Abstract

There are many medical causes of abdominal pain; abdominal epilepsy is one of the rarer causes. It is a form of temporal lobe epilepsy presenting with abdominal aura. Temporal lobe epilepsy is often idiopathic, however it may be associated with mesial temporal lobe sclerosis, dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors and other benign tumors, arterio-venous malformations, gliomas, neuronal migration defects or gliotic damage as a result of encephalitis. When associated with anatomical abnormality, abdominal epilepsy is difficult to control with medication alone. In such cases, appropriate neurosurgery can provide a cure or, at least, make this condition easier to treat with medication.

Once all known intra-abdominal causes have been ruled out, many cases of abdominal pain are dubbed as functional. If clinicians are not aware of abdominal epilepsy, this diagnosis is easily missed, resulting in inappropriate treatment. We present a case report of a middle aged woman presenting with abdominal pain and episodes of unconsciousness. On evaluation she was found to have an intra-abdominal foreign body (needle). Nevertheless, the presence of this entity was insufficient to explain her episodes of unconsciousness. On detailed analysis of her medical history and after appropriate investigations, she was diagnosed with temporal lobe epilepsy which was treated with appropriate medications, and which resulted in her pain being relieved.

Epilepsy presenting with abdominal aura is known as abdominal epilepsy. It is now considered as a definite clinical entity.1 In the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification, it is considered to be part of a simple or complex partial seizure, and is not listed as a separate entity. However, in the Semiological seizure classification,2 abdominal epilepsy, which is epilepsy presenting with abdominal or epigastric aura, is assigned to a separate category, because of its particular nature and common occurrence in cases of temporal lobe epilepsy.

In this study, we present a case report of a middle aged female patient, who is a tailor by occupation, and who was suffering from repeated episodes of abdominal pain, vomiting and fainting attacks. On evaluation, she was found to have a needle in the abdomen. However, this finding alone was insufficient to explain all of her symptoms. On further evaluation, she was found to have abdominal epilepsy.

A 38-year-old woman presented to the department of general surgery, Kasturba Medical College Hospital, Manipal, on 15th may 2002, complaining of repeated episodes of abdominal pain, vomiting and loss of consciousness for the past 2 years. She was a tailor by profession.

She had first suffered from an attack of severe abdominal pain 2 years previously, while standing in the bus terminus. Shortly afterwards, she vomited and fell down unconscious and remained so for 2 to 5 minutes. On regaining consciousness, she could not recollect the details of the episode. Medical help was sought but no alleviation was found for her symptoms. She had 6 such episodes over a period of 2 years. The last episode occurred 15 days prior to her hospitalization at our institution. Her abdominal pain was spasmodic and localized to the umbilical area and the lower abdomen. It was mild to moderate in intensity. However, she occasionally experienced severe pain in the epigastric region, associated with vomiting and a peculiar sensation which permeated throughout the same area. This was invariably followed by loss of consciousness for 2 to 5 minutes. After regaining consciousness, she could not recollect ictal events. During such episodes, she experienced neither incontinence of the bowel or bladder, nor generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Post ictal automatism was absent. Patient initially was not aware of the importance of the epigastric pain. Soon she understood the sequence of events and was able to avoid falling down.

In 1990, she was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and treated with a standard course of drugs for 6 months. She is married with two children. Both were normal vaginal deliveries. After the birth of her second child, she underwent post-partum sterilization in 1991. There was no other significant medical history.

On examination, she was found to be moderately built and moderately well nourished. Abdominal examination did not reveal any abnormality. The examination of the central nervous system was also normal. All other examinations were also within normal limits.

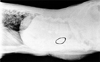

Hemogram was normal. ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate) was 14 mm at the end of the first hour. Urine microscopy showed 2 - 4 WBC/hpf, and 0-1 RBC/hpf. Urine culture showed the presence of E-coli 105 cfu/mL. The ultrasound examination of the abdomen, kidney, ureter and bladder was normal. Blood, renal and liver functions were normal. Serum amylase and lipase were within normal limits. Screening for porphyria was done and it was also normal. In view of the presence of RBCs in the urine and spasmodic pain in the abdomen (in spite of the ultrasound examination of the abdomen being normal), she underwent an intravenous urogram. It was normal, but incidentally a needle was found in her abdomen at the L3 level on the left side (Fig. 1 and 2). However, this finding alone could not explain her fainting attacks. Psychiatric evaluation did not reveal any functional abnormality. She was further evaluated with a CT scan of the brain and EEG (Electro Encephalo Gram). The CT scan of the brain was normal. The EEG revealed the presence of right fronto-temporal sharp waves with secondary generalized spike wave discharges, especially precipitated by hyperventilation. She was prescribed 300 mg eptoin tablets, to be taken at night. The patient willfully expressed the desire to have the foreign body removed, in spite of our telling her that it might not be the cause of her abdominal pain. Laparotomy was done 15 days later and the needle was recovered from the root of the transverse mesocolon on the left side. It was brittle and it broke while we were trying to remove it (Fig. 3). The postoperative period was uneventful. Eptoin administration was continued. She is currently being followed-up. To date, she has not suffered from any further episodes.

