Abstract

To report a non-fatal case of reperfusion pulmonary edema (RPE) after the removal of a hepatocellular carcinoma embolus, which had caused an acute obstruction of the tricuspid valve and pulmonary vasculature during a hepatic lobectomy. Pulmonary embolism caused by hepatocellular carcinoma embolus is extremely rare, and, in the present case, it was associated with unusual clinical features. A 69-year-old ASA II woman with hepatocellular carcinoma was presented for an elective left hepatic lobectomy. During the surgery, the tumor embolus was dislodged from the interior of the lumen of the inferior vena cava (IVC), which then drifted into the tricuspid valve area and pulmonary vasculature. The patient showed the specific signs of acute pulmonary embolism, such as a reduction in end-tidal carbon dioxide, an increase in central venous pressure, and a decrease in arterial pressure. The patient exhibited the symptoms for about 10 minutes. After this period, however, cardiovascular variables became relatively stable, even during a mechanical obstruction due to cross-clamping the pulmonary artery for embolectomy. After several hours of pulmonary embolectomy, the patient experienced an episode of RPE. The ventilatory supports for the treatment of RPE were successful, and the patient recovered without any complications. The patient's case in the present study demonstrates that pulmonary embolism may occur as a result of a hepatocellular carcinoma extending into the IVC during operative management. The anesthesiologist should be careful of the possibilities of RPE after removal of the tumor embolus.

Prolonged periods of pulmonary artery occlusion followed by reperfusion can cause pulmonary edema. The edema is likely to occur due to an increase in pulmonary vascular permeability occurring during the reperfusion phase, rather than the result of increased capillary hydrostatic pressure. Horgan et al. have demonstrated in animal models that pulmonary edema can occur after a 24-hour period of occlusion of the pulmonary artery, followed by a 2-hour period of reperfusion.1 Human data on reperfusion edema occurring after release of pulmonary occlusion by tumor embolus are unavailable. In the present study we report a patient's case with successful recovery from reperfusion pulmonary edema (RPE), which occurred after delayed removal of a pulmonary embolus. The embolus originated from hepatocellular carcinoma that extended into the inferior vena cava (IVC) during hepatic lobectomy.

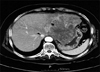

A 69-year-old, weighing 60 kg, with ASA physical status II, was presented to the general surgery department for a left hepatic lobectomy, as a treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a probable huge malignant tumor in the left hepatic lobe, and a low density lesion in the lumen of IVC, suggesting that the tumor had extended into the IVC (Fig. 1).

We prepared for emergency institution of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in the operating room. The patient was monitored by ECG, pulse oximetry, arterial and central venous pressure (CVP), and end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) monitoring. Initial vital signs included: blood pressure, 140/80 mmHg; heart rate, 75 beats · min-1; and arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2), 100% after preoxygenation. Intravenous sedation was started with 2 mg of midazolam and 50 µg of fentanyl. The patient underwent anesthetic induction and tracheal intubation with 200 mg of thiopental and 60 mg of succinylcholine. Muscle relaxation was induced with 6 mg of vecuronium, and general anesthesia was maintained by administering 1.0-1.5% of isoflurane plus 60% nitrous oxide. Controlled ventilation was conducted with a tidal volume of 600 mL, I : E ratio at 1 : 2, and a respiratory rate of 9/min to 11/min.

After two and a half hours of starting the surgery, CVP suddenly increased, from 8-10 to 16-21 mmHg. The patient became hypotensive, with a systolic blood pressure of 80 mmHg, and SpO2 fell from 100 to 90%. Heart rate increased moderately, from 80 to 95 beats · min-1, and the patient's EtCO2 level showed a marked reduction, from 38 to 25 mmHg. At this point, diastolic murmur could be detected at the tricuspid area. It was presumed that the tumor embolus was dislodged from interior of the lumen of the IVC, and then had floated into the tricuspid valve area. Nitroglycerin (0.5-10 µg · kg-1 · min-1) and dopamine (3-10 µg · kg-1 · min-1) were used to reduce preload and increase contractility. The cardiac surgeon was summoned to open the heart. During the preparation for transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and CPB, the CVP returned back to normalcy suddenly after 10 minutes of the initial event. At this point, the patient's hemodynamic variables were stable, with blood pressure of 125/74 mmHg, and heart rate of 82 beats · min-1. The SpO2 and EtCO2 levels also returned to normalcy. Simultaneously, TEE was performed to search the tumor embolus in the right heart, but was not traceable in the right heart chamber. The patient remained hemodynamically stable until the end of the left hepatic lobectomy. We were unable to ascertain the exact location of the embolus, but we could surmise that it had moved from the tricuspid valve area into the main pulmonary artery. The decision was made to perform a pulmonary embolectomy after verifying the exact location of the tumor embolus.

