Abstract

Teratomas represent 0.5% of all intracranial tumors. These benign tumors contain tissue representative of the three germinal layers. Most teratomas are midline tumors located predominantly in the sellar and pineal regions. The presence of a teratoma in the cavernous sinus is very rare. Congenital teratomas are also rare, especially those of a cystic nature. To our knowledge, this would be the first case report of a congenital, rapidly growing cystic teratoma within the cavernous sinus. A three-month-old boy presented with a past medical history of easy irritability and poor oral intake. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) scan of the head disclosed a large expanding cystic tumor filling the right cavernous sinus and extending into the pterygopalatine fossa through the foramen rotundum. These scans also demonstrated a small area of mixed signal intensity, the result of the different tissue types conforming to the tumor. Heterogeneous enhancement was seen after the infusion of contrast medium. However, this was a cystic tumor with a large cystic portion. Thus, a presumptive diagnosis of cystic glioma was made. With the use of a right frontotemporal approach, extradural dissection of the tumor was performed. The lesion entirely occupied the cavernous sinus, medially displacing the Gasserian ganglion and trigeminal branches (predominantly V1 and V2). The lesion was composed of different tissues, including fat, muscle and mature, brain-like tissue. The tumor was completely removed, and the pathological report confirmed the diagnosis of a mature teratoma. There was no evidence of recurrence. Despite the location of the lesion in the cavernous sinus, total removal can be achieved with the use of standard microsurgical techniques.

Germ cell tumors make up 0.4-3.1% of all intracranial tumors. They can be classified as germinomatous (germinoma) and nongerminomatous tumors (teratoma, mature teratoma, malignant teratoma, endodermal sinus tumor, and choriocarcinoma). Mixed-forms exist as well.

Teratomas represent 0.5% of all intracranial tumors. These benign tumors contain tissue representative of the three germinal layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). Most teratomas are midline tumors located predominantly in the sellar and pineal regions. Less often, they occupy the lateral ventricles or the posterior fossa in the cerebellopontine angle. One of the rarest locations is the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus; only three pure intracavernous teratomas have been reported.1-3 Here, we present a rare case of a cystic congenital mature teratoma arising within the cavernous sinus of a three-month-old boy. This case is especially interesting in light of the rapid growth of the cystic teratoma.

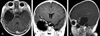

In November 2005, a three-month-old boy was admitted to our department with a three-week history of easy irritability and poor oral intake. He had an uneventful vaginal delivery in August 2005. However, there was a mild scalp bulge, suspicious of a cephalhematoma. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed a widened foramen rotundum and an abnormal density in the right cavernous sinus (Fig. 1). The boy was discharged home since he did not exhibit any abnormal neurologic signs. Two months later, the boy presented again with poor oral intake, easy irritability, and insomnia during the night. An MRI scan of the head showed a large cystic lesion filling the entire middle cranial fossa, compressing the right temporal lobe. There was also evidence of a relatively small solid portion of varying signal intensity; this area enhanced heterogeneously after the administration of intravenous contrast medium. The lesion was also in the pterygopalatine fossa, and the two areas communicated through a more widened foramen rotundum as compared to the previous study. The right cavernous sinus was occupied entirely by the lesion, with medial displacement of the internal carotid artery (Fig. 2). The presumptive diagnosis was cystic glioma.

The patient was subsequently referred to our care. When he arrived in our department, the patient again presented with easy irritability. Clinical examination revealed no definitive neurological abnormalities except cranial asymmetry with a prominent temporal squama on the right side. No other cranial nerve abnormalities were noted. The results of the motor and sensory examinations were normal.

