Abstract

We report a rare case of traumatic abdominal wall hernia (TAWH) caused by a traffic accident. A 47-year-old woman presented to the emergency room soon after a traffic accident. She complained of diffuse, dull abdominal pain and mild nausea. She had no history of prior abdominal surgery or hernia. We found a bulging mass on her right abdomen. Plain abdominal films demonstrated a protrusion of hollow viscus beyond the right paracolic fat plane. Computed tomography (CT) showed intestinal herniation through an abdominal wall defect into the subcutaneous space. She underwent an exploratory surgery, followed by a layer-by-layer interrupted closure of the wall defect using absorbable monofilament sutures without mesh and with no tension, despite the large size of the defect. Her postoperative course was uneventful.

Traumatic abdominal wall hernia remains a rarely reported event, despite the high prevalence of blunt abdominal trauma.1,2 A review of English literature on this subject showed approximately 50 reported cases since the first report in 1906.1,3 TAWHs are generally categorized into three major types: (1) a small abdominal wall defect caused by low-energy trauma with small instruments, e.g., bicycle handlebars, (2) a larger abdominal wall defect caused by high-energy injuries, and (3) rarely, intraabdominal herniation of the bowel caused by deceleration injuries.2 We present a rare case of a large TAWH with a bowel herniation through a defect after a high-energy motor vehicle accident. The TAWH was successfully managed by layer-by-layer, tension-free repair with absorbable suture materials and without mesh, even though the defect size was large. The special aspects of the TAWH treatment are discussed.

A 47-year-old woman presented to the emergency room soon after a traffic accident. We investigated the details of the accident and found that she had been hit by a one-ton truck and subsequently fell to the ground from the road shoulder, a fall of five feet. Upon arrival at the emergency room, she was fully conscious but her vital signs were fluctuating. She complained of diffuse, dull, abdominal pain and mild nausea. She had a history of hypertension and had been on medications. There was no history of prior abdominal surgery or hernia.

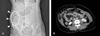

Her initial pulse rate was 74 beats/min and systolic blood pressure 90mmHg. Upon physical examination, her right abdomen was found to have a bulging mass without definite ecchymosis. She felt mild tenderness and rebound tenderness over the protrusion, but no muscle guarding or generalized tenderness over the whole abdomen. We suspected the abdominal protrusion to be caused by a fascial disruption, although the demarcation could not be clearly delineated by physical examination. The bowel sounds were normal. Initial laboratory studies showed anemia (hemoglobin, 9.2g/dL), elevated liver enzymes(AST/ALT, 707/483U/L) and an elevated serum glucose level (261mg/dL), but other laboratory findings including pancreatic and heart enzymes were nonspecific. Chest radiographs showed left rib fractures (8th and 9th). Plain abdominal radiographs demonstrated a lateral protrusion of hollow viscus beyond the right paracolic fat plane (Fig. 1A). Computed tomography showed intestinal herniation through an abdominal wall defect into the subcutaneous space (Fig. 1B) and a small amount of fluid collected in the left pleural cavity, suggesting a hemothorax. CT also showed findings suggestive of liver and spleen laceration but there was not a copious amount of blood within the abdominal cavity. After an initial resuscitation, the patient was taken to the operating theater for an exploratory laparotomy. The peritoneal cavity was entered through a midline incision. Upon intraabdominal exploration, there was no active bleeding from the lacerated liver or spleen. The small bowel and right colon were herniated into the subcutaneous fat plane through a right abdominal wall defect, where components of fascia, muscles, and peritoneum were all torn apart, forming a huge defect (Fig. 2A). There was no perforation or ischemic change of the herniated viscus. After reduction of the herniated content back into the peritoneal cavity, a layer-by-layer interrupted closure from the external oblique muscle components inwards to the laparotomy incision was accomplished using absorbable monofilament sutures (Fig. 2B-D). As shown in Fig. 2B, the margin of the TAWH defect was viable and relatively fresh without necrotic fragments of the muscular component. No additional debridement was needed in this case. The visualization of the hernia defect was good enough to allow layer by layer closure of the TAWH without any technical difficulties. The lacerations of the liver and spleen were secured by the fibrin glue spray to prevent rebleeding. Her postoperative course was uneventful. Neither recurrence of the hernia nor weakness of the repaired abdominal wall layers was identified on the follow-up CT taken 6 months after the surgery (Fig. 3).