CT, performed one day after the left hepatic lobectomy, showed a large filling defect in the left pulmonary interlobar artery (Fig. 2). Pulmonary angiographic findings (Fig. 3) were consistent with those of the chest CT. Atrial fibrillation appeared after pulmonary arterial catheterization for the angiogram, and was treated successfully by digitalization. Echocardiography was negative for the detection of the tumor embolus and myocardial ischemia by wall motion criteria, but showed mild tricuspid and aortic valve regurgitations.

Six days later, the patient was shifted to the operating room for pulmonary embolectomy. The trachea was intubated with a double-lumened endobronchial tube for one-lung ventilation. Despite three repeated cross-clampings and unclampings of the left pulmonary artery for extraction of the pulmonary embolus, no remarkable changes in hemodynamic variables were noted, including CVP, EtCO2 and SpO2. The only change noted was a short period of atrial fibrillation, as visualized by ECG. The extracted pulmonary embolus was diagnosed pathologically as a hepatocellular carcinoma (Fig. 4).

The patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit as, intubated and ventilatory support was applied with synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV), and 10 mmHg of pressure support mode. By the 10th postoperative hour, chest radiographs revealed moderate pulmonary edema (Fig. 5). Ventilator mode was shifted into pressure-controlled mode. Additional positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) therapy was started. An improvement in PaO2 with mechanical ventilation was observed. About 42 hours later, chest radiographs showed regression of the pulmonary edema, and extubation was carried out without any difficulties. The patient recovered slowly, and was discharged from the hospital 38 days after her initial admission.

Patients with a tumor embolus in the IVC have a great risk of pulmonary embolism2,3 and obstructions of the tricuspid valve4 during operative management. Hospital mortality rate caused by clinically-apparent pulmonary embolism is 30% for untreated patients, and around 2.5% for those receiving up-to-date treatment.5

The tumor embolus in this patient's IVC was suspected preoperatively, by virtue of preoperative abdominal CT findings. We are thankful to this preoperative information, as we could predict, to some extent, that the predominant symptoms in our patient-including hypotension followed by a decrease in SpO2 and a sudden increase in CVP during the hepatic lobectomy - were due to the migration of the tumor embolus into the right side of the heart. Perhaps the use of TEE should have been considered in advance before the start of surgery, because TEE has been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of tricuspid valve obstructions and pulmonary emboli.6,7

Classic signs of pulmonary embolism, including tachypnea, tachycardia, hypocarbia, and a normal or high arterial pH value, may be absent in the anesthetized, mechanically ventilated patient.8 Migration of the tumor embolus, and partial but not massive obstructions of the pulmonary artery may explain the absence of these classic signs. In the present case, the CVP returned to normalcy about 10 minutes after the initial event, and the vital signs remained stable, with no decrease in EtCO2 over the next several hours until the end of the left hepatic lobectomy. We attributed this to the drifting of the tumor embolus into the main pulmonary artery, and the partial closure of the pulmonary artery. The hemodynamic variables after the end of left hepatic lobectomy also remained stable, and changes in EtCO2 and SpO2 as a result of low cardiac output states due to pulmonary embolism or right heart failure were unlikely in this patient.

Though embolus size is important in determining the outcome of pulmonary emboli; mechanical obstruction alone can not explain the events occurring in association with an acute pulmonary embolism.9 Several studies have shown that there is little, or no, correlation between the degree of mechanical obstruction and the hemodynamic manifestations of pulmonary embolism.10,11 Neural and humoral stimuli are important co-determinants of the severity of hemodynamic disturbance in acute pulmonary embolism. Once a thrombus lodges in a pulmonary artery, a rapid and complex interaction of cellular and molecular events occur, resulting in the release of procoagulants and vasoconstrictors, plus anticoagulants and vasodilators. It seems likely that the body's ability to balance these opposing responses determines the outcome of the treatment.12 The absence of acute right-sided heart failure due to increased pulmonary vascular resistance in this patient illustrated that neither pulmonary obstruction nor vasoconstriction contributed significantly to pulmonary hypertension. Even during a surgical procedure, mechanical obstruction, accompanied by cross-clamping the left pulmonary artery, caused no remarkable change in CVP, and in this case, did not result in right-sided heart failure.