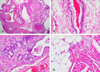

A right frontotemporal approach was used. After the dura was opened, a large lesion was found occupying the temporal fossa and elevating the basal dura mater. Only a remnant temporal lobe, which was displaced dorsocaudally, was identified. First, a small hole was made, and the clear yellow fluid in the cyst was aspirated. The basal dura mater was then incised inferiorly. The tumor contents, readily apparent at the anteromedial area of the temporal fossa, consisted of fat tissue, nerve-like tissue, and other unidentifiable tissues. The dura was firmly adhered to the tumor capsule, and it had to be removed along with the tumor. Using the microscissor and dissector, we were able to detach tumor from dura with strenuous effort. When we approached the medial edge of the tumor, we could identify the oculomotor nerve piercing the dura as it entered the cavernous sinus. Cranial nerve IV and the trigeminal nerve (V1 and V2) roots could not be identified on the medial side of the tumor. As the dissection proceeded laterally, we found that the floor of the middle fossa and the anterosuperior surface of the petrous bone were eroded. The root of cranial nerve V was then identified; it appeared to be elongated. The Gasserian ganglion was identified, apposing the temporal squama. It is possible that the V1 root might have been traumatized during attempts to remove a portion of the adherent tumor. The tumor exited to the pterygopalatine fossa through the foramen rotundum. V2 and V3 were identified. We tried to remove the tumor through the widened foramen rotundum. Fortunately, the tumor was easily removed. The tumor was excised macroscopically and radically (Fig. 3). When the patient was extubated after the operation, right oculomotor nerve paresis was evident, and a cranial nerve VI palsy was suspected. MRI scans obtained immediately after the operation did not demonstrate any residual tumor (Fig. 4A), and the patient was discharged ten days after the surgery. A pathological examination revealed a mature teratoma consisting of tissue representative of the three germinal layers (Fig. 5 and 6). Five months after the operation, the patient visited our outpatient department. The patient's condition was good, and did not experience any residual cranial nerve paresis that had been evident immediately postoperative. The MRI scan (Fig. 4B) from April 2006 showed no tumor recurrence or postoperative change. The patient will be followed on an outpatient basis, without further treatment.

The tumor was composed of ectoderm, mesoderm and neuroectoderm. A low-power view demonstrated cystic changes (Fig. 5A). Architecturally malformed brain tissue was noted (Fig. 5B). A high-power view showed neurons with laminar distortion and multifocal calcification (Fig. 5C). A multilocular cystic area with lining epithelium was noted (Fig. 6A and B). Scattered glands resembling salivary glands (Fig. 6C), adipose and muscle tissue (Fig. 6D) were seen.

Teratomas are best defined as benign tumors containing representative elements of three germinal layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). Teratomas have been classified according to the histological appearance of the different cell and tissue types within the lesion. Thus, they are classified into three groups: 1) mature teratomas, consisting of fully differentiated tissues representing the three germinal layers; 2) immature teratomas (which are the most frequent), characterized by the presence of cellular populations that retain their embryological features and include more primitive components derived from all or any of the three germinal layers; and 3) malignant teratomas, which can be mature or immature teratomas, and have a malignant component represented by germ cells (atypical teratoma) and embryonal undifferentiated cells.3-5 Our patient would be fall into the first category. This is a rare type of neoplasm, representing only 0.5% of all intracranial tumors.6 However, the incidence increases in a selected population of patients younger than 15 years old. In this group, teratomas represents 2% of all intracranial tumors.7-9 The tumor incidence in children younger than 15 years of age is four times that of the general public. However, congenital intracranial teratomas are extremely rare, and are usually extensive when first identified. In a review of numerous neonatal and childhood teratomas, Wakai6 noted two different peak incidence age groups: younger than two months, and 10 years of age. The presentation of a patient with a teratoma after the first two decades of life is exceptional.

Congenital teratomas are most commonly found in the sacrococcygeal region, but they can also occur in the neck, mediastinum, and intracranial regions. Being midline lesions, these tumors usually involve the pineal gland, suprasellar region, quadrigeminal plate, walls of the third ventricle, and cerebellar vermis. Other non-midline sites that have been described include the basal ganglia, cerebellopontine angle, cavernous sinus, lateral ventricle, and (rarely) the fourth ventricle.3,10,11

Canan et al.12 suggested three categories for teratoma classification based on radiographic features. Our patient fell into the more localized, less extensive category. According to a review by Lipman et al., cystic formation is a common feature of neonatal intracranial teratomas.13 At first, our patient presented with a solid intracavernous tumor. For about two months postnatal, the tumor grew rapidly and formed a large cyst, which filled the entire middle cranial fossa. There is no such case like this in the literature.

