Abstract

The urachus is a fibrous cord that arises from the anterior bladder wall and extends cranially to the umbilicus. Traditionally, infection has been treated using a two-stage procedure that includes an initial incision and drainage which is then followed by elective excision. More recently, it has been suggested that a single-stage excision with improved antibiotics is a safe option. Thus, we intended to compare the effects of the two-stage procedure and the single-stage excision. We performed a retrospective review on nine patients treated between May 1990 and September 2005. The methods used in diagnosis were ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cystoscopy. The study group was comprised of three males and six females with a mean age of 28.2 years (with a range from three to 71 years). Symptoms consisted of abdominal pain, abdominal mass, fever, and dysuria. The primary incision and drainage followed by a urachal remnant excision with a bladder cuff excision (two-stage procedure) was performed in four patients. The mean postoperative hospitalization lasted 5.8 days (with a range of three to seven days), and there were no reported complications. A primary excision of the infected urachal cyst and bladder cuff (single-stage excision) was performed in the other five patients. These patients had a mean postoperative hospitalization time of 9.2 days (with a range of four to 15 days), and complications included an enterocutaneous fistula, which required additional operative treatment. The best method of treating an infected urachal cyst remains a matter of debate. However, based on our results, the two-stage procedure is associated with a shorter hospital stay and no complications. Thus, when infection is extensive and severe, we suggest that the two-stage procedure offers a more effective treatment option.

The urachus is a fibrous cord that arises from the anterior bladder wall and extends cranially to the umbilicus.1 Urachal cysts are rare anomalies that occur from the urachus. Most urachal cysts are not detected until adulthood, although they are detected rarely in asymptomatic children.2,3 A urachal cyst presents four anomalies: a patent urachus, a vesicourachal diverticulum, urachal cysts, and a urachal sinus.4-8

The treatment of urachal cysts involves primary excision of the cyst. However, the traditional treatment of an infected urachal cyst is composed of a two-stage approach, i.e., an incision and then drainage of the infected cyst followed by secondary excision.2-4 Recently, Newman et al.9 suggested that with the advent of improved antimicrobials and earlier detection, a single-stage procedure can be safely accomplished. However, studies which compared the two different treatments reported that single-stage excisions result in complications and longer postoperative hospitalizations, and that the two-stage procedure is complication-free.4,10 We conducted this study to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of both the single-stage excision and the two-stage procedure.

We performed a retrospective review of nine patients who had been diagnosed with an infected urachal cyst and who were treated at our institution from May 1990 to September 2005. We reviewed imaging studies, pathological specimens and hospital records, and checked patients' symptoms, diagnoses, treatments, and results. The study group was comprised of three males and six females, with a mean age of 28.2 years (with a range of three to 71 years). Laboratory studies included urinalysis, urine cultures, wound cultures, and blood cultures. Pyuria was defined as more than five white blood cells per high power field on urinalysis. The imaging studies used were ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fistulography, voiding cystourethrography and cystoscopy.

The single-stage excision involves a primary excision of the infected urachal cyst and bladder cuff, whereas the two-stage procedure involves a primary incision and drainage, a delay to ensure that the infection has cleared, and then a later excision of the urachal remnant and bladder cuff.

Of the nine patients, the most common symptom associated with an infected urachal cyst was abdominal pain (seen in eight cases); other symptoms included fever in six cases, dysuria in four patients, and umbilical discharge in one. In our study, seven infected urachal cysts were diagnosed in the nine patients by ultrasonography, which means the success rate of this diagnostic method was 77.8%. CT (four cases) and MRI (three cases) were used to determine the sizes of the infected urachal cysts, and fistulography (one case), voiding cystourethrography (one case) and cystoscopy (one case) were also performed (Table 1).

Four patients presented with pyuria by urinalysis, and E. coli was found by urine culture in one patient and by blood culture in another patient. Wound cultures discovered E. faecium in one patient and K. pneumonia in another patient (Table 2).

The primary excision of an infected urachal cyst and bladder cuff (single-stage excision) was performed in five patients. The mean number of postoperative hospitalization days was 9.2 (with a range of four to 15 days), and a complication was present in one patient: the patient developed an enterocutaneous fistula that required additional operative treatment (Table 3).

The two-stage procedure was performed in four patients. The interval of incision and drainage and secondary excision was 12.5 days (with a range of five to 14 days). The mean number of postoperative hospitalization days was 5.8 (with a range of three to seven), and there were no complications (Table 3) (Fig. 1, 2).

The optimal treatment method for infected urachal cysts remains a subject of debate. The present study shows that the two-stage procedure was complication-free (zero vs. one case) and involved a short postoperative hospitalization stay (5.8 vs. 9.2 days) compared with the single-stage excision. Although the introduction of improved antimicrobials and earlier detection by abdominal ultrasonography has improved the effectiveness of infected urachal cyst treatment, our results suggest that the two-stage procedure remains a more effective treatment option.

Newman et al.9 suggested that improved antimicrobials and earlier detection allow the single-stage excision to be accomplished safely, and that the risks of this procedure compare with those of complication development during the two admissions and two operations of the two-stage procedure. However, McCollum et al.10 performed five single-stage excisions and six two-stage procedures, and found that two of the five single-stage excision patients experienced complications, but that all two-stage procedure patients were complication-free. Similarly, Minevich et al.4 reported that three of nine single-stage excision patients had complications, but all patients who had the two-stage procedure had no complications at all. Moreover, they reported mean postoperative hospital stays of 14 and 11.5 days for the single-stage excision and the two-stage procedure, respectively.