RPE was diagnosed on the basis of chest radiographs taken during the immediate postoperative period in the Intensive Care Unit. Although restoration of blood flow to an ischemic organ is essential to prevent irreversible cellular injury, reperfusion per se may augment tissue injury, perhaps doing far greater damage than ischemia alone. RPE is a common consequence of pulmonary thromboendarterectomy, and often requires prolonged mechanical ventilation and increased inspired oxygen concentrations ranging from days to weeks after surgery.13 In this patient, a pressure- controlled strategy, with peak airway pressure as low as possible and optimal PEEP, was selected for postoperative mechanical ventilation in the treatment of RPE. The patient remained in the Intensive Care Unit for 5 days after the pulmonary embolectomy, and recovered without any neurological deficits, or any other adverse effects.

In conclusion, obstruction of the tricuspid valve and pulmonary embolism may occur during surgical treatment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma extending into the IVC, because the hemodynamics are usually unstable and the IVC is manipulated intraoperatively. Signs of pulmonary embolism may take different forms, such as stable hemodynamics, with no remarkable changes in EtCO2 and SpO2. The anesthesiologist must be vigilant for such unusual presentations of pulmonary embolism. Early diagnosis of pulmonary embolism by close monitoring and institution of aggressive treatments will help to avoid fatal consequences in such cases.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen showing a huge tumor in the left hepatic lobe (arrow) and thrombosis in the lumen of inferior vena cava (arrowhead). |

| Fig. 2Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest showing a large filling defect in the left pulmonary interlobar artery. Arrowhead indicates the pulmonary embolus. |

| Fig. 3Pulmonary angiography showing a large filling defect in the left interlobar artery (arrowheads), which demonstrates the presence of pulmonary embolism. |

References

1. Horgan MJ, Lum H, Malik AB. Pulmonary edema after pulmonary artery occlusion and reperfusion. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989. 140:1421–1428.

2. Milne B, Cervenko FW, Morales A, Salerno TA. Massive intraoperative pulmonary tumor embolus from renal cell carcinoma. Anesthesiology. 1981. 54:253–255.

3. Wilkinson CJ, Kimovec MA, Uejima T. Cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with malignant renal neoplasms. Br J Anaesth. 1986. 58:461–465.

4. Utley JR, Mobin-Uddin K, Segnitz RH, Belin RP, Utley JF. Acute obstruction of tricuspid valve by Wilm's tumor. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1973. 66:626–628.

5. Carson JL, Kelley MA, Duff A, Weg JG, Fulkerson WJ, Palevsky HI, et al. The clinical course of pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 1992. 326:1240–1245.

6. Sasaoka N, Kawaguchi M, Sha K, Sakamoto T, Shimokawa M, Kitaguchi K, et al. Intraoperative immediate diagnosis of acute obstruction of tricuspid valve and pulmonary embolism due to renal cell carcinoma with transesophageal echocardiography. Anesthesiology. 1997. 87:998–1001.

7. Yamashita C, Azami T, Okada M, Toyoda Y, Wakiyama H, Yoshida M, et al. Usefulness of cardiopulmonary bypass in reconstruction of inferior vena cava occupied by renal cell carcinoma tumor thrombus. Angiology. 1999. 50:47–53.

8. Capan LM, Miller SM. Monitoring for suspected pulmonary embolism. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2001. 19:673–703.

9. Wood KE. Major pulmonary embolism: review of a pathophysiologic approach to the golden hour of hemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2002. 121:877–905.

10. Sharma GV, McIntyre KM, Sharma S, Sasahara AA. Clinical and hemodynamic correlates in pulmonary embolism. Clin Chest Med. 1984. 5:421–437.

11. Miller RL, Das S, Anandarangam T, Leibowitz DW, Alderson PO, Thomashow B, et al. Association between right ventricular function and perfusion abnormalities in hemodynamically stable patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 1998. 113:665–670.

12. Stratmann G, Gregory GA. Neurogenic and humoral vasoconstriction in acute pulmonary thromboembolism. Anesth Analg. 2003. 97:341–354.

13. Levinson RM, Shure D, Moser KM. Reperfusion pulmonary edema after pulmonary artery thromboendarterectomy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986. 134:1241–1245.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download