In 1995, Pikus et al.2 reported the first case of a surgically removed teratoma involving the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. The authors offered an elegant description of the clinical and pathological characteristics of the teratoma, and emphasized the importance of anatomic knowledge of the cavernous sinus in order to achieve total lesion resection with minimal neurological deficits (i.e., injury to cranial nerves).

A second case was recently reported by Becherer et al.1 The authors exhaustively reported clinical, diagnostic, and pathological findings of the tumor, and concluded that teratomas are resectable lesions with a low morbidity rate (defined mainly by the extent of cranial nerve dysfunction).

Another case reported by Tobias3 involved a 14-year-old boy. In the report, the author stated that the giant teratoma in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus could be totally removed using standard microsurgical techniques.

In our case, the tumor was large and cystic. The cranial nerves were pushed laterally and medially so the tumor could be easily removed. The cystic portion was removed when we approached the cavernous sinus, and the tumor was detached from the tightly adherent dura. Fortunately, the tumor was not as adhered to cranial nerves as we expected.

Mature teratomas are well-differentiated lesions that are usually lobulated and tend to adhere firmly to neighboring tissues.14 Microscopically, they consist of solid and cystic portions of squamous epithelium with keratin debris.1 They contain fully mature tissue of ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal origin. The most common tissues found in teratomas are skin and appendages, cartilage, adipose tissue, muscle strands, glioneural tissue, and retinal and pigmented ocular tissue.9,15 Our patient's teratoma consisted of mature brain tissue, fat, and muscle (Fig. 5).

A one-year survival rate of 7.2% has been reported in one large study.6 Surgical treatment has been seldom reported due to the high frequency of fetal and postnatal death. Prenatal ultrasonography and fetal MRI permit early detection, diagnosis, and evaluation of intracranial tumors.16 Hunt et al. reviewed 19 cases involving congenital teratomas,5 reporting that the most frequent surgical procedure was subtotal excision, and that the average age at surgery was approximately five weeks. Of the two survivors, one underwent surgery at less than two weeks of age; the other at eight weeks of age. The site of the tumor and its size appeared to influence the outcome. Successful cases involved favorably situated small tumors (3-5cm). In the literature, these tumors were considered mixed with immature teratomas, and the tumors were mainly large and solid. As such, surgical morbidities and mortalities were high, and perioperative deaths and morbidities were not uncommon. In our case the tumor was mainly cystic and consisted of only the mature teratoma components. In spite of the location of the lesion in the cavernous sinus, total removal can be achieved with the use of standard microsurgical techniques. Knowledge of microanatomy is essential in treating intracavernous pathology. To our knowledge, this is the first case report involving a rapidly growing mature cystic teratoma within the cavernous sinus. At five months after operation, the patient was in good condition and showed no evidence of tumor recurrence. Since the standard treatment for the mature teratomas is complete removal of the tumor, our patient in theory would not require any further treatment. However, since the patient was very young when he presented, the possibility of tumor recurrence still exists. Also this tumor had a potency of the distant metastasis17 and metachronous occurrence of the mixed germ cell tumor18 because the germ cell is a totipotent itself. The patient should be followed in an outpatient clinic at regular intervals.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1A preoperative brain CT scan at birth shows a mass lesion in the right cavernous sinus and pterygopalatine fossa. (A) A brain CT without contrast enhancement shows a faint mass lesion in the right cavernous sinus. (B) A brain CT with contrast enhancement shows a more precise mass lesion in the right cavernous sinus. |

