of somatic symptoms was also significant, indicating that the higher number of visited departments found in the more depressed group of patients was due to the more severe somatic symptoms in these groups. This relationship was repeated in the regression model for number of visits made per patients (Table 5; F = 19.8, p < 0.001). In Table 5, age and education turned out to be significant. The number of visits made per patients was greater for the elderly and the less-educated. Again, the severity of somatic symptoms was also significant, revealing the mediating role of the severity of somatic symptoms between depressive symptoms and number of visits made per patients. Standardized coefficients (Beta) in Table 5 indicate that age (Beta = 0.198) and the severity of somatic symptoms were more important variables in predicting patients' numbers of visits.

In a regression model for health care costs (Table 6), gender, education and depressive symptoms (at α = 10%) were significant, while the severity of somatic symptoms was not. Gender, years of education and depressive symptoms were associated with significant increases in health care costs. We further investigated possible interactions among independent variables. Interaction terms were not significant for number of visited departments or number of visits. However, for health care costs, only the interaction between gender and depressive symptoms was significant (Table 6(b)), indicating that health care costs were highest for female patients with depressive symptoms.

This study revealed that the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Korean patients with chronic medical illnesses was high (41.9%). This prevalence is consistent with that found in previous research1,24 which reported 54.9%, 51.3%, 39.0%, 35.1%, and 33.8% prevalence rates in patients with cardiovascular diseases, rheumatic diseases, endocrine diseases, respiratory diseases, or gastrointestinal diseases, respectively.

For early diagnosis and treatment of patients with depression, it is very important to know that some patients with certain demographic characteristics are more vulnerable to depression. Previous studies have found that age,25 gender26 and marital status27 are associated with depression. This tendency is also maintained for Korean patients with chronic medical illnesses. A high prevalence rate of severe depressive symptoms was found in elderly and female patients. In addition, we found that the patients with less education tended to show severe depressive symptoms. This could be related to self-efficacy issues. Francis et al.28 reported that there was a significant increase in patients' self-efficacy and a significant decrease in depression symptoms after a one-year adult literacy program.

To evaluate the effects of depressive symptoms on health care costs in patients with chronic illnesses, three measures of health services (number of visited clinical departments, number of visits, and health care costs) were selected. The major contribution of this study is that the effects of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic illness on three measures of health services were assessed by controlling for the effects of demographic variables and the severity of somatic symptoms. We found that the effects of depressive symptoms on the number of visited departments and the number of visits were mediated by the severity of somatic symptoms. However, for health care costs, depressive symptoms had a significant main effect, indicating that they are associated with significant increases in health care costs. Furthermore, there exists a significant interaction between gender and depressive symptoms. This interaction term can be interpreted as a moderating effect of depressive symptoms on health care costs. In other words, the effect of gender on health care costs is moderated by the degree of a patient's depressive symptoms, such that the magnitude of the effect is greater when a patient's depressive symptom is severe than it is when he/she is normal.

However, this study had some limitations. The socio-economic characteristics of patients, which were not included in our analyses, can influence their use of health care services. Depressive symptoms can be caused by the severity of chronic illness. Therefore, the degree of chronic illness needs to be considered in future studies. Other limitations of this study include a cross-sectional design. We were not able to distinguish somatic symptoms due to depressive symptoms from somatic symptoms due to chronic medical illnesses. We also did not examine the different departments that patients visited. Visiting the psychiatric department or other departments such as the surgical department would reflect different aspects of patients' conditions. In addition, data provided by the National Health Insurance Corporation of Korea may not appropriately reflect patients' use of health care services, since patients with chronic illnesses, especially in the case of rheumatic diseases, visit alternative medicine or naturopathic doctors more often. Moreover, this study included a single university hospital in Seoul, Korea. Therefore, the results of this study would not necessarily generalize to other regions.