Typical complex partial seizures of temporal lobe origin have three primary components: aura, absence and automatism. Aura can occur as an initial manifestation of a complex partial seizure, or in isolation as a simple partial seizure. It typically comprises visceral, cephalic, gustatory, dysmnestic or affective symptoms. A rising epigastric sensation is the most common symptom. Motor arrest or absence is a prominent symptom, especially in the early stages of seizures arising in the mesial temporal structures. There is frequent dystonic posturing or spasm of the arm which is contralateral to the seizure discharge, and this is a useful lateralizing sign. The automatisms of the mesiobasal temporal lobe seizures are typically less violent and are usually oro-alimentary (lip-smacking, chewing, swallowing) or gestural (fumbling, fidgeting, repetitive motor actions, undressing, sexually directed actions, walking, running) and are sometimes prolonged.

Post ictal confusion and headache are common after a temporal lobe complex partial seizure. Amnesia is frequently associated with absence and automatism. Secondary generalization is much less common.

Once all of the known intra-abdominal causes have been ruled out, many cases of abdominal pain, are designated as functional. If clinicians are not aware of abdominal epilepsy, the diagnosis is easily missed, resulting in inappropriate treatment. In our case, even though, coincidentally, a needle was found inside the abdomen, the patient's symptoms could not be satisfactorily explained. This case beautifully illustrates how a detailed medical history examination, careful analysis of the symptoms, and appropriate investigation helps in determining the proper diagnosis and treatment.

The most common pathology underlying this type of epilepsy is hippocampal sclerosis. This is characteristically associated with a history of febrile convulsions and the subsequent development of complex partial seizure in late childhood or adolescence. Other etiologies include dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors and other benign tumors, arteriovenous malformations, gliomas, neuronal migration defects or gliotic damage as a result of encephalitis.

In cases of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, EEG often shows anterior or mid temporal spikes. Superficial or deep sphenoidal electrodes can assist in the detection of this disorder in some cases. Other changes include intermittent or persisting slow activity over the temporal lobes, which can be unilateral or bilateral.3

In our case, the needle in the abdomen could have been swallowed accidentally, entered the abdominal cavity inadvertently if she had fallen on it during an episode of fit, or been left behind during postpartum sterilization surgery. The needle had disintegrated and was brittle. We were not able to recover it in a single piece. It was difficult to say if it was a sewing needle or one used by surgeons.

Very little experimental work has been done to study the reaction of the peritoneum in response to iatrogenically introduced foreign bodies. Published clinical series are limited, perhaps due to legal implications. In practice one has to count on the personal experience of the surgeons when faced with such a situation. An experimental study done on street dogs by K. K. Dangayach et al.4 showed that sponge or swab-like foreign bodies are more harmful than smooth metallic ones. Morbidity and mortality were also high in the case of swabs/gauze pieces. A review of the literature revealed that various types of iatrogenic foreign bodies, such as gauze pieces, artery forceps, needles, retractors, towel clips, glass tubes and rods, small glass bottles, metallic clips (used in laparoscopic cholecystectomy), ventriculoperitoneal shunt tubes, and migrated IUCD devices have been found. Inert foreign bodies generally produce no symptoms; indeed, a few cases were detected 20 years later.5 Foreign bodies that are infected and those that are rough and reactive tend to be detected early on. There is no uniform consensus on the management of asymptomatic intra-abdominal foreign bodies. However, the general opinion is that all intra-abdominal foreign bodies, once diagnosed, should be removed at the earliest possible opportunity.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Agrawal P, Dhar NK, Bhatia MS, Malik SC. Abdominal epilepsy. Indian J Pediatr. 1989. 56:539–541.

2. Benbadis SR. Wyllie E, editor. Epileptic seizures and syndromes. Neurologic Clinics. 2001. Philadelphia: Saunders;254–255.

3. Shorvon SD. Hand book of epilepsy treatment. 2000. Oxford: Blackwell Science;12.

4. Dangayach KK, Gupta OP, Bhargava SK, Udavat M, Singh H. Surgical complications of left over intraperitoneal foreign body. Ind J Surg. 1984. 46:84–87.

5. Dukalska D, Stankowski A, Gurda L, Zabska G. 20-year presence of a foreign body in the retroperitoneal space. Wiad Lek. 1987. 40:901–903.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download