| Fig. 2Preoperative brain MRI shows a large cyst and solid tumor within the right cavernous sinus filling the middle cranial fossa and pushing the temporal lobe superiorly. (A) A T1-weighted axial image shows the solid component of the tumor anteromedially. (B) The lateral wall of the cavernous sinus was pushed superomedially by the mass. The superior portion of the cavernous sinus and right cavernous portion of the carotid artery were pushed medially. (C) A T1-weighted sagittal image shows a cystic mass in the pterygopalatine fossa. |

| Fig. 3The operation was performed through a right frontotemporal craniotomy. The tumor consisted mainly of a cystic portion as well as a relatively small solid portion within the cavernous sinus. After aspiration of fluid from the cystic cavity, the dura was incised in a curvilinear fashion (A) The tumor was pulled from the pterygopalatine fossa through the foramen rotundum (B, ★). The tumor in the pterygopalatine fossa was easily removed through the foramen rotundum because it was cystic and not adhered to adjacent structures. |

| Fig. 4(A) A postoperative MRI scan (T1-weighted axial and coronal image with Gadolinium enhancement), which was taken 48 hours after the operation, shows complete tumor removal. (B) A postoperative brain MRI scan shows total tumor removal. |

References

1. Becherer TA, Davis DG, Hodes JE, Warf BC. Intracavernous teratoma in a school-aged child. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999. 30:135–139.

2. Pikus HJ, Holmes B, Harbaugh RE. Teratoma of the cavernous sinus: case report. Neurosurgery. 1995. 36:1020–1023.

3. Tobias S, Valarezo J, Meir K, Umansky F. Giant cavernous sinus teratoma: a clinical example of a rare entity: case report. Neurosurgery. 2001. 48:1367–1371.

4. Shaffrey ME, Lanzino G, Lopes MB, Hessler RB, Kassell NF, VandenBerg SR. Maturation of intracranial immature teratomas. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1996. 85:672–676.

5. Hunt SJ, Johnson PC, Coons SW, Pittman HW. Neonatal intracranial teratomas. Surg Neurol. 1990. 34:336–342.

7. Di Rocco C, Iannelli A, Ceddia A. Intracranial tumors of the first year of life. A cooperative survey of the 1986-1987 Education Committee of the ISPN. Childs Nerv Syst. 1991. 7:150–153.

8. Nanda A, Schut L, Sutton LN. Congenital forms of intracranial teratoma. Childs Nerv Syst. 1991. 7:112–114.

9. Sano K. Pathogenesis of intracranial germ cell tumors reconsidered. J Neurosurg. 1999. 90:258–264.

10. Keene DL, Hsu E, Ventureyra E. Brain tumors in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Neurol. 1999. 20:198–203.

11. Lesoin F, Jomin M. Direct microsurgical approach to intracavernous tumors. Surg Neurol. 1987. 28:17–22.

12. Canan A, Glsevin T, Nejat A, Tezer K, Sule Y, Meryem T, et al. Neonatal intracranial teratoma. Brain Dev. 2000. 22:340–342.

13. Lipman SP, Pretorius DH, Rumack CM, Manco-Johnson ML. Fetal intracranial teratoma: US diagnosis of three cases and a review of the literature. Radiology. 1985. 157:491–494.

14. Matsutani M, Sano K, Takakura K, Fujimaki T, Nakamura O, Funata N, et al. Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: a clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg. 1997. 86:446–455.

15. Jennings MT, Gelman R, Hochberg F. Intracranial germ-cell tumors: natural history and pathogenesis. J Neurosurg. 1985. 63:155–167.

16. Im SH, Wang KC, Kim SK, Lee YH, Chi JG, Cho BK. Congenital intracranial teratoma: prenatal diagnosis and postnatal successful resection. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003. 40:57–61.

17. Kang MK, Ahn YC, Park JO, Han J, Lee KS. Lung metastasis from an immature teratoma of the nasal cavity masquerading a small cell carcinoma of the lung. Yonsei Med J. 2006. 47:571–574.

18. Shim KW, Kim DS, Choi JU. Mixed or metachronous germ cell tumor? Childs Nerv Syst. 2007. 23:713–718.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download