Abstract

Various manifestations of brain involvement for patients with virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome have been reported. Here, we report on the sequential magnetic resonance (MR) findings of acute demyelination of the entire brain with subsequent brain atrophy in a follow-up study of a 25-month-old boy who was admitted with fever and then diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis and EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. We also review other conditions that should be included in the differential diagnosis of this disease.

Hemophagocytic syndrome is characterized by the benign proliferation of histiocytes with the active phagocytosis of red blood cells and tissue infiltration of several organs by histiocytes. This disease manifests in early infancy with fever, hepatosplenomegaly and pancytopenia.1-3 It can be classified into two categories: primary or secondary form. The secondary form may develop as an inappropriate immunologic activation secondary to infection, malignancy or other immunocompromised conditions.1,4,5 Brain involvement may develop in children with primary or secondary hemophagocytic syndrome, and several reports have described its neuroradiologic findings.2,6-10

We present a case of fulminent leukoencephalopathy in a 25-month-old boy with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated hemophagocytic syndrome as one of the unusual manifestations of the disease's brain involvement.

A 25-month-old boy was referred to our hospital with fever and abdominal distension for three days. Prior to admission, he had been treated with antibiotics for three days at an outside hospital, but the fever had not been controlled. He was born at full term without complication, and there was no remarkable family history.

On admission, he was lethargic and his physical examination revealed hepatomegaly and a skin rash covering his whole body. His initial neurologic examination was unremarkable. Blood examinations revealed anemia (hemoglobin, 10.2 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (platelet, 110,000/µL), hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin, 4.1 mg/dL), and serological studies demonstrated positive EBV antibodies. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies showed elevated cell counts (19 WBC/µL and 54 RBC/µL) and an increased protein level (238 mg/dL). A chest radiograph revealed a small right pleural effusion. A bone-marrow biopsy was performed, and hemophagocytic syndrome was diagnosed (Fig. 1). Karyotyping revealed no chromosomal abnormality.

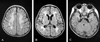

On the 10th hospital day, an episode of generalized tonic-clonic seizure occurred (this was the first incidence), and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain showed diffuse hyperintensity in all of the white matter in both cerebral hemispheres and in the cerebellum, including the corpus callosum and internal capsule, but sparing the subcortical U-fibers (Fig. 2). No enhancing lesions were evident after gadolinium administration.

The patient was treated with steroids, cyclosporine A, etoposide and intrathecal methotrexate injection, and he responded to the therapy without specific neurologic symptoms. A follow-up MR examination on the 66th hospital day showed a partial resolution of hyperintensity in the white matter and the progressive volume loss at the involved site (Fig. 3).

Hemophagocytic syndrome is an unusual and fatal disorder occurring during early infancy that is characterized by the benign proliferation of tissue histiocytes, which is distinct from malignant histiocytosis.1-3 The proposed pathogenesis of this syndrome is defective immunoregulation resulting in the uncontrolled proliferation of activated histiocytes in response to a specific stimulus.4,5 Hemophagocytic syndrome has been known to be associated with infection (virus, bacteria, fungus or parasitic), malignancy, drug exposure, or prolonged immunosupression, and the viruses that have been implicated include EBV, herpes virus and cytomegalovirus. This disease should be distinguished from familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, which is an autosomal recessive condition that presents with similar symptoms and pathologic features in early childhood and runs a more severe course.1,11-13

Histiocytic proliferation characteristically occurs in the liver, spleen and bone marrow, although, in severe cases, it may be seen in other organs such as the brain, lungs and heart. The syndrome generally begins after a short history of a nonspecific viral illness, and commonly results in fever, skin rash, hepatosplenomegaly and pancytopenia. The disease can follow a relapsing and remitting course, or it can progress rapidly to multi-organ failure and death.1-3

CNS involvement has been reported in approximately 30-50% of the cases.6,11 A wide spectrum of neuroradiological findings in patients with hemophagocytic syndrome has been reported, and these findings might be related to the duration or severity of the illness. The major two radiologic findings are: 1) diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement with or without subdural fluid collection, and 2) focal or diffuse T2 hyperintensity with or without parenchymal volume loss of the white matter that usually begins in the peritrigonal regions.2,6-10 These findings are well-correlated with the neuropathologic findings, which have been known to be: 1) diffuse infiltration of the leptomeninges by lymphocytes and histiocytes, 2) dense perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration in all brain regions, and 3) demyelination of the white matter with reactive gliosis, which is predominantly observed in the cerebellum.2,7,8,12,14

The disease could easily be misdiagnosed in many children because its radiographic manifestations are nonspecific and overlap with various infectious, inflammatory and neoplastic disorders.9 It is important to diagnose this condition early and accurately during its course, as effective treatments for hemophagcytic syndrome are now available. Hemophagocytic syndrome is typically managed by treatment with etoposide, steroids, and cyclosporine A, and ultimately with an allogenic bone marrow transplantation from a human leukocyte antigen-matched sibling who is unaffected by the disease.7

We present a case of infectious mononucleosis and EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome with dramatic neuroradiologic findings of confluent T2 hyperintensities affecting the entire white matter of the cerebrum and cerebellum; this resulted in severe atrophy. This finding reflected the acute and extensive demyelination of the entire brain, in addition to widespread tissue infiltration of lymphocytes and erthyrophagocytic histiocytes.