Traumatic abdominal wall hernia (TAWH) is produced by a sudden application of blunt force that is insufficient to penetrate the skin but strong enough to disrupt the muscle and fascia.4 TAWH resulting from blunt trauma is relatively rare. In 1980, Dimyan was the first to refer to "handlebar hernia" to describe a traumatic inguinal hernia from a motorcycle handlebar injury.5

TAWH can be defined as posttraumatic when it appears immediately after injury with evident signs of trauma at the initial presentation and the absence of peritoneal sac and skin penetration.6-8 The location of the defect is usually discovered at anatomically weak points in the lateral to rectus sheath, lower abdomen, and inguinal lesion.9 There is no conclusive classification system for TAWH. Nevertheless, categorization is generally based on either the defect size and location or the intensity and mechanism of injury force.2,10-12 Wood et al.2 classified TAWHs into three major types. The first is sustained from a high-energy injury such as a motor vehicle accident or a fall from a height. The fascial defect is generally large. Coexisting intra-abdominal visceral injury is common and depends upon the location of the herniation. The second type is caused by low-energy injuries such as bicycle handlebar impact. In this type of hernia, associated intra-abdominal injuries are relatively infrequent.11 The third type is an intraabdominal herniation of the bowel with deceleration injuries. Ganchi et al. classified it into "focal" and "diffuse" types according to the mechanism of injury.10 Focal TAWHs usually result in small hernias and are rarely associated with intra-abdominal injury. The diffuse type, however, results from pressure and shearing injuries and has a high association with significant intra-abdominal injuries (up to two-thirds).1,10 The overall incidence of associated intra-abdominal injuries in TAWH has been reported to be as high as 30%.10 Although supraumbilical and flank hernias have a higher risk of concomitant visceral injuries, infraumbilical lesions are less likely to be associated with intra-abdominal injury.7

CT scanning is the most accurate diagnostic tool for TAWH and should be used for detection of associated intraabdominal injury.4,8,13 Prompt diagnosis, however, must start with a high index of suspicion and be based on the nature, mechanism, and force of the injury. Clinical findings show subcutaneous fluctuant swelling that may or may not reduce. Abdominal bruising and ecchymosis are common.14

There are some surgical approaches for the repair of TAWHs. Debate still remains as to whether midline exploratory laparotomy is needed to rule out intra-abdominal injuries.15 Local exploration through an incision overlying the defect may be an option for small defects caused by low velocity injury, but TAWHs following high-energy trauma should undergo exploratory laparotomy through a midline incision owing to a high prevalence of associated intraabdominal injuries.1,16 Diagnostic laparoscopy seems to be an excellent adjunct in the management of TAWHs. In the event of a negative diagnostic laparoscopy, one can repair the hernia by the local approach17 and avoid unnecessary general abdominal exploration.9

There are also controversies regarding the timing of exploration: immediate versus delayed exploration. Delayed exploration, as well as delays in diagnosis, can lead to some problems such as a bowel strangulation8,18,19 and excessive tension in the primary closure of the defect.20 Some authors have suggested that reconstruction of the abdominal wall defect can be delayed and repaired on an elective basis,16 especially in the focal type TAWH.21 Immediate exploration and repair, however, has generally been accepted as a more favorable choice in the treatment of TAWH.1,2,10,18 Moreover, early repair through midline exploration has been advocated even in the absence of intra-abdominal injuries.2 In our case, early resuscitation took a few hours and the general condition became stable enough for surgical exploration. In our experience, we would suggest that early exploration could give a better chance of successful primary closure without tensions, even in cases where the hernia defects are very large in size.

There are some reports in which mesh repairs have given good results.22,23 Although no prosthetic materials are required for small defects, it may be safer to apply mesh in large hernias, even in cases in which primary closure may be done without it. However, primary mesh repair should be considered only in cases with no hollow viscus injuries, relatively large defects, and the presence of tension for direct closure.13 Interestingly, primary closure of the fascial defect might be a possible option even though TAWH has been associated with concomitant bowel gangrenes or strangulations.1,8,18 We performed the primary repair safely without mesh and with no tension despite the fact that the defect size was large. The follow-up CT in the postoperative 6th month showed neither recurrence nor weakened muscular layers. Primary repair without mesh seems to be adaptable in large sized TAWHs if there is no excessive tension and if precise layer-by-layer approximation is technically possible. It is clear that prosthetic mesh augments the strength and reduces the possibility of recurrence after ventral hernia repair.24 The need for prosthetic mesh, therefore, must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and the surgeon's preference.