An infected urachal cyst can cause abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness, fever, nausea, vomiting, dysuria, voiding difficulty, N. gonorrhea urethritis, epididymitis, and orchitis at presentation.11-13 In our study, patients presented with abdominal pain (eight cases), fever (six cases), voiding difficulty (four cases), an abdominal mass (three cases), and umbilical discharge (one case).

The luminal wall of a urachal cyst is composed of transitional epithelium, and infection may occur due to the accumulation of materials within the cyst.14 Infected urachal cysts can disseminate infection by hematogenous or lympatic spread or through direct invasion of the bladder and umbilicus.15 Newman et al.9 and MacMillian et al.16 reported that S. aureus is the most common bacteria found in cystic fluid, and that other bacteria found were aerobic or anaerobic, such as E. coli. In our study, E. faecium and K. pneumonia were also cultured, and E. coli was grown from both urine and blood cultures.

Allen et al.5 and Ozbek et al.11 suggested that ultrasonography is an ideal modality for diagnosing urachal cysts, since these entities are cystic, extraperitoneal, and are directly related to the bladder. Nagasaki et al.17 reported a 75% diagnostic success rate for ultrasound, whereas Minevich et al.4 reported 57.1% and Cilento et al.18 reported 100%. However, cases of concomitant abscess and cellulitis were misinterpreted by ultrasonography. During primary diagnosis, ultrasonography, CT and MRI were performed to determine the size of the cyst and also the relationship between the peripheral tissue and the cyst.17 In the presence of an umbilical discharge, fistulography was performed to confirm the existence of a fistula, voiding cystourethrography was performed for reflux,9 and cystography was also carried out to investigate bladder cancer. In our study, seven infected urachal cysts were diagnosed in the nine patients that underwent ultrasonography. CT and MRI were used to confirm the extent of infection.

In one of our nine cases, an extensive and severely infected urachal cyst was excised using the single-stage procedure, and an enterocutaneous fistula developed during the postoperative period and became operatively manageable. However, since the urachal cyst was extensive and severe, the two-stage procedure should have been considered.

The optimal treatment method for infected urachal cysts remains a subject of debate. Based on our results, the two-stage procedure produces a shorter postoperative hospital stay and no complications. However, in the case of small and localized infections, a single-stage excision can be considered in young adults without comorbidity. Thus, when evaluating complication frequencies alone, we determined that the two-stage procedure presents a more-effective treatment option.

Figures and Tables

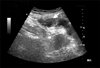

| Fig. 1Abdominal ultrasonographic finding of a urachal cyst (longitudinal view). A cystic lesion is shown on the dome area of the urinary bladder (arrow). |

References

1. Gearhart JP. Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editors. Exstrophy, epispadias, and other bladder anomalies. Campbell's Urology. 2002. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2136–2196.

2. Iuchtman M, Rahav S, Zer M, Mogilner J, Siplovich L. Management of urachal anomalies in children and adults. Urology. 1993. 42:426–430.

3. Mesrobian HG, Zacharias A, Balcom AH, Cohen RD. Ten years of experience with isolated urachal anomalies in children. J Urol. 1997. 158(3 Pt 2):1316–1318.

4. Minevich E, Wacksman J, Lewis AG, Bukowski TP, Sheldon CA. The infected urachal cyst: primary excision versus a staged approach. J Urol. 1997. 157:1869–1872.

5. Allen JW, Song J, Velcek FT. Acute presentation of infected urachal cysts: case report and review of diagnosis and therapeutic interventions. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004. 20:108–111.

6. Nirasawa Y, Ito Y, Tanaka H, Seki N. Urachal cyst associated with a suprapubic sinus. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999. 15:275–276.

7. Bauer SB, Retik AB. Urachal anomalies and related umbilical disorders. Urol Clin North Am. 1978. 5:195–211.

8. Blichert-Toft M, Nielsen OV. Congenital patent urachus and acquired variants. Diagnosis and treatment. Review of the literature and report of five cases. Acta Chir Scand. 1971. 137:807–814.

9. Newman BM, Karp MP, Jeweet TC, Cooney DR. Advances in the management of infected urachal cysts. J Pediatr Surg. 1986. 21:1051–1054.

10. McCollum MO, Macneily AE, Blair GK. Surgical implications of urachal remnants: Presentation and management. J Pediatr Surg. 2003. 38:798–803.

11. Ozbek SS, Pourbagher MA, Pourbagher A. Urachal remnants in asymptomatic children: gray-scale and color Doppler sonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001. 29:218–222.

12. Kojima Y, Miyake O, Taniwaki H, Morimoto A, Takahashi S, Fujiwara I. Infected urachal cyst ruptured during medical palliation. Int J Urol. 2003. 10:174–176.

13. Campanale RP, Krumbach RW. Intraperitoneal perforation of infected urachal cyst. Am J Surg. 1955. 90:143–145.

14. Goldman IL, Caldamone AA, Gauderer M, Hampel N, Wesselhoeft CW, Elder JS. Infected urachal cysts: a review of 10 cases. J Urol. 1988. 140:375–378.

15. Borten M, Friedman EA. Spontaneous prevesical (Retzius-space) abscess with extraperitoneal presacral dissemination. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1984. 29:841–844.

16. MacMillan RW, Schullinger JN, Santulli TV. Pyourachus: an unusual surgical problem. J Pediatr Surg. 1973. 8:387–389.

17. Nagasaki A, Handa N, Kawanami T. Diagnosis of urachal anomalies in infancy and childhood by contrast fistulography, ultrasound and CT. Pediatr Radiol. 1991. 21:321–323.

18. Cilento BG Jr, Bauer SB, Retik AB, Peters CA, Atala A. Urachal anomalies: defining the best diagnostic modality. Urology. 1998. 52:120–122.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download