Abstract

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a common disease with a high mortality rate due to right ventricular dysfunction and underfilling of the left ventricle. We present a case of a 33-year-old man with hemodynamically compromised massive PE. His left atrium was collapsed with marked dilatation of the right atrium and ventricle on multi-detector-row CT scans. The patient was treated with an intracatheter injection of a mutant tissue-type plasminogen activator and subsequently showed clinical and radiological improvements. The small left atrial size in combination with a right ventricular pressure overload was considered to be an adjunctive sign of hemodynamically compromised massive PE.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is frequently encountered not only in the hospital setting, but as well in private clinical practice. Because untreated PE is associated with an increased mortality risk, accurate and prompt diagnosis is of critical importance.1,2 A multi-detector-row CT (MDCT) scan provides information about pulmonary arteries, the morphology of heart chambers, and the volume assessment obtained during a single breath hold.3-5 We present MDCT findings of hemodynamically compromised massive pulmonary embolism and emphasize the clinical significance of a small left atrium.

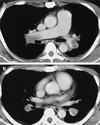

A 33-year-old man was referred to our institution with a 2-day history of dyspnea at rest and syncope. His past history and family history were not remarkable except that he had made two long-distance trips 1 month previously. His physical examination was remarkable for tachycardia (114 beats per minute) and tachypnea (30 breaths per minute). He was obese with a body mass index of 30.4 (body weight: 90 kg, height: 172 cm). The blood pressure was 116/60 mmHg, and the oxygen saturation decreased to 85% on room air. A laboratory examination showed a D-dimer level of 8.7 µg/mL (normal, < 1.0 µg/mL), a fibrinogen degradation product of 41 µg/mL (normal, < 5.0 µg/mL), and a C-reactive protein level of 2.2 mg/dL (normal, < 0.3 mg/dL). The electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated sinus tachycardia and an SI, QIII, TIII pattern (Fig. 1) suggestive of pulmonary embolism. Chest radiography demonstrated prominent bilateral central pulmonary arteries. Echocardiography showed a small left atrium (left atrial diameter, 26 mm) with marked dilatation of the right atrium (Fig. 2). The left ventricular end- diastolic volume was 85 mL and the end-systolic volume was 22 mL. That is, the left ventricular stroke volume was 63 mL and the cardiac index was 3.5 L/min/m2. Contrast-enhanced CT scans using a 4-slice MDCT scanner (Aquillion, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) demonstrated large clots in the pulmonary arteries (Fig. 3). The right atrium and right ventricle were dilated, but a marked diastolic collapse of the left atrium was noted (Fig. 4).

To measure the volumes of the right and left atria precisely, each atrial volume was calculated by encircling the region of interest at the workstation (Fiji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), multiplying each area by its slice thickness (8 mm) and adding the results together (Fig. 4). The right atrial volume was 124 mL (Normal: 110-185 mL), but the left atrial volume markedly decreased to 53 mL (Normal: 100-130 mL).6 Based on the findings of the ECG, the echocardiogram, and CT, a diagnosis of massive pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic compromise was made. Magnetic resonance venography revealed a deep vein thrombosis in the left popliteal vein. An inferior vena cava filter (TrapEase; Cordis, Miami, FL, USA) was placed via the right superficial femoral vein to prevent further thromboembolism. Intravenous digital subtraction angiography demonstrated intraluminal filling defects in both of the central pulmonary arteries. The pulmonary artery pressure was 58 mmHg. The mutant tissue-type plasminogen activator, monteplase (Cleactor, Eisai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (1,600,000U), diluted in normal saline (20 mL), was administered directly into the pulmonary trunk using a 4-French catheter. Anticoagulation therapy consisted of the administration of intravenous heparin (120,000 U/day) followed by oral warfarin (4 mg/day). The target international normalized ratio (INR) was 2.0. Two weeks after the initiation of the anticoagulation therapy, the patient's dyspnea was alleviated and the oxygen saturation increased to 98% on room air. The patient had an uneventful posttreatment course and was discharged 3 weeks after the referral.

Follow-up CT scans demonstrated that the large emboli were dissolved almost completely and the sizes of the right and left atria were normalized. The right atrial volume became 115 cm3 and the left atrial volume became 111 cm3. He appeared well and stable during the 10 months of follow-up.

The mortality of PE is usually due to circulatory failure from right heart failure (acute cor pulmonale).7 Although life-threatening PE traditionally has been equated with anatomically massive PE (defined as a> 50% obstruction of the pulmonary vasculature or the occlusion of two or more lobar arteries), it has been considered that the outcome from PE is a function of both the size of the embolus and the underlying cardiopulmonary function.8 A pressure overload of the right ventricle secondary to pulmonary arterial hypertension initially results in right ventricular dysfunction, which may progress to right ventricular failure and circulatory collapse. A sudden increase in the right ventricular afterload results in elevated right ventricular wall tension, right ventricular dilatation, and eventually right ventricular dysfunction. Dilatation of the right ventricle causes the interventricular septum to shift towards the left ventricle and results in a decreased left ventricular diastolic volume. Right ventricular contractile dysfunction and tricuspid regurgitation due to the elevated pressures within the right ventricle cause a decreased output from the right ventricle, also contributing to underfilling of the left ventricle. Underfilling of the left ventricle results in decreased cardiac output, and, if severe, decreased systemic blood pressure and perfusion.7-10 In such a hemodynamically compromised state, the left atrial cavity is decreased in size. CT can precisely assess both the size of the embolus and the underlying cardiovascular function.7-10 Some investigators suggested that the severity of PE can be quantitatively assessed with CT. Right ventricular dilatation, and straitening of the interventricular septum or the septum toward the left ventricle may be seen, indicating hemodynamic compromise.7-10 A small left atrium is a general manifestation of a decreased pulmonary venous return and not a specific finding of PE. However, to our knowledge, no previous report describes the clinical significance of a small left atrium or atrial septal bowing toward the left atrium11.