In summary, depression is frequently comorbid with other medical conditions. Despite its high prevalence, depression often goes undetected, imposing an even greater burden on patients' daily lives and on health care services. This study showed that chronic illness patients with depressive symptoms were more likely to incur severe somatic symptoms, more clinical treatments and higher health care costs than are patients without depressive symptoms. Therefore, there is clearly a need for increased recognition and treatment of depression for Korean patients with chronic medical illnesses.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Sartorius N, Ustün TB, Lecrubier Y, Wittchen HU. Depression comorbid with anxiety: results from the WHO study on psychological disorders in primary health care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996. 30:38–43.

2. Abdel-Nasser AM, Abd El-Azim S, Taal E, El-Badawy SA, Rasker JJ, Valkenburg HA. Depression and depressive symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis patients: an analysis of their occurrence and determinants. Br J Rheumatol. 1998. 37:391–397.

3. Afari N, Schmaling KB, Barnard S, Buchwald D. Psychiatric comorbidity and functional status in adult patients with asthma. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2001. 8:245–252.

4. Anderson RJ, Freeland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001. 24:1069–1078.

5. Gary TL, Crum RM, Cooper-Patrick L, Ford D, Brancati FL. Depressive symptoms and metabolic control in African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000. 23:23–29.

6. Lloyd CE, Dyer PH, Barnett AH. Prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety in a diabetes clinic population. Diabet Med. 2000. 17:198–202.

7. Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Juneau M, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Gender, depression, and one-year prognosis after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 1999. 61:26–37.

8. Kotila M, Numminen H, Waltimo O, Kaste M. Post-stroke depression and functional recovery in a population-based strike register. The Finnstroke Study. Eur J Neurol. 1999. 6:309–312.

9. Kauhanen M, Korpelainen JT, Hiltunen P, Brusin E, Mononen H, Määttä R, et al. Post-stroke depression correlates with cognitive impairment and neurological deficits. Stroke. 1999. 30:1875–1880.

10. Sullivan M, Simon G, Spertus J, Russo J. Depression-related costs in heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2002. 162:1860–1866.

11. Ciechanowski P, Katon W, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000. 160:3278–3285.

12. Vali F, Walkup J. Combined medical and psychological symptoms: impact on disability and health care utilization of patients with arthritis. Med Care. 1998. 36:1073–1084.

13. Pearson SD, Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Manning WG, Helstad CP, Henk HJ. Depression among high utilizers of medical care. J Gen Intern Med. 1999. 14:461–468.

14. Simons G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995. 152:352–357.

15. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Barlow W. Health care costs of primary care patients with recognized depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995. 52:850–856.

16. Henk HJ, Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW. Medical costs attributed to depression among patients with a history of high medical expenses in a health maintenance organization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996. 53:899–904.

17. Unützer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, Grembowski D, Walker E, Rutter C, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. A 4-year prospective study. JAMA. 1997. 277:1618–1623.

18. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An International study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 1999. 341:1329–1335.

19. Sellick SM, Crooks DL. Depression and cancer: an appraisal of the literature for prevalence, detection, and practice guideline development for psychological interventions. Psychooncology. 1999. 8:315–333.

20. Massie MJ, Popkin MK. Holland J, editor. Depressive Disorders. Psycho-oncology. 1998. New York: Oxford University Press;518–554.

22. Shin HC, Kim CH, Park YW, Cho BL, Song SW, Yun YH, et al. Validity of Zung's self-rating depression scale: Detection of depression in primary care. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2000. 21:1317–1330.

23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002. 64:258–266.

24. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989. 262:914–919.

25. Chisholm D, Diehr P, Knapp M, Patrick D, Treglia M, Simon G. LIDO Group. Depression status, medical comorbidity and resource costs. Evidence from an international study of major depression in primary care (LIDO). Br J Psychiatry. 2003. 183:121–131.

26. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Henk HJ. Effect of primary care treatment of depression on service use by patients with high medical expenditures. Psychiatr Serv. 1997. 48:59–64.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download