Several conditions should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Acute disseminated encephalomyelopathy (ADEM) is a monophasic, post-infectious or post-vaccinial inflammatory disorder characterized by multifocal white matter lesions with bilateral and asymmetric distribution. There is no doubt that some viruses trigger abnormal immune responses in both conditions, but more fulminent changes develop in the hemophagocytic syndrome. Inherited white matter diseases such as metachromatic leukodystrophy, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, Canavan disease or Alexander disease should also be considered. The differences between these leukodystrophies and hemophagocytic syndrome are the previous delayed-development patterns of the children and a preferential involvement of the subcortical U fibers or the contrast enhancement on imaging findings. Various CNS complications can also occur during treatments including bone-marrow transplants or immunosuppressive therapy. Vascular accidents including ischemia or hemorrhage, superimposed infection, and metabolic or drug-induced encephalopathy should also be considered for these CNS complications.3,6

Whatever the cause, it is important for radiologists to recognize the various MR findings in the evaluation of children with acute neurologic symptoms associated with systemic viral infection. Hemophagocytic syndrome-induced leukoencephalopathy should be also included early in the differential diagnosis of cases with acute encephalopathy showing similar clinical features. Brain MR imagings allow physicians to assess the extent of brain involvement in children with hemophagocytic syndrome, and this may aid in monitoring the response to treatment.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Marrow biopsy section of the patient with EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. (A) There are several macrophages with phagocytosis of erythrocytes and lymphocytes (arrows) on hematoxylin and eosin stains (× 400). (B) Immunohistochemical staining with panmacrophage marker CD68 shows abundant macrophages (× 400).

Fig. 2

(A-C) Axial FLAIR images of the brain show high signal intensities of the entire white matter in both hemispheres, including the corpus callosum, internal capsule and middle cerebellar peduncle, suggesting a fulminent demyelinating process. The preservation of white matter volume without a mass effect and a relative sparing of the subcortical U-fibers are also noted.

References

1. Risdall RJ, McKenna RW, Nesbit ME, Krivit W, Balfour HH Jr, Simmons RL, et al. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: a benign histiocytic proliferation distinct from malignant histiocytosis. Cancer. 1979. 44:993–1002.

2. Schmidt MH, Sung L, Shuckett BM. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children: abdominal US findings within 1 week of presentation. Radiology. 2004. 230:685–689.

3. Forbes KP, Collie DA, Parker A. CNS involvement of virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: MR imaging appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000. 21:1248–1250.

4. Cho HS, Park YN, Lyu CJ, Park SM, Oh SH, Yang CH, et al. EBV-elicited familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Yonsei Med J. 1997. 38:245–248.

5. Horn M, Stutte HJ, Schlote W. Familial erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (Farquhar's disease): involvement of the central nervous system. Clin Neuropathol. 2002. 21:139–144.

6. Rostasy K, Kolb R, Pohl D, Mueller H, Fels C, Moers AV, et al. CNS disease as the main manifestation of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in two children. Neuropediatrics. 2004. 35:45–49.

7. Huddle DC, Rosenblum JD, Diamond CK. CT and MR findings in familial erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994. 162:1504–1505.

8. Kollias SS, Ball WS Jr, Tzika AA, Harris RE. Familial erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: neuroradiologic evaluation with pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1994. 192:743–754.

9. Fitzgerald NE, MacClain KL. Imaging characteristics of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2003. 33:392–401.

10. Takahashi S, Oki J, Miyamoto A, Koyano S, Ito K, Azuma H, et al. Encephalopathy associated with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis following rotavirus infection. Eur J Pediatr. 1999. 158:133–137.

11. Janka G, Imashuku S, Elinder G, Schneider M, Henter JI. Infection- and malignancy-associated hemophagocytic syndromes. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998. 12:435–444.

12. Henter JI, Nennesmo I. Neuropathologic findings and neurologic symptoms in twenty-three children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Pediatr. 1997. 130:358–365.

13. Imashuku S. Differential diagnosis of hemophagocytic syndrome: underlying disorders and selection of the most effective treatment. Int J Hematol. 1997. 66:135–151.

14. Akima M, Sumi SM. Neuropathology of familial erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: six cases and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1984. 15:161–168.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download