Echocardiography is an operator/patient-dependent modality and certain patient characteristics such as obesity and respiratory distress may not permit an optimal study.7 However, MDCT can clearly depict clots within the pulmonary artery as well as cardiac anatomy, allowing for an evaluation of the size of the ventricular and atrial cavities as well as the position of each septum.12 The quantitative measurements of each chamber volume are easily obtained when using the picture archiving and communication system and a computer workstation.13 At present, there is no consensus on the optimal strategy for diagnosing acute PE with hemodynamic compromise. This paper suggested the usefulness of MDCT for the evaluation of hemodynamically compromised PE and it emphasized the clinical importance of a small left atrium in such a state.

In conclusion, a single case cannot be generalized to others without additional scientific verifications. However, a small left atrial size in combination with a right ventricular pressure overload seems to be an adjunctive sign of hemodynamically compromised massive PE.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Apical four-chamber view of the echocardiogram demonstrated marked dilatation of the right ventricle and right atrium. The interventricular septum and the atrial septum were deviated towards the left ventricle and left atrium respectively. RV, right ventricle; RA, right atrium; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium. |

| Fig. 3A. Contrast-enhanced CT performed at the level of the right main pulmonary artery showed a large emboli in the bilateral main pulmonary arteries. B. Contrast-enhanced CT performed at the level of the descending interlobar pulmonary arteries showed low-attenuation emboli outlined by high attenuation contrast-enhanced flowing blood. |

| Fig. 4Contrast-enhanced CT at the mid-ventricular level showed that the interventricular septum was straightened and the right ventricle and right atrium were dilated, indicating a raised pressure on the right side of the heart. The left atrium was markedly decreased in size, indicating underfilling of the left side of the heart. The region of interest was determined using contrast-enhanced CT scans. Each area (1 = right atrium; 2 = left atrium) was multiplied by its slice thickness (8 mm) and the results were added together using the workstation (Fiji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). |

References

1. Dalen JE, Alpert JS. Natural history of pulmonary embolism. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1975. 17:257–270.

2. Barritt DW, Jordan SC. Anticoagulant drugs in the treatment of pulmonary embolism. A controlled trial. Lancet. 1960. 1:1309–1312.

3. De Monye W, Pattynama PMT. Contrast-enhanced spiral computed tomography of the pulmonary arteries; an overview. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001. 7:33–39.

4. Van Strijen MJ, de Monye W, Kieft GJ, Pattynama PM, Huisman MV, Smith SJ, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with spiral CT as a second procedure following scintigraphy. Eur Radiol. 2003. 13:1501–1507.

5. Blachere H, Latrabe V, Montaudon M, Valli N, Couffinhal T, Raherisson C, et al. Pulmonary embolism revealed on helical CT angiography: comparison with ventilation-perfusion radionuclide lung scanning. Am J Roentgenol. 2000. 174:1041–1047.

6. Hirasawa K, Okamoto M. Cardiovascular anatomy. Buntankaibougaku. 1982. Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara & Co., Ltd.;6–17. (in Japanese).

7. Contractor S, Maldjian PD, Sharma VK, Gor DM. Role of helical CT in detecting right ventricular dysfunction secondary to acute pulmonary embolism. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002. 26:587–591.

8. Wood KE. Major pulmonary embolism: review of a pathophysiologic approach to the golden hour of hemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2002. 21:877–905.

9. Hiorns MP, Mayo JR. Spiral computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2002. 53:258–268.

10. Mastora I, Remy-Jardin M, Masson P, Galland E, Delannoy V, Bauchart JJ, et al. Severity of acute pulmonary embolism: evaluation of a new spiral CT angiographic score in correlation with echocardiographic data. Eur Radiol. 2003. 13:29–35.

11. Rosenquist GC, Kelly JL, Chandra R, Ruckman RN, Galioto FM Jr, Midgley FM, et al. Small left atrium and change in contour of the ventricular septum in total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: a morphometric analysis of 22 infant hearts. Am J Cardiol. 1985. 55:777–782.

12. Hofmann LK, Becker CR, Flohr T, Schoepf UJ. Multidetector-row CT of the heart. Semin Roentgenol. 2003. 38:135–145.

13. Hama Y, Kusano S. Picture archiving and communication system: prospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2002. 8:21–25.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download