In our case, we used absorbable suture material and had no adverse outcomes, although most reports are in favor of non-absorbable suture material. Several previously reported cases showed no drawbacks to using absorbable suture for hernia repair.9,14,25

In summary, surgeons should have a good knowledge of TAWH and concomitant complications although the disease entity is very rare. If possible, an early surgical approach is required in large TAWHs because large defects have a high prevalence of intraabominal injury. We feel that primary repair is feasible, even if the TAWH is large, if a tension-free closure can be obtained by exact layer-by-layer approximation.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Preoperative contrast enhanced CT scans. (A) Initial scout film shows bulging (arrow head) on right side of the abdomen and protrusion (circle) of the intestinal loop beyond the paracolic fat plane. (B) A huge abdominal wall defect without penetration of the skin. Note that the right colon and small bowel are herniated through the defect. |

| Fig. 2Operative findings. (A) Herniation of the small bowel and right colon through the defect. (B) The skin and subcutaneous fat layer were intact but there was a large defect at the peritoneum, muscle and fascia. (C) The external oblique muscle was approximated with the fascia of the lateral rectus. (D) Complete reconstruction of the wall defect was carried out. |

References

1. Lane CT, Cohen AJ, Cinat ME. Management of traumatic abdominal wall hernia. Am Surg. 2003. 69:73–76.

2. Wood RJ, Ney AL, Bubrick MP. Traumatic abdominal hernia: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 1988. 54:648–651.

4. Damschen DD, Landercasper J, Cogbill TH, Stolee RT. Acute traumatic abdominal hernia: case reports. J Trauma. 1994. 36:273–276.

8. Gill IS, Toursarkissian B, Johnson SB, Kearney PA. Traumatic ventral abdominal hernia associated with small bowel gangrene: case report. J Trauma. 1993. 35:145–147.

9. Shiomi H, Hase T, Matsuno S, Izumi M, Tatsuta T, Ito F, et al. Handlebar hernia with intra-abdominal extraluminal air presenting as a novel form of traumatic abdominal wall hernia: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999. 29:1280–1284.

10. Ganchi PA, Orgill DP. Autopenetrating hernia: a novel form of traumatic abdominal wall hernia--case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 1996. 41:1064–1066.

12. Otero C, Fallon WF Jr. Injury to the abdominal wall musculature: the full spectrum of traumatic hernia. South Med J. 1988. 81:517–520.

13. Drago SP, Nuzzo M, Grassi GB. Traumatic ventral hernia: report of a case, with special reference to surgical treatment. Surg Today. 1999. 29:1111–1114.

14. Fraser N, Milligan S, Arthur RJ, Crabbe DC. Handlebar hernia masquerading as an inguinal haematoma. Hernia. 2002. 6:39–41.

15. Perez VM, McDonald AD, Ghani A, Bleacher JH. Handlebar hernia: a rare traumatic abdominal wall hernia. J Trauma. 1998. 44:568.

16. Kubalak G. Handlebar hernia: case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 1994. 36:438–439.

17. Goliath J, Mittal V, McDonough J. Traumatic handlebar hernia: a rare abdominal wall hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004. 39:e20–e22.

18. Mahajna A, Ofer A, Krausz MM. Traumatic abdominal hernia associated with large bowel strangulation: case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2004. 8:80–82.

19. Walcher F, Rose S, Roth R, Lindemann W, Mutschler W, Marzi I. Double traumatic abdominal wall hernia and colon laceration due to a pelvic fracture. Injury. 2000. 31:253–256.

20. Martinez BD, Stubbe N, Rakower SR. Delayed appearance of traumatic ventral hernia: a case report. J Trauma. 1976. 16:242–243.

21. Sahdev P, Garramone RR Jr, Desani B, Ferris V, Welch JP. Traumatic abdominal hernia: report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Emerg Med. 1992. 10:237–241.

22. Vargo D, Schurr M, Harms B. Laparoscopic repair of a traumatic ventral hernia. J Trauma. 1996. 41:353–355.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download